Philippine Defense Today (Adroth.ph)

In Defense of the Republic of the PhilippinesA sustainable, whole-nation, “Kobayashi Maru” solution to China’s aggression

Saturday , 1, December 2018 geopolitics Leave a commentThis thesis (originally posted on the Defense of the Republic of the Philippines forum on August 3, 2018) attempts to answer the hotly debated question:

“What is happening to Philippine policy with China and the West Philippine Sea???”

While the defense of the Republic of the Philippines is the focal point for this thesis, there can be no effective discussion about defense if it is narrowly confined to weaponry and military / law enforcement considerations alone.

You can’t talk about a birthday cake by focusing on the icing while paying no attention to the underlying cake.

Policies made outside the military sphere define what can be done within that sphere. For that reason, proper understanding of the Duterte administration’s approach to the China problem in the West Philippine Sea — regardless of whether the reader agrees with it or not — is a precondition for meaningful discussions about Philippine sovereignty.

The best way to read this thesis is to proceed linearly, from start to finish, in the order it was written. However, being 30 pages long, this thread index was created to facilitate navigation. Each sub-topic is given it own summary, thus allowing the reader to jump directly to topics of greater interest.

At the end of the day, the goal of the thesis isn’t to advocate any single political point of view. It is merely to understand what the current administration is attempting to do . . .

. . . without the noise of partisan politics.

Once that understanding is achieved, then — and only then — can the average Filipino come up with an INFORMED opinion of prevailing policies, and meaningfully argue for OR against these policies.

| Section | Sub-Section | Description | ||

| Chinese timing | By 2014, China knew that conditions were right to advance its interests at the expense of its rivals — and it did. | |||

| United States | The US was in no shape to mount a conventional war. The two wars-without-end in Iraq and Afghanistan had left the US electorate with little appetite for yet another armed conflict. | |||

| Japan | China’s shipbuilding spree has eclipsed the Japanese Coast Guard, both in terms of number and size of vessels. | |||

| Australia | . . . struggling to contain China within its own sphere of influence: from Vanuatu to Papua New Guinea. | |||

| ASEAN | While much has been said about Duterte’s refusal to use ASEAN as a venue for protesting Chinese actions in the West Philippine Sea, ASEAN had already been defanged years earlier when Cambodia actively blocked any attempt association statements that would be unfavorable to China. First in 2012, then again in 2016. | |||

| The scramble for a PH response | Open war with China and surrender are invalid options. Justice Antonio Carpio prefers a “third option” that hides behind the Mutual Defense Treaty with the US and diplomacy. But how viable is this option? | |||

| Evaluating the 3rd option: UNCLOS | The UNCLOS ruling invalidated China’s 9-dashed line. But it did not actually affirm Philippine sovereignty over the West Philippine Sea | |||

| Evaluating the 3rd option: MDT | The US-PH MDT was deliberately crafted so that it would not commit the United States to support the Philippines if it did not agree with Philippine claims. Not all mutual defense treaties are created equal. | |||

| Treaty that created NATO | The US explicitly guarantees support in the event a member of the NATO alliance is attacked. The commonly held perception is that the Philippines enjoys the same protection. Careful perusal of the MDT shows otherwise | |||

| Treaty between the US and Japan | While the US-JP treaty did not guarantee an automatic response, US policy has recognized JP sovreignty over the Senkakus. It is important to understand why the US felt compelled to support Japan | |||

| Vietnam’s losses | Despite being 8th largest importer of weaponry in the world, whose inventory includes everything from Scud medium-range ballistic missiles, modern submarines, frigates, multi-role fighters, and surface-to-surface missiles, Vietnam is at the very least in a stalemate with China it can’t hope to outlast.

The Philippine strategy under Duterte, in contrast, has its sights on a more favorable outcome. |

|||

| Indonesian calculations | In addition to a regionally strong military, Indonesia has a lock on certain critical Chinese exports which China needs, is on the outer edge of China’s claims and is not as important as the Philippines and Vietnam, China officially recognizes Vietnam’s claims. | |||

| Defining the parameters of the problem | A Philippines that defiantly stands up for itself, but lacks, the military strength of Vietnam, the economic resilience and geographical distance of Indonesia, and is dependent on allies that are either threatened by China or are embroiled in other domestic and geopolitical concerns, could very well become low-hanging fruit for a display of Chinese political power. Not so much for international consumption, but for the benefit of the enemy that the Chinese leadership fears most: internal Chinese politics. | |||

| The way forward | War is clearly not an option, for reasons already detailed earlier and as outlined by the President in his speech above. Surrender would violate the constitution, and is therefore an equally invalid option. The ability to hide behind our allies is questionable as is the validity of the opposition’s 3rd option.

Duterte needed a 4th option |

|||

| The 4th option | If China were a bully, Option 1 (war) would have started a fight with the bully that could only end with us in either a wheelchair or the grave. Option 2, surrender, would leave us with nothing. Option 3 (Carpio, et. al.) would have us pick a fight with the bully while hiding behind a big, but distracted neighbor that retains the option to go to the movies whenever he wants . . . regardless of our fitness to resort to option 1 when we are left alone.

Option 4 would have the bully wonder why he had to act like a douche bag in the first place . . . and learn to play nice. It would not make the bully go away, but would essentially make him leave us alone. All the while . . . wondering who we would side with if he ever decided to picked a fight with our big neighbor. |

|||

| What has been prevented | Fishermen are no longer being water-cannoned away from Panatag. Despite having been occupied since 2012, with island-building campaign gaining momentum, China hasn’t built on anything on Panatag. | |||

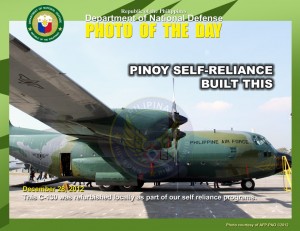

| What has already, or is currently, being done | Photographic evidence points to improvements on garrisons in the KIG that weren’t done in the previous administration | |||

| Implementing the 4th option |  |

|||

| Step one: Rebooting PH-CN relations | Implement a variation of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” adage, and flipped the strategy into: “to make a friend of my enemy, make him feel like we have a common enemy”. This is why Duterte is openly bad mouthing our allies — who now actually understand that this is all essentially geopolitical theater as part of a plan to jump-start PH-CN relations.

