Philippine Defense Today (Adroth.ph)

In Defense of the Republic of the PhilippinesIn light of the increasing number of concerned Filipinos organizing themselves for expeditions to the Municipality of Kalayaan, the original “Traveling to Pag-asa” article (available here) has been updated to incorporate fresh information. It includes an updated travel planning flowchart, updates on private initiatives to reach the islands, as well as a few minor edits.

How far away is it?

At over 300 kilometers west of Palawan, the islands of the Municipality of Kalayaan are among the most remote communities in the Republic of the Philippines. In terms of distance from major population centers, it is in the same league as Basco in Batanes, Mapun (formerly Cagayan de Sulu) and Bongao in Tawi-Tawi. What sets this municipality apart, however, are the a unique combination of barriers-to-access that have greatly retarded its development. This article explores those challenges.

Travel period

Travel to the island is only advisable within a narrow window each year. As per reports from the office of the municipal mayor, the interval between April of May presents the best weather conditions for both sea and air travel. As will be described later in this article, optimal sea conditions are essential for travel by boat.

While weather information specifically for Pag-asa is unavailable on various online weather Websites, Weather.com publishes weather information for nearby Song Tu Tay island — formerly Pugad Island.

http://www.weather.com/weather/5-day/Song+Tu+Tay+South+West+Cay+VMXX0030:1:VM

Travel by air

From the air, Pag-asa’s defining feature is its 1.3 kilometer runway: Rancudo airfield. It is an unpaved coral airstrip, covered for the most part, by grass, named after a forward-thinking Commanding General of the Philippine Air Force who had it constructed in the early 70s.

|

As per a Memorandum of Agreement between the Armed Force of the Philippines and the Municipality of Kalayaan, signed in October 5, 2005, the airfield is open for joint civilian and military use. However, no regular commercial flights visit the island.

|

|

To date, Rancudo does not appear on the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines’ (CAAP) official list of airports and has not been rated as a civilian aerodrome. The latter reportedly presents aircraft charter companies with potential aircraft insurance issues, thus serving as a deterrent to service. As per the above agreement, responsibility for having Rancudo rated as an aerodrome rests with the municipality — whose attempts to initiate the rating process, thus far, have been unsuccessful. Rejuvenated efforts to pursue certification are currently underway by way of the KIG development forum FB group and on Timawa.net

Despite the lack of a civilian rating, on July 20, 2011, a Dornier DO-228 became one of the first chartered commercial flights to land on Pag-asa island. The passengers (which consisted of a congressional delegation and other government dignitaries) chartered the plane at a cost of PhP65,000 per flying-hour and PhP7,000 per hour on stand-by time, for a total price tag of P1.8M. The rates quoted were a function of the aircraft type and cheaper alternatives would have reportedly been available. The impact of the unrated airstrip on overall cost is unclear at this point.

Travel time to Pag-asa by air is approximately two to three hours by propeller-driven aircraft. The following civilian and military fixed-wing aircraft are known to have landed on the island. They are listed according to size, in reverse order, to highlight the lowest-cost aircraft options:

- Cessna 182 (Adventist World Aviation)

- Norman Britten Island (Philippine Navy)

- Dornier DO-228 (Islands Aviation)

- GAF Nomad (Philippine Air Force)

- Lockheed Martin C-130 Hercules (Philippine Air Force)

|

Travel by sea

As of writing Pag-asa island does not have port facilities. Ships, therefore, have to weigh anchor off-shore — exposed to the waves of the West Philippine Sea — and transfer cargo to shore via small boats. This greatly limits the times of year when the island is accessible by sea, as well complicates disembarkation of potential investors and tourists. The struggle to build this port is chronicled in the following article: Timeline: Kalayaan Sheltered Port Project.

In addition to passage on-board Philippine Navy transports that reach Pag-asa on a quarterly basis, Pag-asa residents also travel to and from the Palawan via the MARINA-rated municipal service boat: M/L Queen Seagull. This is a 200-ton-capacity wooden boat that can get underway at 9 knots. From Puerto Princessa, via the Balabac strait, it can reach Pag-asa in 56 hours under favorable weather conditions. When sailing from Ulungan Bay on the western side of Palawan, total travel time is 32 hours. This is clearly not a destination for weekend get-aways.

|

Red tape

Of the nine occupied islands and above-water outposts that make up the municipality, only Pag-asa island — the seat of the municipal government — is currently open for civilian occupation. The rest of the municipality is restricted to military use. In addition to military personnel, Pag-asa hosts a community of fishing families and municipal workers that have established a variety of livelihood activities on the island and have even setup a municipal health center and an elementary school for the 20 children that call the island home.

The heavy military presence, and the international controversy over sovereignty over the islands and the waters around them, mean that anyone who seeks to travel to Pag-asa must obtain clearances from various Philippine government offices.

The Kalayaan Extension Office (KEO) in Puerto Princessa is available to assist potential travelers wade through a clearance system. As of June 30, 2014, the KEO can be found at the following location:

Kalayaan Extension Office

TELECOM Compound

Burgos St., Puerto Princesa City

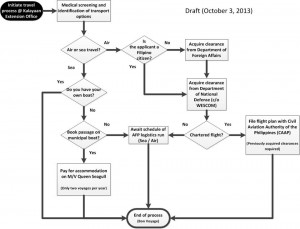

The following flowchart lays out the clearances required for the various modes of transportation. This critical information for any group seeking to organize a trip to Pag-asa. Note that individuals who possess their own boat require the least assistance. Filipino fishermen reportedly visit Pag-asa periodically with little or no advance notification beyond the obligatory radio communication with the Philippine Coast Guard personnel on the island.

|

The municipality maintains excellent rapport with the Western Philippine Command of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), which has jurisdiction over the islands, and is therefore familiar with clearance requirements at that level — which until a few years ago had largely been issued for domestic travelers.

The system’s complexities are particularly pronounced when dealing with foreign tourists. The KEO discovered this to its dismay in 2011 when an Australian-led international group of ham radio enthusiasts attempted to organize an expedition on Pag-asa. An all-Filipino group had already mounted a similar expedition in 2007 without difficulty (see DXJP 2007 here). But the international composition this particular group created complications. As related by the incumbent mayor, The Civil Aviation Administration of the Philippines (CAAP) would not approve a flight plan to the Pag-asa without clearance from the AFP. The AFP wouldn’t grant such clearance without approval of the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA). The DFA, in turn, did not appear to have a clear policy about granting foreigner-access to the island. The resulting delays eventually scuttled the expedition.

As of writing another group, this time led by Fil-Am enthusiasts, is gearing up for an ham radio expedition in 2015. With two years of advanced preparation time, the KEO, in cooperation with volunteers from various sectors, hopes to sort out all relevant procedures before the targeted expedition date. In April 2014, this group sent an advance party to Pag-asa to survey the expedition site. The advanced party used a combination of Philippine Navy transport and the Queen Seagull. This allowed them to stay on Pag-asa for five days (relevant Facebook discussion here).

|

Future prospects

Of the four key hurdles: weather, air access, sea access, and red tape — the latter is both the principal show-stopper, as well as the issue that should be the easiest to address. It is, after all, merely procedural and can resolved if all relevant agencies simply get together and work out a process. The reward for such inter-agency cooperation, is best exemplified by the Malaysian Spratlys outpost on Layang-Layang, which boasts of a thriving international diving destination with regular air transportation to its concrete runway — despite being co-located with a Malaysian Navy base.

