Philippine Defense Today (Adroth.ph)

In Defense of the Republic of the PhilippinesA Self-Reliant Defense Posture (SRDP) roadmap and a DARPA-equivalent

Friday , 3, January 2014 Self-Reliant Defense Posture Leave a commentIn 2013, the Self-Reliant Defense Posture (SRDP) program — an ongoing albeit lackadaisical effort to create an indigenous defense industry — saw the most tangible display of high-level support in recent decades, when the Department of National Defense committed significant resources to the modernization of the Government Arsenal (GA), and facilitated the organization of the Defense Industries Association of the Philippines (DIAP). Both actions came on the heels of the successful entry into Philippine Navy service of a series of indigenously constructed marine vessels: The BRP Tagbanua (AT-296), the largest locally manufactured warship in history, and three Multi-Purpose Assault Craft (MPAC) Mk.II, arguably the fastest ships in the fleet. Both joined the fleet a year earlier.

|

|

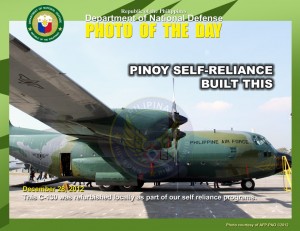

The year also saw the operational use C-130 #3633, the first Philippine Air Force Hercules transport aircraft to undergo Programmed Depot Management careof the 410th Maintenance Wing. It was an achievement many hoped would herald a new era in improved Hercules availability — all by Filipino hands.

|

Prospects for SRDP looked more promising in 2013 than it had ever been in recent years. But would it really last?

SRDP history shows that the Philippines neither lacks the imagination nor the talent to initiate domestic weapons production. However that same account also shows a long track record of failure to sustain such efforts. While the aforementioned recent SRDP developments showed a promising change in institutional outlook towards self-sufficiency, a change in the status quo will require more than a mere high-level peek into the current state of local-manufacture. This bump in interest must be institutionalized if it is ever to achieve any lasting effects.

Towards this end, the Philippines needs to establish an SRDP roadmap that clearly defines the following:

- The key defense articles that the Philippines needs to produce on it own to achieve its security goals

- Among the above-mentioned articles, which does the government intend to produce by itself and which ones will it farm out to Philippine industry

Before local industry commits the capital and resources necessary to research, develop, and eventually manufacture goods for the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), it needs to understand the nature of the demand. Without this, the pool of willing entrepreneurs will be slim at best . . . if not non-existent.

What we need to produce ourselves

SRDP sought to protect the country from geopolitically motivated disruptions in the supply of defense material, as well as to allow local industry and labor to benefit from defense expenditure. The AFP spends billions of pesos to both acquire new equipment and maintain existing ones. Unless local industry learns to satisfy these needs itself, all these funds would be destined for foreign vendors. SRDP was supposed to control this foreign-currency hemorrhage and help keep funds in-country.

The ability to pursue this program has been hampered by a multitude of factors: funding, lack of an industrial base, etc.. However, even if these prevailing limitations were addressed, the program’s objective shouldn’t be to completely eliminate importation of all defense equipment from foreign sources.

Very few countries actually design and/or manufacture every single defense article entirely on their own. Even the United States, for all its wealth and manufacturing capacity, still has its soldiers’ uniforms manufactured in eastern Europe and Asia. The official sidearm of the US Army is Italian: the M9 Barreta. Its standard Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW) and Medium Machine Gun (GPMG) are Belgian in origin: the M249 and M240 respectively, both built by Fabrique Nationale Manufacturing, Inc. (The latter replaced the iconic M60 machine gun) The UH-72 Lakota Light Utility Helicopter that recently entered service with the Army as a replacement for the UH-1 Huey and the OH-58 Kiowa is manufactured by Eurocopter. The most powerful military force in the world accepts the practicality and cost effectiveness of foreign solutions for their troops. A defense-spending fact that shouldn’t be lost upon SRDP advocates.