The administration is banking on the strength of US-PH relationships, as well as of those of its traditional allies, to “absorb” the optics of Duterte’s over-selling of its Chinese charm offensive. After all, if it really were possible to undo years of good relations with mere words . . . then those relationships really weren’t as strong advertised. |

|||

| Step two: Acclimatize China to submitting to Philippine law | This is about training the dragon to obey commands . . . and setting up test cases to measure compliance. | |||

| Step three: Ongoing cooperation | China’s greed, not Philippines weapons, will keep China under control.

This would require even greater commercial engagement with China. So much so that it would actually compel China to respect Philippine law and Philippine claims, to avoid jeopardizing these investments. This would flip the tables on China from one where the Philippines feared Chinese embargoes on Philippine goods to one where China will experience “economic pain” should it choose to violate Philippine interests. |

|||

| Continued build up of Philippine economic defenses | A sustainable response to Chinese aggression isn’t just about buying weaponry, it is actually about making the Philippines — as a country — globally competitive.

This is where the build-build-build initiative comes in: Using the dragon’s own resources to create the financial whip to keep him in line. |

|||

| Learn from the experiences of Sri Lanka, et. al. | This topic outlines how countries fall into China’s debt trap, and how the Philippines actually differs from these in-progress economic disasters. | |||

| Pakistan’s gamble | 85% of Pakistan’s debt is Chinese. But who REALLY has who under control, in light of Pakistan’s geopolitical calculation . . . when Pakistan’s economic corridor actually starts on their China’s equivalent to Mindanao?

|

|||

| Israel & Indonesia: Dancing with a dragon | If loans with China are really recipes for disaster, why are Israel and Indonesia taking part in the Belt & Road Initiative? | |||

| A winning endgame rather than a strategy for “how not to lose” | Open war and surrender are unacceptable options. Justice Carpio’s preferred “third option” — which puts all its faith on the US-PH Mutual Defense treaty, without a proper assessment of how that treaty really works — actually lacks a meaningful end-game, and is prescription for “how not to lose” rather than a proper strategy for winning.

To achieve what Carpio wants to do, Duterte’s “4th option” needs to be given the leeway to work. The goal of the 4th option is to give China a incentive to respect Philippine law and obey Philippine instructions. That incentive is based on the threat of financial retaliation — not military force. |

|||

| Responding to Chinese aggression | A thought exercise about how to respond to China in a future conflict | |||

| Trade War (TW) | Punishing China economically | |||

| Military Action (MA) | Understanding what it REALLY takes to have our allies commit to the Philippine cause. Duterte’s “4th option” needs to happen before Carpio’s “3rd option” |

The DND’s P25B “credit card” for the AFP Modernization Program

Monday , 8, January 2018 AFP modernization Leave a commentThe Department of Budget & Management released the official AFP Modernization Budget for 2018: P25B. This represents a fraction of the total DND budget of P149.7B — which includes everything from salaries, to veterans pension payments, to operational expenses that keep aircraft flying, ships sailing, and guns firing.

When evaluating whether or not the P25B modernization budget is sufficient to cover the various pending and ongoing acquisition projects of the AFP (see here), one must first recall a little understood — but game-changing development — known as the Multi-Year Obligational Authority (MYOA) that was first implemented in the latter half of 2010. (See here).

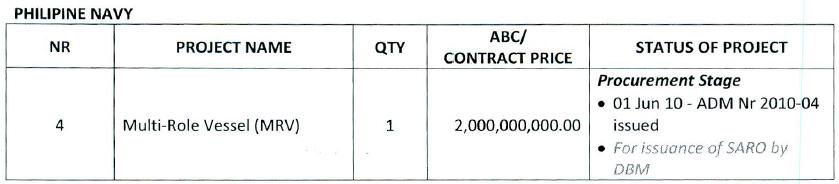

The MYOA was first used for the aborted Arroyo-era Multi-Role Vessel (MRV), which was then rebranded in the Aquino administration as the “Strategic Support Vessel” (re-using the name of the another Arroyo-era project that was originally based on a second-hand Japanese RO-RO vessel that eventually went nowhere). Since then, the MYOAs have been used for projects such as the Long Range Patrol Aircraft and the Close Air Support Aircraft.

The MYOA is significant because it unshackles the AFP from the limits of the national budget. It does so by using a simple concept that the average Filipino — who has ever made large consumer purchase (e.g., a car, a house, a refrigerator, or even a karaoke machine) — uses to buy what he or she needs while staying within the constraints of the household budget: “payments by installment”. The MYOA is essentially credit card for the department that uses it — to include the DND.