Today, travel to Pag-asa Island is exceedingly difficult. Only the hardiest, logistically organized, travelers — often with professional interest — would dare to visit the island. But with the build up of attention towards the territory thanks to the power of social media and the efforts of ordinary Filipinos who were willing to take action beyond mouse-clicks and keyboard strokes, those difficulties are expected to diminish over time.

A Timawa Facebook extension for submarine warfare in the AFP

Saturday , 22, March 2014 Philippine Navy Leave a commentGiven the current nature of the country’s attitude towards defense, and the state of the AFP in general and the PN in particular, it will arguably take a LIFETIME to introduce submarines into the Philippine fleet. By promoting active and factual discussion about both the need and the challenges of establishing a submarine force, this FB group hopes to help shorten this process to at least a one lifetime . . . and not several.

The technical and organizational challenges of operating submarines (where the “pwede na” mentality can actually get people killed) define a goal for operational efficiency that, once met, can have a cascading effect throughout the fleet. The rejuvenating effect of this program upon the Philippine Navy could very well be likened to the effect of the Apollo program had on the US defense R&D program and aerospace industries. That, by itself, makes the program worth pursing for the long-term.

For those who are interested, here is the link to the group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/phsubmarine/

Started on Tuesday. 100 members in five days. Not too shabby 🙂

|

Flashback: AFP modernization – 2003 to 2006

Saturday , 22, February 2014 AFP modernization 1 CommentAs we ponder the never ending delays that plague defense acquisitions in the Aquino administration, it would be healthy to recall the state of affairs a mere 10 years ago. Back to the days of the Arroyo administration when modernization funding was completely pegged to the meager P5B annual allocation that the AFP modernization law had set as the floor for such funding. Despite its prevailing decrepit state, the AFP has actually come a long way. This article is an exploration of that recent-history. While the AFP modernization program covers a wide range of improvement efforts, from capability and materiel, bases, and even doctrines. This article focuses only one aspect of the effort: Capability and Materiel development.

The AFP’s long-standing dependency on US aid and Foreign Military Sales assistance meant that it sorely lacked the expertise required to conduct independent equipment acquisitions on the open defense market. Modernization proponents blame this deficiency for the delay in the implementation of the modernization program. Although the AFP Modernization Law had been signed in 1995, the first acquisitions as part of this program didn’t yield results until 2003.

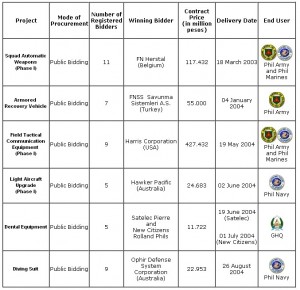

The first true modernization acquisition was the Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW) acquisition for the Philippine Army and the Philippine Marines. The contract to supply the first batch of weapons went to FN Herstal of Belgium which supplied the AFP with 402 factory-fresh M249 5.56mm SAWs. A follow-on purchase for SAWs took place in 2007, but that contract did not go to FN Herstal.

|

Another prominent was the acquisition of a Armored Recovery Vehicle from SS Savunma Sistemleri A. S. of Turkey. Reportedly hard lessons that Philippine armored units learned from the difficulties of operating without such vehicles in the 2000 Mindanao campaign against the MILF, only three years prior, reportedly served as a catalyst for the acquisition.

|

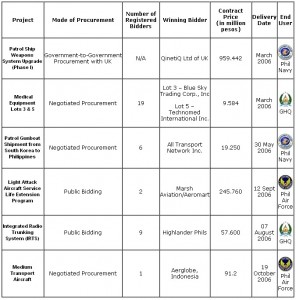

Other acquisitions from this landmark year and the following year are listed below. This table is a screen capture of an AFP modernization report.

|

Much to the dismay of external-defense advocates, the year 2005 radically altered the direction of the modernization program. At this point the Philippine Defense Reform program took effect and reworked the AFP Modernization Program into the Capability Upgrade Program, which shifted the focus of capability improvements to Internal Security Operations. The change, however, was not without justification. The loss of US aid as result of the closure of US military bases in Clark and Subic had taken its toll on the AFP’s material condition. Subsidies for the Philippine Air Force and Philippine Navy had wrecked havoc on maintenance cycles. Land-based mobility capability had reportedly dipped below 50% of the AFP needs. Troops were communicating with each other using Vietnam-era radios that were sending messages in the clear — which could be picked up by anyone with a commercial radio set that could be set to the same frequencies. The shift from the AFPMP to the CUP implemented a back-to-basics program that initially focused on a 5-year program to improve the AFP’s Move-Shoot-Communicate capabilities. Subsequent phases were designed to return the armed forces back to an external defense focus.

Whereas 2003 saw the first modernization acquisition of any kind, AFP modernization watchers remember 2005 as the year of the first true external-defense-relevant purchase: digital radios with military-grade encryption c/o Harris Communications. Many of the features of these radios are still classified. What is known however is that the communication-security they provided was game-changing for ISO — denying rebel signal intelligence of the data to which they had gotten accustomed — and brought the AFP into the 21st century as far as signal communication was concerned. The Philippine Army received 1,853 units of VHF/FM 2W radios, while 103 units went to the Philippine Marines. Additional radios were acquired in subsequent years.

|

|

Oriental Industry Ltd of South Korea received a contract to supply 3,100 sets of cermic-plate-based bulletproof vest and kevlar helmets for the Philippine Army and 5,000 kevlar helmets for the Marines. The first batch of 3,936 pieces of of ballistic helmets and 200 pieces of armor vests and plates were received on October 15, 2005 while the remainder were delivered December 2, 2005.

|

A contract to acquire twenty (20) refurbished UH-1H helicopters from Singapore Technologies Aerospace was signed on January 2004. The helicopters were delivered in seven batches with the delivery taking place August 2004. The last batch was delivered in May 2005.

|

Other acquisitions for the year are as follows:

|

In keeping with the reduced scope of the AFP’s upgrade program, a number of modest acquisitions took place in 2006. The Philippine Navy took delivery of two ex-South Korean Chamsuri class Patrol Killer Medium (PKM) boats where were commissioned as Tomas Batillo class gun boats. Because of a failure to find both interested and qualified bidders for the refurbishment of the boat in either South Korea or the Philippines, these were imported as-is in May of 2006. They were later upgraded.

|

The Philippine Air Force acquired 2nd-hand Fokker F-27 Fellowship transport aircraft, with upgraded FAA/ICAO-compliant avionics, via a negotiated procurement with Aeroglobe Ltd. Inc on October 2005. The aircraft was delivered in October 2006.

|

For the most part, capability upgrades in 2006 focused on maximizing existing assets. The Jacinto class OPVs received new electro-optical systems from QinetiQ Ltd and a 25mm Remote Controlled Weapon Station from MSI Defense Systems Ltd. The upgrades were performed at the Keppel Shipyard in Batangas and were completed in March 2006. This marked the first of three upgrade phases for the class. The second phase of the program involved an engineering upgrade that was eventually awarded to FF Cruz Inc on December 2006 after a series of bid failure for the project. Interestingly, the original winner of Phase 1, Keppel Shipyard, did not qualify for the 2nd phase of the program.

|

|

OV-10 Broncos of the Philippine Air Force underwent a Service Life Extension Program (SLEP) that included replacement of their original three-blade propellers with four-blade units and an overhaul of the aircraft’s engines. The winning contractor for this bid was the tandem of Marsh Aviation and Aeromart. The first batch of 4 brand new propellers and 4 overhauled engines were delivered on 5 February 2005. Four engines and 4 propellers were subsequently delivered on 19 September 2005. The delivery of 6 propellers on 24 October 2005 completed the delivery of the propellers. The 4 remaining engines arrived on 12 September 2006.

|

The following is a list of acquisition projects for this year.

|

2013: What’s happening with the AFP modernization program

Monday , 10, February 2014 AFP modernization 1 CommentNote: This article is also available on the Timawa.net forum on the long-standing “What’s happening with the AFP modernization program” thread.