There are two main reasons for continuing to import items, both of which allow the AFP to acquire equipment in the most efficient and cost-effective manner:

- Time to deploy

- Economies of scale

Time-to-deploy

Decades of under-investment in national defense means that the AFP is in such a dire state that many of the items on the AFP modernization list are critical pieces of equipment that cannot be delayed by protracted development times. The military’s principal concerns are time-do-deploy and reliability. Acquiring off-the-shelf and proven equipment means that they can field weapon systems to the troops in the shortest possible time and with the confidence that the systems will work as advertised and as proven by other users around the world.

Off-the-shelf products can be deployed significantly faster than something that still needs to make the transition from the drawing board to the field. Take for example the largest military vessel produced by local industry for the Philippine Navy to date: the 51-meter BRP Tagbanua Landing Craft Utility (LCU). From bid initiation, to design definition, to actual delivery, this project took six years to complete. In contrast, Daewoo shipyard can complete an entire 122 meter Makassar class LPD in only four months using pre-existing designs.

Time-to-deploy considerations aren’t unique to the Philippines. Even the People’s Republic of China isn’t immune to such concerns, which is why they are still buying Russian engines for their vaunted new-generation aircraft instead of waiting for their design bureaus to perfect their designs.

How can time-to-deploy considerations be balanced with inevitable delays caused by development? Read on.

Economies of scale

Contrary to a sentiment popular amongst defense-commentators, in-country production will not automatically translate to lower cost of equipment. Setting up of industries is neither cheap nor easy. Acquisition of capital equipment and plant facilities – where none existed before – is a very financially intensive affair. All of those costs will have to be passed on to the buyer and unless the equipment is purchased in quantity, whatever is produced domestically could become the most expensive items of its kind in the world. (See older article about supply-and-demand). When buying equipment from foreign sources that are already ongoing concerns, one not only benefits from pre-existing infrastructure and experience, but also an existing global customer base that allows the vendor to spread out the cost of production resulting in lower per-unit costs.

Ultimately, SRDP program managers must be selective about what is produced locally. A balance between self-reliance and fiscal responsibility must be struck — all without compromising the AFP’s modernization efforts. A proposal for how to do this will be discussed later in this article.

Government-Private sector synergy: Who produces what?

Central to the DND’s ongoing efforts to reviving SRDP is the modernization of the Government Arsenal. The primacy of the Arsenal as an SRDP engine is affirmed in issuances such as Executive Order 303, Series of 2004 which states:

SECTION 1. Sourcing the Government Munitions Requirements. The AFP, PNP, and other government agencies are hereby directed to source their small arms ammunition and such other munitions requirements as may be available from the Government Arsenal;

To this end, the arsenal has increased production to levels that have now surpassed its previous output record of 20 million rounds set in 1978. Production for 2013 exceeded 23 million rounds. It is worth noting that the arsenal achieved this volume with its existing aging equipment. Much of the arsenal’s ongoing modernization efforts revolve around replacement or supplementation of existing equipment with state-of-the-art equivalents. Such as the new production line from Waterbury Farrel which will be dedicated to the production of M193/M855 5.56mm rounds. This and other new machines promise even more strides in production capacity thus allowing the GA to satisfy the routine ammunition needs of both the AFP and Philippine National Police (PNP).

|

The GA’s activities, however, do not end with ammunition production. With the creation of the Small Arms Repair and Upgrade Division (SARUD), the Arsenal has begun providing the AFP with small arms refurbishment services — bringing unserviceable rifles back to operational status. The SARUD is a key step towards the re-establishment of a small arms manufacturing capability back to the arsenal complex. A function that was lost when the martial-law era Elisco Tool stopped production of Philippine-made M-16s.

The growth in the arsenal’s capabilities, however, presents potential private sector SRDP players with an interesting quandry: “Will the business I setup eventually run into conflict with the GA’s offerings?” Solution: An SRDP roadmap.

A roadmap for SRDP

An SRDP roadmap would show where government agencies like the Government Arsenal growth are headed, thus allowing defense entrepreneurs to plan their investments accordingly and manage expectations. For example, a for-profit entity that produces ammunition would then understand that its role in SRDP would either be to simply provide surge capacity for national emergencies that call for more output than what the GA can accommodate otherwise it would need to enter into a Joint Venture (JV) with the DND — provided, of course, that the company is already a mature industry fixture. Areas of concern that are not on the plate of any government agency (e.g., GA, Philippine Aerospace Development Corp, Department of Science and Technology, etc.) would then be fair game and would merit more capital.