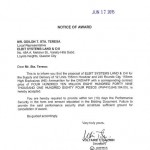

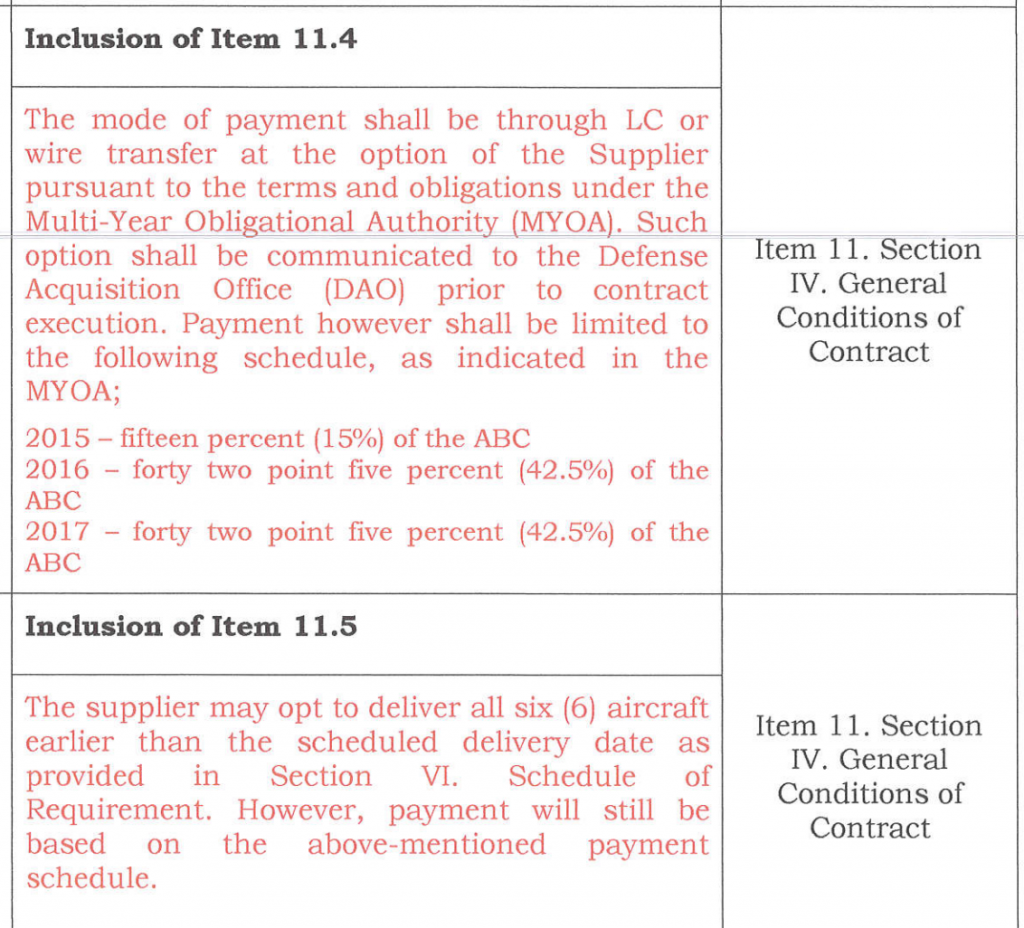

Consider for the example the Close Air Support Aircraft project which is valued at 4,968,000,000. The MYOA document for the project actually breaks the project into the following annual installments: Year 1: 15%, Year 2: 42.5%, Year 3: 42.5%.

|

While the original breakdown was pegged in 2016, and the actual contract signing didn’t take place till 2 year after, the breakdown formula shown above is comparable to how other projects were calculated, such as the still-pending Long Range Patrol Aircraft project.

Therefore for the first year, the funds required for the CASA project will only be approximately P754M. When applied the P25B annual budget, this would still leave P24.3B for other purchases.

If other projects also use the MYOA concept for their purchases . . .

. . . then instead of looking at the total Authorized Budgets for Contract of each purchase as the total the DND needs each year as its budget

. . . one only need to look at the percentage of the initial installment as the budgetary requirement for each year.

Furthermore modernization funds are NOT actually just limited to the General Appropriations Act. As per Section 6 of the Revised AFP Modernization Program, funds for the acquisition of AFP equipment is actually drawn from the AFP Modernization Trust Fund (AFPMTF). The AFPMTF sources funds from the following sources:

- The National Budget, particularly appropriations for the AFP Modernization

- Income from the Government Arsenal (once it being production for export)

- Sale of DND property

- Income from Public-Private partnerships

- Sale of excess defense articles and other uneconomically repairable equipment

- Funds from budgetary surplus

- Donations from local and foreign sources (this is how the AFP gets funding from Malampaya)

In summary, the MYOA facility, and the flexible funding nature of the AFP Modernization Trust Fund means that the size of AFP Modernization budget is does not actually limit what the AFP can do, as it did in the years before 2010. Even if the AFP were limited to the national budget as its source of funding, the P25B allocation — if done right — would simply represent the installment payment for that year. Thus, there remains much cause for optimism in the coming year, and the years ahead.

2017: What’s happening with the AFP modernization?

Saturday , 23, December 2017 AFP modernization Leave a commentWhile this is the first full year of the Duterte administration, many of the projects completed this year actually had their genesis in either the Arroyo or Aquino administrations. Among the capabilities that the AFP acquired this year are:

- Additional supersonic assets

- Continued increase in cargo transport capability, both by air and sea

- Situational awareness assets (e.g., radars, etc.)

- Armored, night-fighting-capable, mobility for mechanized troops

To give a more complete view of the state of the modernization program, this year’s article is divided into the following sections, presented here in reverse order:

- Pending acquisitions – these are acquisitions that have been publicly announced, either in conventional media or on the DND Website, that are still in various stages of completion. These include projects for which Special Allotment Release Orders (SARO) have been issued. Some are still awaiting results of bids or re-bids. Notable examples of projects in this state are the Philippine Navy Frigate and Combat Utility Helicopter (CUH) projects.

- Awaiting delivery – these are are projects for which the acquisitions have reached the “Notice to Proceed” stage and are in the process of being built from scratch, or are currently undergoing mandatory refurbishment, and have yet to be formally turned over to the AFP for operational use. Notable examples of this category are the long-delayed CN-212 light-lift aircraft that have been photographed in-hangar for months now, but have still not been delivered, and recently-awarded Close Air Support Aircraft project that has been awarded to Embraer.

- Acquisition list – these are items that are officially in the possession of the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

- Diversified sourcing – these are controversial equipment drawn from non-traditional sources and are in the process of being assimilated into the Table of Organization & Equipment.

In addition to the various official acquisitions:

- South Korea has committed to providing the Philippines with one surplus Pohang Class corvette (see here). To this date, details of this project have not been firmed up.

- The reported 24 additional Attack Helicopters has been omitted from this list. For more about this development, see here.