In comparison with the past two years, 2013 was significantly muted from a modernization perspective. Many of the acquisitions that had been announced in previous years have either been delayed, fell through, or have delivery dates after 2013. It was, however, a noteworthy year for “Notices of Award” and acquisition negotiations.

The following projects have reached this stage in the acquisition process and are in various stages of post-qualification or terms-of-reference negotiation. These efforts aren’t expected to yield results till well after 2013 and their successful completion is not, by any stretch of the imagination, assured. For that reason they are separated from the actual acquisition list. Here is a sampling of prominent projects:

Philippine Air Force

- Lead-In Fighter Trainer / Surface Attack Aircraft: KAI F/A-50 Golden Eagle selected by way of the Defense System of Management (DSOM). Negotiations for terms of payment ongoing (see here)

- Attack Helicopter project: awarded to AgustaWestland for eight (8) AW109 helicopters due for delivery in 2014 (see here)

- UH-1H acquisition project: Awarded to Rice Aircraft services for 21 refurbished UH-1H helicopters (see here)

Philippine Navy

- National Coast Watch Center (NCWC): contract to design and construct the NCWC, with associated data integration with various stakeholders, awarded to Raytheon. Project completion scheduled for 2015. (see here)

Philippine Army / Philippine Marines

- M-4 assault rifle acquisition project: contract to supply 50,629 M-4 rifles awarded to Remington Arms Co (see here)

- M113A2 acquisition project: 142 Excess Defense Article (EDA) M113A2s are slated to be acquired from the United States (see here). The delivery date for this project is currently unclear

Arguably the most prominent arrival for the year was the BRP Ramon Alcaraz (PF-16) for the Philippine Navy. However this ship was officially turned over to the PN in 2012 and rightfully counts as an acquisition of that year. PF-16 was formally commissioned as a PN frigate in 2013 after having spent the better part of a year in Charleston, NC USA after the turnover from the USCG.

One aspect of the modernization program that did get traction in 2013 was the Government Arsenal, with the arrival of key quality assurance equipment. Training for a brand-new multi-station bullet assembly machine, which the DND Bids and Awards Committee (BAC) awarded to Waterbury Farrel in 2011, commenced in May 2013 (see here). However delivery of the GA-customized machine was slated for 2014.

The following list focuses on actual deliveries of equipment that were made in 2013. These include refurbishment efforts that returned previously inactive assets to service. This list is in flux as definitive confirmation of key projects remain pending as of publication.

|

Multi-Purpose Helicopter |  |

A batch of three (3) FLIR-equipped AgustaWestland AW109 Power helicopters were delivered in December 2013. Timawa discussion here |

| Small Unit Riverine Craft (SURC) |  |

Six (6) units of Silver Ships Small Unit Riverine Craft (SURC), which were acquired via FMS, were delivered to the Philippine Marines in September 2013. Timawa.net discussion here. | |

|

Combat Utility Helicopter |  |

The final two W-3 Sokol helicopters arrived from Poland in February 2013 here. This delivery completed the 8-helicopter order. |

| Refurbishment: AS-211 |  |

Two S211 aircraft were refurbished and returned to service. Timawa discussion here. | |

| Refurbishment: Sikorsky S-76 air ambulance |  |

Two S-76 helicopters were refurbished and converted into air ambulance configuration and returned to service in December 2013. Timawa discussion here. | |

|

5-ton truck acquisition (Philippine Army & Philippines Marines) |  |

Twelve units of Kia KM-500 5-ton trucks were acquired for the Philippine Army and Philippine Marine Corps. Timawa discussion here |

| 1/4 ton-truck acquisition |  |

A batch of 190 Kai KM-450 trucks, including 4 ceremonial car versions, were acquired. Timawa discussion here | |

| Flat-bed trailer acquisition | Flat-bed trailers for the transport of tracked vehicles were acquired. Timawa discussion here | ||

| Force protection equipment acquisition | Timawa discussion here | ||

| Global Position System (GPS) equipment | Timawa discussion here | ||

| 81mm mortar acquisition project |  |

One hundred (100) Serbian-made mortars were delivered as part of the Philippine Army’s 81mm mortar acquisition project. Timawa discussion here. | |

|

Universal Weapon Rest |  |

Universal Weapon Rest, manufactured by Saber (United Kingdom), used to test the accuracy of weapons such as as M-16, M-14, MSSR, SPR & various pistols was delivered and installed at the GA Ballistics Facility on September 16, 2013. Timawa discussion here. |

| Weighing and gauging machine |  |

An automated electronic weighing and gauging machine from Waterbury Farrel — a key component in the company’s ammunition production system — was delivered and installed at the GA. Timawa discussion here |

“Sea denial” vs “Sea Control”

Sunday , 5, January 2014 Philippine Air Force, Philippine Army, Philippine Navy Leave a commentThanks to a position paper published by Congressman Roilo Golez, the term “area denial” has entered mainstream Philippine social media discussions about tensions with China and territorial threats in the West Philippine Sea. But what exactly is “Sea Denial”? To fully appreciate that mission, one must also understand the super-set mission: “Sea Control”.

The following quotations were initially collected for the following discussion on the Timawa.net forum: Sea Control vs Sea Denial: Why small boats aren’t enough and provide an easy-to-follow layman’s guide to understanding these two concepts.

From an online excerpt of the book The Influence of Sea Power on History: 1600-1783, Boston: Little, Brown and Co, 1896 by Mahan, A. T. comes the following concise distinction between control and denial

Sea denial. Sea denial, or commerce-destroying, provides a means for harrying and tiring an enemy. It may be a means to avoid losing a war. It may cause “great individual injury and discontent”. But by itself, a sea denial strategy is not a war-winning one. Nor is it a particularly deterring strategy.

Sea Control. Sea control means, fundamentally, the ability to carry your, and your allies’, commerce across the seas and to provide the means to project force upon a hostile, distant shore. A sea controller must limit the sea denial capabilities of the enemy. To quote the Prophet again, “… when a question arises of control over distant regions, … it must ultimately be decided by naval power, …, which represents the communications that form so prominent a feature in all strategy.”

Between the two strategies, sea denial remains the lowest hanging fruit. Expensive capital ships are principal means of exercising Sea Control and is therefore often beyond the resources of most maritime nations. Even China initially started with this strategy as related by Hugh White, a professor of strategic studies at ANU. The paper not only points out China’s approach, but affirms the limitations of this strategy as explained above by Mahan

The Chinese have long understood that America’s sea control in the western Pacific has been the military foundation of its strategic primacy in Asia, and that the US Navy’s carriers are the key. They have therefore focused the formidable expansion of their naval and air forces over the past 20 years on trying to deprive the US of sea control by developing their capacity to sink American carriers. In this they appear to have been strikingly successful, to the point that US military leaders now acknowledge that their sea control in the western Pacific is slipping away.