A side-benefit of maintaining a roadmap would be the definition of development horizons. It would give a timeline for when a particular piece of equipment is required, and therefore layout the AFP’s decision criteria for whether or not to wait for local prototypes to mature or to procure off-the-shelf. This avoids the time-to-deploy conflict between SRDP and the AFP modernization program that is mentioned above and would give private industry time to acquire the expertise and technology required to respond to a future government request for products. It also protects potential SRDP entrepreneurs from a state of limbo where their wares never leave the prototype stage. A situation that currently affects the “Project Trident Strike” Remote Control Weapon System (RCWS) developed by the Naval Sea Systems Command (NSSC) and the Mapua Institute of Technology. This RCWS has reportedly gone through several versions and modifications . . . and is no where near being deployed for operational testing.

|

This roadmap would need to encompass the SRDP development activities of all AFP services and government agencies (e.g., GA, PADC, etc.). It would avoid duplication of effort among these organizations, in the same manner that the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) rationalized the aerospace and rocketry programs of various entities within the US government, whose fractured efforts reportedly gave the Soviet Union the opportunity to take the opening lead in the space race.

Drafting and implementing a policy instrument of this breadth requires an entity with the expertise to grasp the technological hurdles that must be overcome, the military’s doctrinal considerations that must be satisfied, and possess the required business acumen to see the venture through. It must also have the means to either absorb technology transfers itself, or is able to farm this out qualified private sector entities.

To this end . . . the Philippines needs its equivalent to the American Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

A Philippine “DARPA”

Before crafting a Philippine DARPA, it would be best to understand what the original DARPA is and map it to the Philippine setting. Like NASA, DARPA was organized in response to the technological challenge that the Soviet Union presented during the space race and continues to play a key role in maintaining American leadership in military technology today. It was established in 1958 to oversee strategic application of United States research and development capacity to benefit of national defense and has since given rise to now-ubiquitous technologies such as the following:

- ARPANET – this effort to link computers into a national network became the basis for the modern Internet

- GPS – early DARPA work on a positioning system called “TRANSIT” laid the groundwork for what eventually became the current Global Positioning System

- M-16 assault rifle – DARPA initiated the Project Agile study that eventually created the rifle that has been the official US military assault rifle for the past 50 years

In recent years, it has organized technology competitions like the DARPA Robotics Challenge whose participants are currently tasked to develop robots that are capable of “assisting humans in responding to natural and man-made disasters”.

DARPA leverages both government and private sector research organizations for its projects. The agency’s 50th anniversary publication summarizes how it manages its projects as follows:

The DARPA program manager will seek out and fund researchers within U.S. defense contractors, private companies, and universities to bring the incipient concept into fruition. Thus, the research is outcome-driven to achieve results toward identified goals, not to pursue science per se. The goals may vary from demonstrating that an idea is technically feasible to providing proof-of-concept for an operational capability.

By design, DARPA leverages the industrial capacity and existing research infrastructure of the United States to achieve its goals. As a consequence — surprisingly, as related by the document linked above — DARPA doesn’t have its own organic research facilities and is entirely dependent on the capabilities of its research partners. DARPA projects are also focused on developing cutting-edge technologies, leaving comparatively less risky development projects to other procurement organizations within the Department of Defense. For this reason, a pure US-DARPA model is at best a source of inspiration for what can be done, but cannot be completely replicated in a country with limited manufacturing capacity like the Philippines.

Other nations who’ve adopted national policies that apply technological solutions to defense, and developed indigenous military industrial complexes have come up with their own variations of the DARPA concept. Consider the following countries: South Korea, India, Pakistan, and Singapore. These countries have very robust domestic defense materiel production capabilities and are even able to export their products, or take part in co-production ventures.