Discuss this article on the DRP forum here: http://defenseph.net/drp/index.php?topic=108.msg8934#msg8934

Companion discussion on the DRP forum Facebook extension here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/rpdefense/permalink/1532038013548707/

Diversified sourcing

This year also marked the first deliveries of equipment from non-traditional sources as part of the administration’s controversial balancing act between traditional allies and regional rivals.

Chinese weapons

A variety of Chinese firearms were donated to the Philippines as part of China’s fence-mending initiatives in the post-Aquino era in July 2017. However, contrary to initial reports about these donations being given to the AFP, these weapons were actually donated to the Philippine National Police.

Russian weapons

Efforts to foster closer ties between the Russian Federation and the Philippines bore fruit on on October 25, 2017 when the guided missile destroyer Admiral Panteleyev delivered a shipment of 5,000 assault rifles, one-million rounds of ammunition, 20 army trucks, and 5,000 steel helmets. The process of assimilating these equipment into the AFP is ongoing. Photos below are care of Inquirer.net particularly Nestor Corrales.

|

|

Note: This article is also available on the DefensePH.net forum on the long standing What’s happening with the AFP Transformation Roadmap / Modernization Program thread that’s been documenting the progress of the up-arming effort since 2003.

The acquisition list

The following list focuses on actual deliveries of equipment that were made in 2017.

|

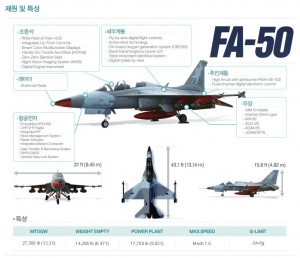

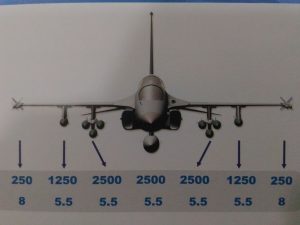

Surface Attack Aircraft / Lead-In Fighter Trainer |  |

FA-50PH deliveries were completed in May of this year, bringing the SAA/LIFT fleet to 12 aircraft. See DefensePH discussion here. Photo c/o PAF.

A number of these aircraft were used in combat against ISIS sympathizers in Butig in January of this year, and more prominently — and more openly — in the Battle for Marawi in June. This earned the Philippines the distinction of being the first country to use these South Korean aircraft in anger.

Note: In June, a self-described anti-corruption group filed a complaint with the ombudsman alleging the FA-50 actually lacked combat capability. This, however, was before the AFP revealed that it had quietly acquired precision guided munitions for which the FA-50 perfectly suited to use. |

||||||||||||||||||

| Cessna 208 |  |

The Philippine Air Force received two Intelligence, Surveillance & Reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft from the US on July 28, 2017. These aircraft were assigned to the 300th Air Intelligence and Security Group (300 AISG). See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| AIM-9 Sidewinder | The SAA-LIFT Munitions acquisition project has been divided into multiple lots. The DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order (SARO) on August 8, 2017 for Lot 1 worth P1,016,787,204.00. On December 29, Public Affairs Officer Arsenio Andolong announced that a Notice to Proceed was issued to Diehl Raytheon of Germany for the missiles on August 31, 2017, and that the contract had already been signed. See here. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| AGM-65 Maverick |  |

This is a component of the SAA/LIFT munitions project. The PAF revealed the existence of AGM-65 Maverick training rounds during the 70th PAF anniversary. The PAF has yet to officially confirm the existence of live equivalents. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Air defense radar acquisition project |  |

Situational awareness capabioity is a matter that the Philippine Air Force refuses to discuss openly. Periodically, however, it will provide “bread crumbs” that enthusiasts can leverage. A PAF sanctioned video showed a video of the EL/M-2288 AD-STAR radar, thus confirming a SIPRI.org report that indicated that the PAF was already in possession of this equipment. A notice of award for the project was issued in January 2016 to the Israeli company Elbit. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Elbit ELM-2106NG |  |

Situational awareness capability is a matter that the Philippine Air Force refuses to discuss openly. So while select members of the DefensePH / Timawa community have been aware of these Israeli-made mobile radar units for some time, Operational Security (OPSEC) considerations these have hitherto kept them out of forum discussions. However, an editing oversight included a photograph of this radar unit on an official PAF publication. Additional details are for the PAF PIO to explain. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Squad Designated Marksman Rifle & Mid-length Carbines |  |

PAF receives 50 upgraded rifles on February 28, 2017. Forty-six (46) were in the form of 5.56mm Mid-length Carbines with Aim-point optics, and 4 were Squad Designated Marksman Rifles with ACOG sights. | |||||||||||||||||||

|

BRP Davao del Sur (LD-602) |  |

The second Tarlac class Strategic Support Vessel was launched on September 29, 2016 at the PT PAL shipyard in Indonesia and christened the BRP Davao del Sur. It arrived at the Port of Manila on the 7th of May and was commissioned on May 10. See here. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Multipurpose Assault Craft (MPAC) Mk.3 |  |

The three Mk.3 MPACs were slated to be the first missile-equipped vessels in the Philippine Navy. These were unveiled — without the Rafael Spike missiles they were designed to carry — on the 119th Anniversary of the Philippine Navy on May 22, 2017. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Cessna TC-90 |  |

The Philippine Air Force initially leased five Cessna TC-90 aircraft from Japan for use as interim maritime patrol aircraft (see here). The first of 3 batches of PAF aircrews arrived in Japan for training in December 2016. As per PAF press releases, the training syllabus included 90 hours of ground and 170 hours of flight training. The first two aircraft arrived on March 26, 2017. The DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order for this project in May 31, 2017 worth P155,066,057.00. Later in October, Japan announced that it was converting the lease into a donation. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Tethered Aerostat Radar System (TARS) |  |