But for China, depriving America of sea control is not the same as acquiring it themselves. Its naval strategy has focused on the much more limited aim that strategists call ”sea denial”: the ability to attack an adversary’s ships without being able to stop them attacking yours. These days, sea denial can be achieved without putting ships to sea, because land-based aircraft, long-range missiles and submarines can sink ships much more cost-effectively than other ships can. This is what China has done.

< Edited >

The central fact of modern naval warfare – which the Chinese grasp as well as anyone – is that sea denial is relatively easy to achieve, but control is extremely hard. We seem to be entering an era in which many countries can achieve sea denial where it matters to them most, but none can achieve sea control against any serious adversary.

The key take away from White’s thesis is the multi-dimensional nature of the strategy. To enable its own sea denial capability, the AFP needs to make investments in the airborne, maritime, and land-based systems listed above. The Philippine Navy currently has an ongoing acquisition project for brand new Frigates with explicit, albeit limited, Anti-Air, Anti-Surface, and Anti-Submarine Warfare capability. The Philippine Army is moving ahead with studies to acquire land-based Anti-Ship Missile systems. The Philippine Air Force is pursuing a variety of patrol and surface attack aircraft projects. All these efforts, as of writing, remain works-in-progress and their successful and timely completion is hardly assured.

While it is very unlikely that the Philippines will ever be able to make significant headway into sea control on its own, a sea-denial build-up will still put it in a better position to keep cadence with its allies. A coalition of countries with individual sea denial capabilities can approach sea control capability more effectively together than they could alone. A concerted effort to deploy sea-control-compatible assets, would also demonstrate the Philippines’ willingness to participate in an allied effort at sea control and establish its status as a reliable partner in such an allied effort, even if such assets can only maintain a tenuous presence in our EEZ when viewed in isolation.

A Self-Reliant Defense Posture (SRDP) roadmap and a DARPA-equivalent

Friday , 3, January 2014 Self-Reliant Defense Posture Leave a commentIn 2013, the Self-Reliant Defense Posture (SRDP) program — an ongoing albeit lackadaisical effort to create an indigenous defense industry — saw the most tangible display of high-level support in recent decades, when the Department of National Defense committed significant resources to the modernization of the Government Arsenal (GA), and facilitated the organization of the Defense Industries Association of the Philippines (DIAP). Both actions came on the heels of the successful entry into Philippine Navy service of a series of indigenously constructed marine vessels: The BRP Tagbanua (AT-296), the largest locally manufactured warship in history, and three Multi-Purpose Assault Craft (MPAC) Mk.II, arguably the fastest ships in the fleet. Both joined the fleet a year earlier.

|

|

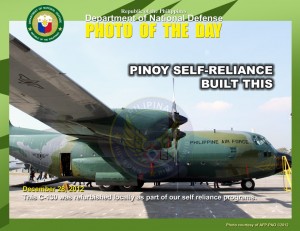

The year also saw the operational use C-130 #3633, the first Philippine Air Force Hercules transport aircraft to undergo Programmed Depot Management careof the 410th Maintenance Wing. It was an achievement many hoped would herald a new era in improved Hercules availability — all by Filipino hands.

|

Prospects for SRDP looked more promising in 2013 than it had ever been in recent years. But would it really last?

SRDP history shows that the Philippines neither lacks the imagination nor the talent to initiate domestic weapons production. However that same account also shows a long track record of failure to sustain such efforts. While the aforementioned recent SRDP developments showed a promising change in institutional outlook towards self-sufficiency, a change in the status quo will require more than a mere high-level peek into the current state of local-manufacture. This bump in interest must be institutionalized if it is ever to achieve any lasting effects.

Towards this end, the Philippines needs to establish an SRDP roadmap that clearly defines the following:

- The key defense articles that the Philippines needs to produce on it own to achieve its security goals

- Among the above-mentioned articles, which does the government intend to produce by itself and which ones will it farm out to Philippine industry

Before local industry commits the capital and resources necessary to research, develop, and eventually manufacture goods for the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), it needs to understand the nature of the demand. Without this, the pool of willing entrepreneurs will be slim at best . . . if not non-existent.

What we need to produce ourselves

SRDP sought to protect the country from geopolitically motivated disruptions in the supply of defense material, as well as to allow local industry and labor to benefit from defense expenditure. The AFP spends billions of pesos to both acquire new equipment and maintain existing ones. Unless local industry learns to satisfy these needs itself, all these funds would be destined for foreign vendors. SRDP was supposed to control this foreign-currency hemorrhage and help keep funds in-country.

The ability to pursue this program has been hampered by a multitude of factors: funding, lack of an industrial base, etc.. However, even if these prevailing limitations were addressed, the program’s objective shouldn’t be to completely eliminate importation of all defense equipment from foreign sources.

Very few countries actually design and/or manufacture every single defense article entirely on their own. Even the United States, for all its wealth and manufacturing capacity, still has its soldiers’ uniforms manufactured in eastern Europe and Asia. The official sidearm of the US Army is Italian: the M9 Barreta. Its standard Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW) and Medium Machine Gun (GPMG) are Belgian in origin: the M249 and M240 respectively, both built by Fabrique Nationale Manufacturing, Inc. (The latter replaced the iconic M60 machine gun) The UH-72 Lakota Light Utility Helicopter that recently entered service with the Army as a replacement for the UH-1 Huey and the OH-58 Kiowa is manufactured by Eurocopter. The most powerful military force in the world accepts the practicality and cost effectiveness of foreign solutions for their troops. A defense-spending fact that shouldn’t be lost upon SRDP advocates.

There are two main reasons for continuing to import items, both of which allow the AFP to acquire equipment in the most efficient and cost-effective manner:

- Time to deploy

- Economies of scale

Time-to-deploy

Decades of under-investment in national defense means that the AFP is in such a dire state that many of the items on the AFP modernization list are critical pieces of equipment that cannot be delayed by protracted development times. The military’s principal concerns are time-do-deploy and reliability. Acquiring off-the-shelf and proven equipment means that they can field weapon systems to the troops in the shortest possible time and with the confidence that the systems will work as advertised and as proven by other users around the world.

Off-the-shelf products can be deployed significantly faster than something that still needs to make the transition from the drawing board to the field. Take for example the largest military vessel produced by local industry for the Philippine Navy to date: the 51-meter BRP Tagbanua Landing Craft Utility (LCU). From bid initiation, to design definition, to actual delivery, this project took six years to complete. In contrast, Daewoo shipyard can complete an entire 122 meter Makassar class LPD in only four months using pre-existing designs.

Time-to-deploy considerations aren’t unique to the Philippines. Even the People’s Republic of China isn’t immune to such concerns, which is why they are still buying Russian engines for their vaunted new-generation aircraft instead of waiting for their design bureaus to perfect their designs.

How can time-to-deploy considerations be balanced with inevitable delays caused by development? Read on.

Economies of scale

Contrary to a sentiment popular amongst defense-commentators, in-country production will not automatically translate to lower cost of equipment. Setting up of industries is neither cheap nor easy. Acquisition of capital equipment and plant facilities – where none existed before – is a very financially intensive affair. All of those costs will have to be passed on to the buyer and unless the equipment is purchased in quantity, whatever is produced domestically could become the most expensive items of its kind in the world. (See older article about supply-and-demand). When buying equipment from foreign sources that are already ongoing concerns, one not only benefits from pre-existing infrastructure and experience, but also an existing global customer base that allows the vendor to spread out the cost of production resulting in lower per-unit costs.