Lessons from South Korea

Thanks to the selection of the Korean Aerospace Industry FA-50 Golden Eagle for the Philippine Air Force’s Lead-In Fighter Trainer / Surface Attack Aircraft requirement, the Defense Acquisition Program Administration (DAPA) has gained prominence in the Philippine defense social media circles for its involvement in negotiations for the purchase of the aircraft. DAPA defense materiel acquired from South Korea and is tasked with the harnessing of manufacturing capacity of South Korean industry in that country’s defense.

|

It’s Website describes its function as follows. The DAPA is tasked implementation of the following national policies:

- Reinforcement of R&D in national defense

- Reinforcement of global competitiveness of the acquisition program

- Expansion of export support for the defense industry

- Prioritization of domestic R&D

- Strengthening cooperation of nation-wide science and technology

Like the US DARPA, this entity leverages already existing capabilities, but adds a marketing function to the equation because of its involvement in the export of South Korean defense technology.

Lessons from India

The Indian Department of Defense Production (DDP) takes a direct hand in the production of military equipment for the Indian military, from the HAL Tejas Light Combat Aircraft to the Arjun Main Battle Tank. The following organizations fall under this department’s control:

- Ordnance Factory Board (OFB)

- Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL)

- Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL)

- Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers Limited (GRSE)

- Goa Shipyard Limited (GSL)

- Hindustan Shipyard Limited (HSL)

- Mazagon Dock Limited (MDL)

- BEML Limited (BEML)

- Bharat Dynamics Limited (BDL)

- Mishra Dhatu Nigam Limited (MIDHANI)

- Directorate General of Quality Assurance (DGQA)

- Directorate General of Aeronautical Quality Assurance (DGAQA)

- Directorate of Standardisation (DOS)

- Directorate of Planning & Coordination (Dte. of P&C)

- Defence Exhibition Organisation (DEO)

- National Institute for Research & Development in Defence Shipbuilding (NIRDESH)

DDP efforts put India in a position to absorb foreign technologies as part of co-production ventures. Hindustan Aircraft Limited, for example, is now gearing up for local production of France’s most advanced combat aircraft to-date: Rafale Multi-Role Fighters. It is worth noting that the DDP was created at a time when the defense industry was the reserved for the public sector. In 2001, India opened the industry up to private sector involvement with up to 100% domestic participation and a maximum of 26% foreign direct investment.

Lessons from Pakistan

Like it’s similarly-named Indian counterpart, the Pakistani Ministry of Defense Production (MODP) participates in the manufacture of defense materiel for its armed forces. Among other achievements, it is the driving force behind local production of the Chinese JF-17 Light Combat Aircraft. Its Website describes its role as follows:

- Laying down policies or guidelines on all matters relating to defence production

- Procurement of firearms, weapons, ammunition, equipment, stores and explosives for the defence forces

- Declaration of industries necessary for the purpose of defence or for the prosecution of war

- Research and development of defence equipment and stores

- Co-ordination of defence science research with civil scientific research organizations

- Indigenous production and manufacture of defence equipment and stores

- Negotiations of agreements or MOUs for foreign assistance or collaboration and loans for purchase of military stores and technical know-how or transfer of technology

- Export of defence products

- Marketing and promotion of activities relating to export of defence products

- Coordinate production activities of all defence production organizations or establishments

Like the Indian model, the Pakistani government is deeply involved in the manufacture of its own defense articles. Like the South Korean DAPA, the MODP also takes steps to promote the export of Pakistani technology.

Lessons from Singapore

The Defense Science and Technology Agency (DSTA) is the latest Singaporean Ministry of Defense (MINDEF) organization dealing with defense-related R&D and procurement. Its official Website describes its role as follows:

- Acquiring platform and weapon systems for the SAF

- Advising MINDEF on all defence science and technology matters

- Designing, developing and maintaining defence systems and infrastructure

- Providing engineering and related services in defence areas

- Promoting and facilitating the development of defence science and technology in Singapore

It was established in 2000 and absorbed the functions of the what was then known as the Defense Technology Group (DTG). Tim Huxley, in his book Defending the Lion City, credited DTG with facilitating the creation of the Singaporean defense industry by acting as intermediaries between foreign defense companies who were willing to enter into Industrial Cooperation Programs (ICP) with Singapore and state-owned corporations to include the following:

- Chartered Industries of Singapore (CIS) – initially established in 1967 to produce small arms ammunition, it eventually branched out into license production of M-16 rifles. By the 70s this company was manufacturing larger weapons like machine guns, mortars, and grenade launchers

- Singapore Shipbuilding and Engineering – established in 1968 to maintaining and building naval vessels, entered into a technology transfer arrangement with the German firm Lurssen which eventually resulted in the construction of motor gun boats for the Royal Singaporean Navy

- Singapore Electronic and Engineering Ltd – established in 1969 to provide electronic engineering services for the Singaporean Air Force

These and other companies were brought under a holding company owned by the Singaporean Ministry of Finance but directed by MINDEF. By 1989 this holding company was restructured to accommodate diversification of its activities beyond purely military ventures such as electronics and engineering and renamed Singapore Technologies (ST) Holdings.

The ICP arrangements brokered by DTG, now DSTA, initially allowed Singaporean companies to accomplish self-reliance activities such as in-country manufacturing components for the Singaporean Air Force’s CH-47 Chinook helicopters and F-16 fighters. In 1999 it allowed Singapore to become a major participant in the US-UK Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program.

Implications for Philippine SRDP

Close scrutiny of the histories of the five self-reliance samples presented above offer a number of take-aways:

Stable self-reliance policies. The political decision to establish and maintain a domestic defense industry must be measured in decades, not mere years, to give these policies a chance to yield results. The Indian Tejas LCA program, for example, started in 1983 but even as late as 27 years later (as per Air Forces Monthly, May 2010) HAL was only producing its third Limited Series Production aircraft. Although the Tejas program is sometimes touted as an example of why domestic production is more a political decision than a practical one, it remains an example of the length of the gestation period for such endeavors — which go beyond time-in-grade timetables of individual officers, even beyond normal Presidential terms.

In the Philippines, a fair number of SRDP-related endeavors are conducted by service-level research organizations, often resulting from serendipitous pairings of SRDP-minded officers with industrialists and/or inventors willing to take a chance at dealing with the Philippine government. While efforts these do have their place in the grand scheme of things, the more complicated projects that take this route that have historically churned out one-off products. Often times, when time-in-grade issues force AFP personnel handling projects to leave their positions, development stops. Even when a project reaches completion, the departure of its original proponents often cause a change in the institutional stance towards the endeavor, resulting in either outright cancellation of the project or worse: indefinite postponement.

An SRDP-czar-like body such as Philippine DARPA, that is independent of the various services but is supported by the Department of National Defense, could presumably provide some stability to the these sorts of efforts.

Each to his own competence. The military shouldn’t run these programs alone. Other sectors of the government have a role to play and their respective skill-sets must be brought to bear (e.g., Finance, Trade & Industry, etc.). Singapore, for example, drew about the expertise of the Ministry of Finance to setup financial a holding entity to manage and finance the various self-reliance companies and architect their expansion into alternative profit centers. Ministry of Defense involvement was primarily at the technical and requirements definition level.

Interfacing with private sector entities such as the aforementioned Defense Industry Association, or similar organizations, could draw in additional talent that would otherwise not be available in government service.

Profit. Export of whatever defense articles are produced is a key goal. This not only extends the longevity of the production line, it also facilitates achievement of economies of scale. As mentioned earlier, the South Korean DAPA served as the primary point of contact for the South Korean defense industry.

Mature procurement system. For the non-American samples, their self-reliance programs are closely tied to their procurement procedures. Implementation of an SRDP roadmap cannot outstrip the efficiency of the DND-AFP’s overall acquisition system. Therefore advancement of the DND’s procurement service is essential to progress in SRDP.

In the Singaporean system, both foreign and domestic defense companies take part in open bidding for MinDef contracts. However procurement rules grant participants in Industrial Cooperation Programs with Singaporean companies additional “weight” in the final selection. There are no such protections in the Philippine setting, where the original SRDP Presidential Decree was actually amended in December 2003 through GPPB Resolution 06-2003 which deprived the government of the option to pursue SRDP acquisitions without subjecting potential participants to public bidding. This reflects an institutional attitude towards defense that generally hostile to SRDP.