The Joint U.S. Military Assistance Group in the Philippines, formally transferred a 28M Class Tethered Aerostat Radar System (TARS) on August 22, 2017. The 28M Class TARS is a self-sustained, rapidly deployable, unmanned lighter-than-air platform which can rise to an altitude of 5,000 feet while tethered by a single cable. Photo c/o US embassy. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Marine Forces Imagery and Targeting Support Systems (MITSS) |  |

This P684.32M project sought to acquire 6 sets of Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, 9 sets of Target Acquisition Devices, and 12 kits of Tactical Sensor Integration Subsystems. Details here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| RQ-11B Raven |  |

On January 27, the Philippine Marines received three units of hand-launched RQ-11B Ravens and associated support equipment from the United States as part of a counter-terrorism grant. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ford F-550 trucks |  |

On July 7, the NAVSOG received 12 units of Ford F-550 trucks from JUSMAG for mobility purposes as well for transport Rigid Hull Inflatable Boats (RHIB) of the unit. Photo c/o US embassy. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Elbit Soltam 155mm Howitzer |  |

A Notice of Award for this project was issued to Elbit System on June 17, 2015 for 12 units to be issued to both the PA’ and PMC. Finally delivery of the final 9 units was made on July 17, 2017. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| M134D gatling guns |  |

JUSMAG turned over a variety of anti-terror equipment to the PMC including four M-134D Gatling-style machine guns. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| M40A5 sniper rifles | On January 27, 2017, the Philippine Army and Marines received 85 units of M40A5 sniper rifles from the United States. See here. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| M-4 Carbine |  |

JUSMAG turned over a variety of anti-terror equipment to the PMC including 300 M-4 carbines. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Glock 21 pistols | JUSMAG turned over a variety of anti-terror equipment to the PMC including 200 Glock 21 pistols. See here. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| M203 grenade launchers |  |

JUSMAG turned over a variety of anti-terror equipment to the PMC including 100 M-203 rail mounted grenade launchers. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Rubber boats with outboard motors |  |

JUSMAG turned over a variety of anti-terror equipment to the PMC including 25 units of combat rubber raiding craft. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

|

RPG-7 Rocket Launcher acquisition |  |

The Bulgarian Arsenal won the bid to supply the AFP with RPG-7 rockets, thus satisfying the Rocket Launcher Acquisition Project that had been on various modernization reports since 2008. Six launchers and 800 rockets were available for use when the Battle of Marawi broke out. See here. | ||||||||||||||||||

| M-203 grenade launchers |  |

On January 27, the Philippine Army and Marines received 400 units of M-203 grenade launchers from the United States. See here. | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Initial & Final Forming Units and Bullet Assembly |

|

The GA took delivery of Initial Forming Unit (IFU) (250 ppm), Final Forming Unit (FFU) (250 ppm) & Bullet Assembly Machine (BAM) (125ppm) procured from Waterbury Farrel of Canada and delivered at the Case & Bullet Division in Bataan Plant on March 23, 2017. These machines will be used in the production of 5.56mm M855 bullets. |

In addition to acquisitions via bidding, South Korea has committed to providing the Philippines with one surplus Pohang Class corvette, and a landing craft. These and the aforementioned Korean acquisitions have yet to be delivered and have therefore been omitted from the list above.

Awaiting delivery

A significant number of high-profile projects remain pending, and have been omitted from the acquisition list. These are listed immediately below.

| Service | Ongoing projects | |||||||

|

Gozar Air Station – on January 16, 2017, the DND allocated supplemental funding for the implementation of Radar Basing Support System Project Lot 1 (Gozar Station). See here. |

|||||||

|

Anti-Submarine Helicopter Acquisition – Special Allotment Release Order (SARO) SARO-BMB-D-17-0006000, worth P4,559.198,336.00, was issued for this project on May 3, 2017. Agustawestland was the only company that qualified to take part in the bidding in November 2015. The DND announced in January that post-qualification of the company and its offering: AW-159 Wildcat. See here.

Spike ER / Spike NLOS – the AFP is awaiting delivery of Spike ER and Spike NLOS missiles from Israel. These are due to be used with the MPAC Mk.3 and incoming AW159 helicopters respectively. See here. ex-ROKN Mulkae class (LCU-78) – South Korea promised this EDA item in June 2014 and quietly delivered the boat in July 2015. A refit project costing P27,138,295.51 was approved for the vessel, but remains non-operational. Unverified reports suggest that the vessel might actually be Beyond Economical Repair (BER). See here. Amphibious Assault Vehicle (AAV) – Samsung Techwin was declared the lowest single calculated bidder for the P2.5B AAV project. Details here. 40mm automatic grenade launcher – the DND issued a Notice To Proceed (NTP) in favor of Advanced Material Engineer / ST Kinetics, represented locally be Floro International Corp, to supply and deliver eight (8) units of 40mm automatic grenade launchers for the contract price of P19,750,672.00 on March 4, 2014. Details here. 2 1/2 Ton Truck Troop Carrier & Wrecker – Notice to Proceed was issued to Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency for the acquisition of 227 units of 2 1/2 Ton Truck Troop Carrier and 10 units of 2 1/2 Ton Wrecker at the cost of P1,419,821,000.00 for the Philippine Marine Corps on October 18, 2017. See here. 1 1/4 ton Truck Troop Carrier – Notice to Proceed was issued to the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency for the acquisition for 108 units of 1 1/4 ton Truck Troop Carrier, worth P313,956,000.00 for the Philippine Marine Corps on October 18, 2017. See here. |

|||||||

|

KM-450 1/4-ton truck acquisition – on October 19, 2015, the DND issued a Notice to Proceed to Kia motors for the supply of 717 trucks to the Philippine Army. See here.