Ultimately, SRDP program managers must be selective about what is produced locally. A balance between self-reliance and fiscal responsibility must be struck — all without compromising the AFP’s modernization efforts. A proposal for how to do this will be discussed later in this article.

Government-Private sector synergy: Who produces what?

Central to the DND’s ongoing efforts to reviving SRDP is the modernization of the Government Arsenal. The primacy of the Arsenal as an SRDP engine is affirmed in issuances such as Executive Order 303, Series of 2004 which states:

SECTION 1. Sourcing the Government Munitions Requirements. The AFP, PNP, and other government agencies are hereby directed to source their small arms ammunition and such other munitions requirements as may be available from the Government Arsenal;

To this end, the arsenal has increased production to levels that have now surpassed its previous output record of 20 million rounds set in 1978. Production for 2013 exceeded 23 million rounds. It is worth noting that the arsenal achieved this volume with its existing aging equipment. Much of the arsenal’s ongoing modernization efforts revolve around replacement or supplementation of existing equipment with state-of-the-art equivalents. Such as the new production line from Waterbury Farrel which will be dedicated to the production of M193/M855 5.56mm rounds. This and other new machines promise even more strides in production capacity thus allowing the GA to satisfy the routine ammunition needs of both the AFP and Philippine National Police (PNP).

|

The GA’s activities, however, do not end with ammunition production. With the creation of the Small Arms Repair and Upgrade Division (SARUD), the Arsenal has begun providing the AFP with small arms refurbishment services — bringing unserviceable rifles back to operational status. The SARUD is a key step towards the re-establishment of a small arms manufacturing capability back to the arsenal complex. A function that was lost when the martial-law era Elisco Tool stopped production of Philippine-made M-16s.

The growth in the arsenal’s capabilities, however, presents potential private sector SRDP players with an interesting quandry: “Will the business I setup eventually run into conflict with the GA’s offerings?” Solution: An SRDP roadmap.

A roadmap for SRDP

An SRDP roadmap would show where government agencies like the Government Arsenal growth are headed, thus allowing defense entrepreneurs to plan their investments accordingly and manage expectations. For example, a for-profit entity that produces ammunition would then understand that its role in SRDP would either be to simply provide surge capacity for national emergencies that call for more output than what the GA can accommodate otherwise it would need to enter into a Joint Venture (JV) with the DND — provided, of course, that the company is already a mature industry fixture. Areas of concern that are not on the plate of any government agency (e.g., GA, Philippine Aerospace Development Corp, Department of Science and Technology, etc.) would then be fair game and would merit more capital.

A side-benefit of maintaining a roadmap would be the definition of development horizons. It would give a timeline for when a particular piece of equipment is required, and therefore layout the AFP’s decision criteria for whether or not to wait for local prototypes to mature or to procure off-the-shelf. This avoids the time-to-deploy conflict between SRDP and the AFP modernization program that is mentioned above and would give private industry time to acquire the expertise and technology required to respond to a future government request for products. It also protects potential SRDP entrepreneurs from a state of limbo where their wares never leave the prototype stage. A situation that currently affects the “Project Trident Strike” Remote Control Weapon System (RCWS) developed by the Naval Sea Systems Command (NSSC) and the Mapua Institute of Technology. This RCWS has reportedly gone through several versions and modifications . . . and is no where near being deployed for operational testing.

|

This roadmap would need to encompass the SRDP development activities of all AFP services and government agencies (e.g., GA, PADC, etc.). It would avoid duplication of effort among these organizations, in the same manner that the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) rationalized the aerospace and rocketry programs of various entities within the US government, whose fractured efforts reportedly gave the Soviet Union the opportunity to take the opening lead in the space race.

Drafting and implementing a policy instrument of this breadth requires an entity with the expertise to grasp the technological hurdles that must be overcome, the military’s doctrinal considerations that must be satisfied, and possess the required business acumen to see the venture through. It must also have the means to either absorb technology transfers itself, or is able to farm this out qualified private sector entities.

To this end . . . the Philippines needs its equivalent to the American Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

A Philippine “DARPA”

Before crafting a Philippine DARPA, it would be best to understand what the original DARPA is and map it to the Philippine setting. Like NASA, DARPA was organized in response to the technological challenge that the Soviet Union presented during the space race and continues to play a key role in maintaining American leadership in military technology today. It was established in 1958 to oversee strategic application of United States research and development capacity to benefit of national defense and has since given rise to now-ubiquitous technologies such as the following:

- ARPANET – this effort to link computers into a national network became the basis for the modern Internet

- GPS – early DARPA work on a positioning system called “TRANSIT” laid the groundwork for what eventually became the current Global Positioning System

- M-16 assault rifle – DARPA initiated the Project Agile study that eventually created the rifle that has been the official US military assault rifle for the past 50 years

In recent years, it has organized technology competitions like the DARPA Robotics Challenge whose participants are currently tasked to develop robots that are capable of “assisting humans in responding to natural and man-made disasters”.

DARPA leverages both government and private sector research organizations for its projects. The agency’s 50th anniversary publication summarizes how it manages its projects as follows:

The DARPA program manager will seek out and fund researchers within U.S. defense contractors, private companies, and universities to bring the incipient concept into fruition. Thus, the research is outcome-driven to achieve results toward identified goals, not to pursue science per se. The goals may vary from demonstrating that an idea is technically feasible to providing proof-of-concept for an operational capability.

By design, DARPA leverages the industrial capacity and existing research infrastructure of the United States to achieve its goals. As a consequence — surprisingly, as related by the document linked above — DARPA doesn’t have its own organic research facilities and is entirely dependent on the capabilities of its research partners. DARPA projects are also focused on developing cutting-edge technologies, leaving comparatively less risky development projects to other procurement organizations within the Department of Defense. For this reason, a pure US-DARPA model is at best a source of inspiration for what can be done, but cannot be completely replicated in a country with limited manufacturing capacity like the Philippines.

Other nations who’ve adopted national policies that apply technological solutions to defense, and developed indigenous military industrial complexes have come up with their own variations of the DARPA concept. Consider the following countries: South Korea, India, Pakistan, and Singapore. These countries have very robust domestic defense materiel production capabilities and are even able to export their products, or take part in co-production ventures.

Lessons from South Korea

Thanks to the selection of the Korean Aerospace Industry FA-50 Golden Eagle for the Philippine Air Force’s Lead-In Fighter Trainer / Surface Attack Aircraft requirement, the Defense Acquisition Program Administration (DAPA) has gained prominence in the Philippine defense social media circles for its involvement in negotiations for the purchase of the aircraft. DAPA defense materiel acquired from South Korea and is tasked with the harnessing of manufacturing capacity of South Korean industry in that country’s defense.

|

It’s Website describes its function as follows. The DAPA is tasked implementation of the following national policies:

- Reinforcement of R&D in national defense

- Reinforcement of global competitiveness of the acquisition program

- Expansion of export support for the defense industry

- Prioritization of domestic R&D

- Strengthening cooperation of nation-wide science and technology

Like the US DARPA, this entity leverages already existing capabilities, but adds a marketing function to the equation because of its involvement in the export of South Korean defense technology.