Arguably, DARPA, DAPA, and DSTA represent the ideal free-market oriented relationship between the defense department and private industry. With indigenous defense-oriented companies actively taking part in developing tailor-made weapon systems in response to government requests and receiving production contracts in open competition with both domestic and foreign companies. At this point in history, the Philippines is nowhere near having this state of affairs. Despite SRDP being a 14-year-old program, the Philippines remains closer to the starting points for DDP, MODP, and DSTA than the present-day state of either DAPA or DARPA.

In crafting its equivalent to DARPA / DAPA / DDP / MODP / DSTA, the Philippines with two choices:

1. Select an existing government entity and expand its role

2. Create a completely new entity with resources drawn from existing entities

The United States faced a similar question when it evaluated its efforts to put a man on the Moon by the 70s. One of the candidates foundations for the expanded effort was the National Advisory Committee for Astronautics (NACA) which had been organized in 1915 and had been guiding American aerospace development since then. However, on the strength of the General Accounting Office which had judged NACA as having become too lethargic to keep pace with technological developments at the time, the US Congress enacted legislation that created an entirely and NASA was born. What route the Philippines ultimately takes will depend on similar evaluations of existing Philippines departments and/or government owned and controlled corporations.

The following organizations, theoretically at least, possess the key elements necessary for the creation of a Philippine DARPA:

Government Arsenal – as already mentioned earlier, this institution has been chosen as the lynchpin for renewed SRDP efforts. Its plant site in Limay, Bataan has been designated as a Defense Industrial Estate and the GA recently issued a bid invitation for consultancy services for the creation of a Master Development Plan for its continued development. For this reason, this is the logical base upon which a Philippine DARPA and SRDP-roadmap-custodian can be based. However, to approach the capabilities of the above-mentioned self-reliance organizations it will require significant expansion beyond its current areas of expertise which are primarily in manufacturing and research & development and currently focused ordnance and small arms technology.

Defense Industry Association – this is an group of Philippine companies that are have chosen to involve themselves in the domestic security market place. Its members include companies that were part of the original SRDP effort in the 70s and have varying levels of expertise in their respective fields. Arguably DIA members would be involved primarily in production and certain aspects of R&D, leaving responsibility for SRDP policy direction to the DND itself. How this relatively new entity develops remains to be seen

Philippine Aerospace Development Corp – this aerospace SRDP pioneer has assembled a total of 67 Britten Normal Islands and 44 BO-105 helicopters for the Philippine market and has established overhaul and maintenance facilities for various relatively low-technology aircraft and engine components. The company is currently in such a dismal state that the Commission on Audit recommended considering closure of the company in 2012. Despite being certified for BN Islander overhaul, that still didn’t make it the preferred vendor for the Philippine Navy’s Britten Normal Islander refurbishment programs which when to Hawker Pacific Ltd instead.

|

Philippine Investment & Trading Corporation – the PITC brings the necessary expertise to sell Philippine products to the world and would be a key player in the export of whatever defense articles the Philippine defense industry produces. This organization brings complex financial transaction experience to the table and was the AFP’s agent for past counter-trade deals that eventually acquired the SIAI-Marchetti S211 aircraft, and various communications equipment. What the organization lacks however, as reported for the Commission on Audit, is the technical expertise to adequately comprehend military requirements.

|

While the Government Arsenal’s central role in SRDP, at least in the near term to mid-term, is both logical and inevitable, where SRDP goes in the long term will depend on a NACA-NASA-like evaluation of the GA’s performance, as well as those of the other entities listed above. Only time will tell if the SRDP roadmap and responsibility for a Philippine DARPA will go to an existing SRDP actors or an entirely new entity. All that is certain is that if the goals of SRDP are ever to be achieved the status quo cannot continue.

This article is also available on the Timawa.net forum at the following location: http://www.timawa.net/forum/index.php?topic=36697.0