KM-451 ambulance acquisition – on October 19, 2015, the DND issued a Notice to Proceed to Kia motors for the supply of 60 units of Field Ambulances to the Philippine Army. See here. Force protection equipment – Notice to Proceed was issued to MKU Limited for the acquisition of 3,480 units of Force Protection Equipment at a contract price of P120,435,000.00 on April 17, 2017. A rival company, U.M. Merkata DOO was initially declared the Lowest Calculated Bidder, but was unable to pass Post Qualification, leading to the award to the 2nd LCB. See here. Tactical Engagement Simulation System (TESS) – the DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order (SARO) worth P52,251,959.00 for the purchase of the Tactical Engagement Simulation System Acquisition Project on May 29, 2017. A Notice to Proceed in favor of SD Systems Co., Ltd, Ziwoo Information & Technology, Inc, and AR Vision Inc. was issued on September 2017. See here. |

|||||||

|

ScanEagle UAS – a Janes.com article reported a pending follow-on purchase of 6 additional Insitu Scan Eagle Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) for the AFP. This confirmed that an undisclosed number of these aircraft were already in Philippine service. See here.

Civil Engineering Equipment Acquisition Project – the DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order worth P150,315,000.00 to fund Lot 3 of the Civil Engineering Equipment Acquisition Project. Lot 3 consisted of 32 units of 5-ton dump trucks and 3 units of 20-ton dump trucks. A notice of award was issued to Hino Motors Philippines for this project on Juney 14, 2017. See here. |

|||||||

|

|

Pending acquisitions

A significant number of high-profile projects remain pending, and have been omitted from the acquisition list at the bottom of this article. These are listed immediately below.

| Service | Pending projects | |

|

Long Range Patrol Aircraft acquisition project – the previous bid for this project was closed in July due to disqualification of all bidders. A new bid was opened in September. See here.

Combat Utility Helicopter (CUH) – on December 20, 2017, the DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order (SARO) worth P12,073,122,578.00 was issued to fund the acquisition of 16 Combat Utility Helicopters. The SARO, however, did not identify the specific model selected. But in the recent past, the PAF acquired the W-3 Sokol and Bell 412 for its CUH requirements. Details here. SAA/LIFT munitions – the ordnance that SAA-LIFT aircraft will carry are being acquired via a separate acquisition project. These include Air-to-Air Missiles (312 Pieces), Air-to-Surface Missiles (125 Pieces), 20mm ammo (93,600 Pieces), and Chaffs/IR Flares. A SARO for Lot 2 worth 3,292,926,550.00 was released June 20, 2017, and another for Lot 1 worth P1,016,787,204.00 was released on August 8, 2017. A Timawan / DefensePH shoulder-tap hinted at the selection of AIM-9L Sidewinder missiles for the air-to-air missile component. Inert versions of the AGM-65 Maverick were revealed during the 70th PAF anniversary thus identifying the Air-to-Surface component of the package. Details here. See also the following thread: Teddy Locsin: Letting the cat out of the bag re the SAA/LIFT Munitions project? Miscellaneous PAF munitions – the DND issued SARO-BMB-D-17-0010323 which released P267,888,300.00 for the acquisition of “air munitions”. The SARO gave no additional details about this acquisition, which was issued in July 12, 2017. Another SARO (SARO-BMB-D-17-0011782) worth P312,077,200.00 was used to acquire “special munitions”. See here. Full-motion flight simulator (FA-50) – in 2014, the DND announced the opening of a P246M project to acquire a full-motion simulator for for the FA-50 SAA/LIFT aircraft of the Philippine Air Force. On August 17, 2017, the DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order worth 362,904,800.00 for the acquisition of the FA-50 simulator with Integrated Logistics Support (ILS). See here. Full motion flight simulator – in June 2017, the PAF issued a bid invitation for the construction of a full-motion flight simulator worth P13,879,340.00. See here. FA-50 ComSec requirements – on September 8, 2017, the DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order (SARO) worth P53,350,000.00 for FA-50PH ComSec Requirements. See here. |

|

|

Frigate Acquisition Program – this P18B project seeks to acquire two brand new multi-role frigates in a complicated two-stage bidding process. Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers Ltd of India was initially declared the Lowest Calculated Bidder. However they were rejected during Post Qualification due to concerns about the bidder’s financial capacity and ability to implement the order. The contract was eventually awarded to Hyundai Heavy Industries. Details here.

Flag-level politics surrounding this acquisition broke onto the national spotlight with the unceremonious relief of the Philippine Navy Flag Officer in Command (FOIC). See here. Multi-Purpose Assault Craft (MPAC) – on December 15, 2017, the DND issued a Special Alottment Release Order (SARO) worth P269,799,999.99 for the acquisition of three (3) additional Multi-Purpose Assault Craft for the Philippine Navy. As of writing, it is unclear which of the three existing MPAC models this batch would be based upon. See here. AN/SPS-77 Sea Giraffe 3D Air Search Radars for the GDP class frigates – on December 14, 2016, the US State department approved the sale of two AN/SPS-77 Sea Giraffe, explicitly, for use on two ex-Hamilton class cutters in PN service. See here. Jacinto Class Patrol Vessel Upgrade Phase 3 – this project sought to upgrade the weapons and electro-optical systems of all three ships of the class. See here. Jacinto Class Patrol Vessel Upgrade Phase 2 – this is a sought, among other things, to overhaul and improve the main propulsion system, electrical, and various auxiliary systems of BRP Artemio Ricarte (PS-37). Other members of the class had already been upgraded to this standard. See here.

|

|

|

Shore-Based Missile System – arguably, the AFP modernization controversy of the past year was the deferral of the Philippine Army’s Shore-Based Missile System (SBMS) to an as yet undisclosed “horizon” of the AFP Modernization Program. This was discussed on the DefensePH forum on the following thread. Funds for the P6.5B project — which originally became public in 2011 and — were realigned to acquire force-protection equipment instead. It was a stunning reversal of a territorial defense initiative that drew boisterous condemnation on defense social media and earned the Chief of Staff AFP, General Hernando Iriberri, the monicker “General Helmet”.