Lessons from India

The Indian Department of Defense Production (DDP) takes a direct hand in the production of military equipment for the Indian military, from the HAL Tejas Light Combat Aircraft to the Arjun Main Battle Tank. The following organizations fall under this department’s control:

- Ordnance Factory Board (OFB)

- Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL)

- Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL)

- Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers Limited (GRSE)

- Goa Shipyard Limited (GSL)

- Hindustan Shipyard Limited (HSL)

- Mazagon Dock Limited (MDL)

- BEML Limited (BEML)

- Bharat Dynamics Limited (BDL)

- Mishra Dhatu Nigam Limited (MIDHANI)

- Directorate General of Quality Assurance (DGQA)

- Directorate General of Aeronautical Quality Assurance (DGAQA)

- Directorate of Standardisation (DOS)

- Directorate of Planning & Coordination (Dte. of P&C)

- Defence Exhibition Organisation (DEO)

- National Institute for Research & Development in Defence Shipbuilding (NIRDESH)

DDP efforts put India in a position to absorb foreign technologies as part of co-production ventures. Hindustan Aircraft Limited, for example, is now gearing up for local production of France’s most advanced combat aircraft to-date: Rafale Multi-Role Fighters. It is worth noting that the DDP was created at a time when the defense industry was the reserved for the public sector. In 2001, India opened the industry up to private sector involvement with up to 100% domestic participation and a maximum of 26% foreign direct investment.

Lessons from Pakistan

Like it’s similarly-named Indian counterpart, the Pakistani Ministry of Defense Production (MODP) participates in the manufacture of defense materiel for its armed forces. Among other achievements, it is the driving force behind local production of the Chinese JF-17 Light Combat Aircraft. Its Website describes its role as follows:

- Laying down policies or guidelines on all matters relating to defence production

- Procurement of firearms, weapons, ammunition, equipment, stores and explosives for the defence forces

- Declaration of industries necessary for the purpose of defence or for the prosecution of war

- Research and development of defence equipment and stores

- Co-ordination of defence science research with civil scientific research organizations

- Indigenous production and manufacture of defence equipment and stores

- Negotiations of agreements or MOUs for foreign assistance or collaboration and loans for purchase of military stores and technical know-how or transfer of technology

- Export of defence products

- Marketing and promotion of activities relating to export of defence products

- Coordinate production activities of all defence production organizations or establishments

Like the Indian model, the Pakistani government is deeply involved in the manufacture of its own defense articles. Like the South Korean DAPA, the MODP also takes steps to promote the export of Pakistani technology.

Lessons from Singapore

The Defense Science and Technology Agency (DSTA) is the latest Singaporean Ministry of Defense (MINDEF) organization dealing with defense-related R&D and procurement. Its official Website describes its role as follows:

- Acquiring platform and weapon systems for the SAF

- Advising MINDEF on all defence science and technology matters

- Designing, developing and maintaining defence systems and infrastructure

- Providing engineering and related services in defence areas

- Promoting and facilitating the development of defence science and technology in Singapore

It was established in 2000 and absorbed the functions of the what was then known as the Defense Technology Group (DTG). Tim Huxley, in his book Defending the Lion City, credited DTG with facilitating the creation of the Singaporean defense industry by acting as intermediaries between foreign defense companies who were willing to enter into Industrial Cooperation Programs (ICP) with Singapore and state-owned corporations to include the following:

- Chartered Industries of Singapore (CIS) – initially established in 1967 to produce small arms ammunition, it eventually branched out into license production of M-16 rifles. By the 70s this company was manufacturing larger weapons like machine guns, mortars, and grenade launchers

- Singapore Shipbuilding and Engineering – established in 1968 to maintaining and building naval vessels, entered into a technology transfer arrangement with the German firm Lurssen which eventually resulted in the construction of motor gun boats for the Royal Singaporean Navy

- Singapore Electronic and Engineering Ltd – established in 1969 to provide electronic engineering services for the Singaporean Air Force

These and other companies were brought under a holding company owned by the Singaporean Ministry of Finance but directed by MINDEF. By 1989 this holding company was restructured to accommodate diversification of its activities beyond purely military ventures such as electronics and engineering and renamed Singapore Technologies (ST) Holdings.

The ICP arrangements brokered by DTG, now DSTA, initially allowed Singaporean companies to accomplish self-reliance activities such as in-country manufacturing components for the Singaporean Air Force’s CH-47 Chinook helicopters and F-16 fighters. In 1999 it allowed Singapore to become a major participant in the US-UK Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program.

Implications for Philippine SRDP

Close scrutiny of the histories of the five self-reliance samples presented above offer a number of take-aways:

Stable self-reliance policies. The political decision to establish and maintain a domestic defense industry must be measured in decades, not mere years, to give these policies a chance to yield results. The Indian Tejas LCA program, for example, started in 1983 but even as late as 27 years later (as per Air Forces Monthly, May 2010) HAL was only producing its third Limited Series Production aircraft. Although the Tejas program is sometimes touted as an example of why domestic production is more a political decision than a practical one, it remains an example of the length of the gestation period for such endeavors — which go beyond time-in-grade timetables of individual officers, even beyond normal Presidential terms.

In the Philippines, a fair number of SRDP-related endeavors are conducted by service-level research organizations, often resulting from serendipitous pairings of SRDP-minded officers with industrialists and/or inventors willing to take a chance at dealing with the Philippine government. While efforts these do have their place in the grand scheme of things, the more complicated projects that take this route that have historically churned out one-off products. Often times, when time-in-grade issues force AFP personnel handling projects to leave their positions, development stops. Even when a project reaches completion, the departure of its original proponents often cause a change in the institutional stance towards the endeavor, resulting in either outright cancellation of the project or worse: indefinite postponement.

An SRDP-czar-like body such as Philippine DARPA, that is independent of the various services but is supported by the Department of National Defense, could presumably provide some stability to the these sorts of efforts.

Each to his own competence. The military shouldn’t run these programs alone. Other sectors of the government have a role to play and their respective skill-sets must be brought to bear (e.g., Finance, Trade & Industry, etc.). Singapore, for example, drew about the expertise of the Ministry of Finance to setup financial a holding entity to manage and finance the various self-reliance companies and architect their expansion into alternative profit centers. Ministry of Defense involvement was primarily at the technical and requirements definition level.

Interfacing with private sector entities such as the aforementioned Defense Industry Association, or similar organizations, could draw in additional talent that would otherwise not be available in government service.

Profit. Export of whatever defense articles are produced is a key goal. This not only extends the longevity of the production line, it also facilitates achievement of economies of scale. As mentioned earlier, the South Korean DAPA served as the primary point of contact for the South Korean defense industry.

Mature procurement system. For the non-American samples, their self-reliance programs are closely tied to their procurement procedures. Implementation of an SRDP roadmap cannot outstrip the efficiency of the DND-AFP’s overall acquisition system. Therefore advancement of the DND’s procurement service is essential to progress in SRDP.

In the Singaporean system, both foreign and domestic defense companies take part in open bidding for MinDef contracts. However procurement rules grant participants in Industrial Cooperation Programs with Singaporean companies additional “weight” in the final selection. There are no such protections in the Philippine setting, where the original SRDP Presidential Decree was actually amended in December 2003 through GPPB Resolution 06-2003 which deprived the government of the option to pursue SRDP acquisitions without subjecting potential participants to public bidding. This reflects an institutional attitude towards defense that generally hostile to SRDP.