M113A2 Firepower Upgrade project – on November 28, 2017, the DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order (SARO) worth P1,051,650,000.01 for the “Firepower Upgrade of M113A2” project of the Philippine Army. See here. Thermal sights and cameras – on November 23, 2016, the DND issued bid documents for a P240M acquisition of thermal optical sights and thermal camera. On September 18, 2017, the DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order (SARO) worth P136,809,543.00 for this project.See here. 60mm Mortar Acquisition project – 150 mortars are being acquired. Details here. Ballistic helmet (standard & special operations) – the DND issued a bid invitation worth P1,189,605,000.00 for standard and special operations ballistic helmets on November 22, 2017. See here. 0.50 cal Machine Gun Red Dot Sight System – the DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order, in favor of the Philippine Army, worth P80M to cover the procurement of a .50 Cal Machine Gun Red Dot Sight System. See here. |

|

|

Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) Equip’t (Lot 1) – on November 16, 2017, the DND issued two Special Allotment Release Orders (SARO) with a combined value of P109,569,777.00 for the Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) Equipment Acquisition Project (Lot 1). See here.

Pag-asa Island Beaching Ramp – responding the President’s instructions on April 6, 2017 to improve facilities in KIG, SND Lorenzana conducted a personal tour of facilities on Pagasa Island on April 21, 2017 an announced a plan to improve Rancudo Airfield and to build a long-awaited beaching ramp to facilitate the offloading of cargo. On June 6, the DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order (SARO) worth P231,272,837.00 for the construction of the beaching ramp. According to Defense spokespoerson Arsenio Andolong, the ramp is scheduled to be completed in “early 2018”. See here. Marine Intelligence Acquisition Project – the DND issued a Special Allotment Release Order worth 73,537,500.06 for a “Maritime Intelligence (MARINT) acquisition project” on June 8, 2017. See here. |

|

|

Indigenous assault rifle production – the Government Arsenal is in advanced negotiations with ST Motive of South Korea to acquire equipment for local manufacture of assault rifles based on the M-16/M-4 design. Similar arrangements with other manufacturers, such as Colt’s Manufacturing Company are also being explored, but none are as advanced at ST Motive. |

Related articles:

2016: What happening with the AFP modernization program

2015: What’s happening with the AFP modernization program

2014: What’s happening with the AFP modernization program

2013: What’s happening with the AFP modernization program

2012: What’s happening in the AFP capability upgrade program

2016: What’s happening with the AFP Modernization

Sunday , 1, January 2017 AFP modernization Leave a commentThe year 2016 delivered the last of the Aquino administration’s contributions to the AFP modernization effort. While many had their genesis during the Arroyo administration, credit for continuation and eventual completion of these projects can — within reason — be attributed to BSA III. As with 2015, this year continued the trend towards high-value, capability-leap-frogging, acquisitions for all three services.

Among the capabilities that the AFP acquired this year are:

- Additional supersonic assets

- Continued increase in cargo transport capability, both by air and sea

- Armored, night-fighting-capable, mobility for mechanized troops

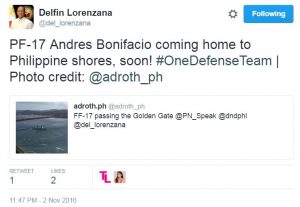

Among the highlights for the year was the transit of the Philippine Navy’s latest frigate past the iconic Golden Gate bridge, as it made its way from Coast Guard Island in Alameda to the Philippines.

|

|

|

| BRP Andres Bonifacio (FF-17) crossing the Golden Gate bridge. A DefensePH.net exclusive photo | SND Delfin Lorenzana tweeting about the FF-17 photo |

To give a more complete view of the state of the modernization program, this year’s article is divided into the following sections, presented here in reverse order:

- Pending acquisitions – these are acquisitions that have been publicly announced, either in conventional media or on the DND Website, that are still in various stages of completion. Some are still awaiting results of bids or re-bids. Others have had Notices to Proceed (NTP) to issued. Notable examples of projects in this state are the the Philippine Navy Frigate and yet-again-restarted Close Air Support Aircraft projects.

- Awaiting delivery – these are are projects for which the acquisitions are in the process of being built from scratch, or are currently undergoing mandatory refurbishment, and have yet to be formally turned over to the AFP for operational use. Notable examples of acquisitions in this state would be the Strategic Sealift Vessel, which is currently undergoing trials in Indonesia and the ex-ROKN Mulkae class LCU, which is already in the Philippines, but is still awaiting refurbishment before it can be commissioned into service.

- Acquisition list – these are items that are officially in the possession of the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

In addition to the various official acquisitions, South Korea has committed to providing the Philippines with one surplus Pohang Class corvette (see here). To this date, details of this project have not been firmed up. It is unclear if this project will materialize.

Note: This article is also available on the DefensePH.net forum on the long standing What’s happening with the AFP Transformation Roadmap / Modernization Program thread that’s been documenting the progress of the up-arming effort since 2003.

The acquisition list

The following list focuses on actual deliveries of equipment that were made in 2016.

|

Surface Attack Aircraft / Lead-In Fighter Trainer |  |

The second batch of two FA-50PH aircraft, #003 and #004, arrived from South Korea, via Taiwan, at 1130H on December 1, 2016 . FA-50PH #002 suffered Foreign Object Damage (FOD) to its engine grounding the aircraft for most of 2016, but a replacement engine was acquired in time to allow it and FA-50 #001 to escort their newer bretheren upon their arrival. See DefensePH discussion here. | ||

| C-130T acquisition |  |

The second C-130T (#5040) Hercules acquired from the United States as EDA arrived at 7:56 p.m on October 10, 2016 at Benito Ebuen AFB in Mactan, Cebu. The photograph on the left shows the aircraft enroute to the Philippines at an air base in Southern California. See DefensePH discussion here. | |||

| UH-1 upgrade program |  |

Four (4) UH-1 Iroquois helicopters, with upgraded engines, tail boom strake, and fast fin, were commissioned into PAF service on January 20, 2016. Photograph c/o Philippine Air Force | |||

|

BRP Tarlac (LD-601) |  |

The first Strategic Support Vessel built in PT PAL (Indonesia) was launched as the BRP Tarlac (LD-601) on January 18, 2016, and arrived in Manila on May 16, 2016. The ships of the Tarlac class are the largest combat vessels in Philippine Navy history. See here for the DefensePH discussion on this ship.