Arguably, DARPA, DAPA, and DSTA represent the ideal free-market oriented relationship between the defense department and private industry. With indigenous defense-oriented companies actively taking part in developing tailor-made weapon systems in response to government requests and receiving production contracts in open competition with both domestic and foreign companies. At this point in history, the Philippines is nowhere near having this state of affairs. Despite SRDP being a 14-year-old program, the Philippines remains closer to the starting points for DDP, MODP, and DSTA than the present-day state of either DAPA or DARPA.

In crafting its equivalent to DARPA / DAPA / DDP / MODP / DSTA, the Philippines with two choices:

1. Select an existing government entity and expand its role

2. Create a completely new entity with resources drawn from existing entities

The United States faced a similar question when it evaluated its efforts to put a man on the Moon by the 70s. One of the candidates foundations for the expanded effort was the National Advisory Committee for Astronautics (NACA) which had been organized in 1915 and had been guiding American aerospace development since then. However, on the strength of the General Accounting Office which had judged NACA as having become too lethargic to keep pace with technological developments at the time, the US Congress enacted legislation that created an entirely and NASA was born. What route the Philippines ultimately takes will depend on similar evaluations of existing Philippines departments and/or government owned and controlled corporations.

The following organizations, theoretically at least, possess the key elements necessary for the creation of a Philippine DARPA:

Government Arsenal – as already mentioned earlier, this institution has been chosen as the lynchpin for renewed SRDP efforts. Its plant site in Limay, Bataan has been designated as a Defense Industrial Estate and the GA recently issued a bid invitation for consultancy services for the creation of a Master Development Plan for its continued development. For this reason, this is the logical base upon which a Philippine DARPA and SRDP-roadmap-custodian can be based. However, to approach the capabilities of the above-mentioned self-reliance organizations it will require significant expansion beyond its current areas of expertise which are primarily in manufacturing and research & development and currently focused ordnance and small arms technology.

Defense Industry Association – this is an group of Philippine companies that are have chosen to involve themselves in the domestic security market place. Its members include companies that were part of the original SRDP effort in the 70s and have varying levels of expertise in their respective fields. Arguably DIA members would be involved primarily in production and certain aspects of R&D, leaving responsibility for SRDP policy direction to the DND itself. How this relatively new entity develops remains to be seen

Philippine Aerospace Development Corp – this aerospace SRDP pioneer has assembled a total of 67 Britten Normal Islands and 44 BO-105 helicopters for the Philippine market and has established overhaul and maintenance facilities for various relatively low-technology aircraft and engine components. The company is currently in such a dismal state that the Commission on Audit recommended considering closure of the company in 2012. Despite being certified for BN Islander overhaul, that still didn’t make it the preferred vendor for the Philippine Navy’s Britten Normal Islander refurbishment programs which when to Hawker Pacific Ltd instead.

|

Philippine Investment & Trading Corporation – the PITC brings the necessary expertise to sell Philippine products to the world and would be a key player in the export of whatever defense articles the Philippine defense industry produces. This organization brings complex financial transaction experience to the table and was the AFP’s agent for past counter-trade deals that eventually acquired the SIAI-Marchetti S211 aircraft, and various communications equipment. What the organization lacks however, as reported for the Commission on Audit, is the technical expertise to adequately comprehend military requirements.

|

While the Government Arsenal’s central role in SRDP, at least in the near term to mid-term, is both logical and inevitable, where SRDP goes in the long term will depend on a NACA-NASA-like evaluation of the GA’s performance, as well as those of the other entities listed above. Only time will tell if the SRDP roadmap and responsibility for a Philippine DARPA will go to an existing SRDP actors or an entirely new entity. All that is certain is that if the goals of SRDP are ever to be achieved the status quo cannot continue.

This article is also available on the Timawa.net forum at the following location: http://www.timawa.net/forum/index.php?topic=36697.0

Where are the defense entrepreneurs?

Wednesday , 9, October 2013 Self-Reliant Defense Posture Leave a commentA fair number of discussions about SRDP, on various social groups, trumpet the abundance of skills in the Philippine labor force. This is how pronouncements typically go:

“We have so many engineers, computer graduates, OFWs with technology exposure overseas, etc. . . . so we should be able to make our own weapons!!!”.

These assertions, however, overlook one very important ingredient in every successful venture: The Entrepreneur

A weapons manufacturing company is a business. It needs start-up capital and it needs a market that it can satisfy and from which derive profits that sustain the business. Without capitalists and businessmen to get these ventures going . . . the much heralded engineers, computer graduates, etc. won’t have a company to work for and no weapon systems will be produced.

Even if a venture were to benefit from government assistance, to succeed there would still be a need for a business savy manager with an eye towards customer satisfaction as well as profitability. One way or another you need to attract business talent to the mix.

So when scratching our heads about why SRDP isn’t taking off, you shouldn’t just ask why aren’t our engineers being employed . . .

. . . you really also ought to ask, where are the defense-oriented entrepreneurs?

Why aren’t there any entrepreneurs lining up to produce weapons for the AFP despite the billions of pesos lined up for such projects?

That will require a discussion into government procurement practices, the problems plaguing the Self-Reliant Defense Posture program that are only now being addressed through the partnership between the Government Arsenal and a newly formed Philippine defense industry association, as well as gaps in national policy with regard to domestic production. You’d also have to go into the barriers to setting up any business in the Philippines in the first place. Topics that deserve an article all to themselves.

At this point let us simply salute the brave few who dared to risk time . . . and capital . . . to satisfy a customer whose rules and policies remain murky, and who decisions appear . . . randomly reversible.

This article was first posted on the Timawa.net forum here.

“To manufacture, or not to manufacture ?” . . . that is the question

Friday , 4, October 2013 Self-Reliant Defense Posture Leave a commentVarious defense commentators on social media have championed Philippine manufacture of all manner of weapons. From 20mm cannons to sophisticated aircraft and missiles. All too often, however, these Self-Reliant Defense Posture (SRDP) advocates side-step the need to be selective about what we push to make by ourselves. All forms of manufacture, to include weapons manufacture, is subject to laws of supply and demand. If the demand for an item — for example a 20mm cannon — cannot justify the cost of production, then it SHOULD NOT be produced.

The calculus is quite simple:

Per unit cost = Cost of production / Number of items produced

Cost of production includes capital expenditure for production equipment, cost of raw materials, salaries and consultancy fees, and other business start up costs.

The AFP cannot buy a weapon maker’s wares for forever, resulting in a limited production run. The Philippines could end up with the most expensive examples of a specific type of equipment.

To sustain the business, therefore, the weapon maker must be able to sell his wares overseas. Given the number of established players for various arms segments, a new company with no track record will be at a significant disadvantage. Whatever employment opportunities such a venture would open could very well be short-lived, as production lines shutdown for lack of demand. A fact of business life that established companies like Lockheed Martin and Saab face with their F-16 and Gripen production lines respectively.

The local defense industry’s focus on small arms manufacture reflects pragmatic recognition of the prevailing state of affairs. The market for that class of weapon remains relatively open. While the necessary equipment for quality manufacture still requires significant investment, the potential rewards still justify the risks.

Those risks increase in direct proportion to the complexity and capability of the weapon. This is already apparent even while still focusing on the small arms category, but simply going up to the high-end of the caliber scale — 12.7mm/0.50. There’s a reason why the Browning M-2 and the DShK are still kings of the hill in those caliber categories despite their age. Although there are indeed pretenders to those two thrones, these arguably will remain ankle-biters for the foreseeable future. The specialized nature of these weapons translates to limited market growth which is already served by existing solutions and suppliers — Military channel documentaries not withstanding.

There is prestige in make systems yourself. But such vanity pursuits have to be tempered by practicality. You would be hard-pressed to find a successful businessman, with an eye for profit, who would risk capital in saturated weapons markets. The Government Arsenal (GA) could theoretically get involved in such ventures since profit is not their goal. But that would still be a poor use of the people’s hard earned taxes. Those funds could be applied to more sustainable SRDP endeavors that give the people more bang for the buck. The GA’s push into small arms manufacture, and even the upcoming production of small bombs for the Philippine Air Force, as well as the Navy’s focus on relatively unsophisticated boats (e.g. MPACs, etc.) — all of which focus on already-present, and unsatisfied, local demand — reflect the conservative approach that effective stewardship of the people’s money requires.

Does this mean that the Philippines should abandon all hope of manufacturing systems beyond the simple ones that it can now? Not at all. It simply means that it needs to pick its battles and choose sunrise technologies that still offer hope for, at the very least, profitable market penetration or at best market leadership. Production of me-too products will yield limited benefit.

Patriotic considerations aside, some items are simply best bought from existing vendors overseas. For examples of companies that have successfully found niches in the local defense industry, see Sustainable defense manufacture in the Philippines.

===

This article is also on Timawa.net here: http://www.timawa.net/forum/index.php?topic=35948.0

At over 300 kilometers west of Palawan, the islands of the Municipality of Kalayaan are among the most remote communities in the Republic of the Philippines. It is in the same league as Basco in Batanes, and Mapun (Cagayan de Sulu) and Bongao in Tawi-Tawi. What sets this municipality apart, however, are the a unique combination of barriers-to-access that have greatly retarded its development. This article explores those challenges.

Travel period

Travel to the island is only advisable within a narrow window each year. As per reports from the office of the municipal mayor, the interval between April of May presents the best weather conditions for both sea and air travel. As will be described later in this article, optimal sea conditions are essential for travel by boat.

While weather information specifically for Pag-asa is unavailable on various online weather Websites, Weather.com publishes weather information for nearby Song Tu Tay island — formerly Pugad Island.

http://www.weather.com/weather/5-day/Song+Tu+Tay+South+West+Cay+VMXX0030:1:VM

Travel by air

From the air, Pag-asa’s defining feature is its 1.3 kilometer runway: Rancudo airfield. It is an unpaved coral airstrip, covered for the most part, by grass, named after a forward-thinking Commanding General of the Philippine Air Force who had it constructed in the early 70s.

|

As per a Memorandum of Agreement between the Armed Force of the Philippines and the Municipality of Kalayaan, signed in October 5, 2005, the airfield is open for joint civilian and military use. However, no regular commercial flights visit the island.

|

|

To date, Rancudo does not appear on the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines’ (CAAP) official list of airports and has not been rated as a civilian aerodrome. The latter reportedly presents aircraft charter companies with potential aircraft insurance issues, thus serving as a deterrent to service. As per the above agreement, responsibility for having Rancudo rated as an aerodrome rests with the municipality — whose attempts to initiate the rating process, thus far, have been unsuccessful. Rejuvenated efforts to pursue certification are currently underway by way of the KIG development forum FB group and on Timawa.net

Despite the lack of a civilian rating, on July 20, 2011, a Dornier DO-228 became one of the first chartered commercial flights to land on Pag-asa island. The passengers (which consisted of a congressional delegation and other government dignitaries) chartered the plane at a cost of PhP65,000 per flying-hour and PhP7,000 per hour on stand-by time, for a total price tag of P1.8M. The rates quoted were a function of the aircraft type and cheaper alternatives would have reportedly been available. The impact of the unrated airstrip on overall cost is unclear at this point.

Travel time to Pag-asa by air is approximately two to three hours by propeller-driven aircraft.

|

Travel by sea

As of writing Pag-asa island does not have port facilities. Ships, therefore, have to weigh anchor off-shore — exposed to the waves of the West Philippine Sea — and transfer cargo to shore via small boats. This greatly limits the times of year when the island is accessible by sea, as well complicates disembarkation of potential investors and tourists. The struggle to build this port is chronicled in the following article: Timeline: Kalayaan Sheltered Port Project.

In addition to passage on-board Philippine Navy transports that reach Pag-asa on a quarterly basis, Pag-asa residents also travel to and from the Palawan via the MARINA-rated municipal service boat: M/L Queen Seagull. This is a 200-ton-capacity wooden boat that can get underway at 9 knots. From Puerto Princessa, via the Balabac strait, it can reach Pag-asa in 56 hours under favorable weather conditions. When sailing from Ulungan Bay on the western side of Palawan, total travel time is 32 hours. Arguably, much too lengthy a transit for most visitors.

|

Red tape

Of the nine occupied islands and above-water outposts that make up the municipality, only Pag-asa island — the seat of the municipal government — is currently open for civilian occupation. The rest of the municipality is restricted to military use. In addition to military personnel, Pag-asa hosts a community of fishing families and municipal workers that have established a variety of livelihood activities on the island and have even setup a municipal health center and an elementary school for the 20 children that call the island home.

The heavy military presence, and the international controversy over sovereignty over the islands and the waters around them, mean that anyone who seeks to travel to Pag-asa must obtain clearances from various Philippine government offices.

The Kalayaan Extension Office (KEO) in Puerto Princessa is available to assist potential travelers wade through the clearance system. The municipality maintains excellent rapport with the Western Philippine Command of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), which has jurisdiction over the islands, and is therefore familiar with requirements at that level — which until a few years ago had largely been issued for domestic travelers.

|

The system’s complexities are particularly pronounced when dealing with foreign tourists. The KEO discovered this to its dismay in 2011 when an Australian-led international group of ham radio enthusiasts attempted to organize an expedition on Pag-asa. As related by the incumbent mayor, The Civil Aviation Administration of the Philippines (CAAP) would not approve a flight plan to the Pag-asa without clearance from the AFP. The AFP wouldn’t grant such clearance without approval of the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA). The DFA, in turn, did not appear to have a clear policy about granting foreigner-access to the island. The resulting delays eventually scuttled the expedition.

As of writing another group, this time led by Fil-Am enthusiasts, is gearing up for an ham radio expedition in 2015. With two years of advanced preparation time, the KEO, in cooperation with volunteers from various sectors, hopes to sort out all relevant procedures before the targeted expedition date.

Of the four key hurdles: weather, air access, sea access, and red tape — the latter is both the principal show-stopper, as well as the issue that should be the easiest to address. It is, after all, merely procedural and can resolved if all relevant agencies simply get together and work out a process. The reward for such inter-agency cooperation, is best exemplified by the Malaysian Spratlys outpost on Layang-Layang, which boasts of a thriving international diving destination with regular air transportation to its concrete runway — despite being co-located with a Malaysian Navy base.

Today, travel to Pag-asa Island is exceedingly difficult. Only the hardiest, or individuals with professional interest, would dare to visit the island. But with the build up of attention to the territory thanks to the power of social media and the efforts of ordinary Filipinos who were willing to take action beyond mouse-clicks and keyboard strokes, those difficulties are expected to diminish over time. The fate of the 2015 ham expedition will be an acid test for these efforts.