See the construction timeline for this ship here. |

||

| BRP Andres Bonifacio (FF-17) |  |

The US government sold the ex-USCGC Boutwell to the Philippine government on July 21, 2016 as part of the Excess Defense Article (EDA) program. It sailed for the Philippines on November 1, 2016 and arrived at Pier 13 of Manila South Harbor on December the 9th. Incidentally, the first crew of the BRP Gregorio del Pilar, previously the USCGC Hamilton, served on board the Boutwell as part of their training for accepting the PN’s first Hamilton class WHEC. See here. | |||

| BRP Gregorio Velasquez (AGR-702) |  |

The research vessel R/V Melville was transferred to the Philippine Navy on April 29, 2016, arrived on ____, and named after Dr. Gregorio Velasquez — the father of Philippine Phycology, the study of algae. See DefensePH discussion here. | |||

|

The Australian government donated HMAS Brunei and HMAS Tarakan, members of the Balikpapaan class Landing Craft Heavy (LCH), which eventually became BRP Ivatan and BRP Batak respectively. The Philippine Navy then acquired the remainder of the class and commissioned them on May 30 as the BRP Agta, BRP Iwak, and BRP Waray. | ||||

|

Elbit UT-25 RCWS |  |

Select M-113s, that the LAD received last year, were up-armed with Elbit systems, thermal imager equipped, 25mm Unmanned Turret (UT-25). See here. | ||

| Rubber tracks |  |

LAD started fielding one-piece rubber tracks manufactured by Soucy Defense in their M-113-based vehicles. See here. | |||

| Battle Dress Uniform |  |

The Philippine Army issued a new Battle Dress Uniform (BDU) developed by a Canadian manufacturer. See here. | |||

|

Rotary Ammo Loading Machine |  |

The GA commissioned its first rotary loading machines which were acquired from the Vasini Corporation (Italy). These are slated to increase production by 25 million rounds, bringing the Arsenal’s total annual production to 75 million rounds. See here. | ||

| Laser etching machine |  |

The photo on the left shows GA staff inspecting a laser etching machine that was eventually delivered to GA on August 25, 2016. With completion of the P35M acquisition, the GA gained the ability to place serial numbers on EACH individual cartridge it produces and then package them in 30-round cartons which will then be bar coded. This acquisition was designed to facilitate accounting and traceability of ammunition. This was a good governance measure undertaken in light of past controversy over AFP ammunition being found in the hands of enemies of the state. See here. | |||

| Philippine Navy SDMR & MSSR |  |

On October 27, 2016, the Philippine Navy received 36 refurbished and upgraded rifles. Ten units were in Squad Designated Marksman Rifle (SDMR) configuration w/ trijicon optical sight. Another 10 units were in Marine Scout Sniper Rifle (MSSR) Gen5 configuration with AAC sound suppressors. The remaining 16 units were in MSSR Gen-4 w/ AAC sound suppressors. See here.

Four sets of MSSR Gen 4 were delivered in May 20, 2016. |

|||

| AFP JSOG SDMR |  |

AFP JSOG submitted 46 unserviceable rifles to the GA on May 27, 2015. These units were refurbished to Squad Designated Marksman Rifle standard, with 5 units being equipped with advanced combat optics and low-profile gas block. They were returned to JSOG on October 19, 2016. See here. | |||

| M249 refurbishment program |  |

The Government Arsenal undertook refurbishment of 5 M249 Squad Automatic Weapons. These machine guns were part of the first acquisition under the AFP Modernization Program in 2003. See here. |

In addition to acquisitions via bidding, South Korea has committed to providing the Philippines with one surplus Pohang Class corvette, a landing craft, and several rubber boats. These and the aforementioned Korean acquisitions have yet to be delivered and have therefore been omitted from the list above.

Awaiting delivery

A significant number of high-profile projects remain pending, and have been omitted from the acquisition list. These are listed immediately below.

| Service | Ongoing projects | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

ex-ROKN Mulkae class (LCU-78) – South Korea promised this EDA item in June 2014 and quietly delivered the boat in July 2015. A refit project costing P27,138,295.51 was approved for the vessel, but remains non-operational. Unverified reports suggest that the vessel might actually be Beyond Economical Repair (BER). See here. Amphibious Assault Vehicle (AAV) – Samsung Techwin was declared the lowest single calculated bidder for the P2.5B AAV project. Details here.

|

|||||||

|

Rocket Launcher Light Acquisition Project – Airtronic USA, Inc. was selected to supply 400 US-made RPG7 rocket launchers, and associated 40mm rockets, as part of a Foreign Military Sale (FMS) deal. While components of this deal have reportedly been delivered, the remainder remain obscure. For that reason, this project remains listed as “awaiting arrival. See here |

|||||||

|

|

Pending acquisitions

A significant number of high-profile projects remain pending, and have been omitted from the acquisition list at the bottom of this article. These are listed immediately below.

| Service | Pending projects | |

|

Long Range Patrol Aircraft acquisition project – the PAF issued an invitation to the 2nd-stage bidding for this project in October, 2016. See here. It is worth noting that the PAF is due to receive 5 leased TC-90 aircraft from Japan for use in maritime patrol. How this lease arrangement affects the long-standing LRPA project is uncertain.

Close Air Support Aircraft acquisition project – the bid for this project failed for the second time in December 2015. However, instead of proceeding with a negotiated procurement as per the IRR of RA9184, a third bid was announced in October 2016. See here. AN/SPS-77 Sea Giraffe 3D Air Search Radars for the GDP class frigates – on December 14, 2016, the US State department approved the sale of two AN/SPS-77 Sea Giraffe, explicitly, for use on two ex-Hamilton class cutters in PN service. See here. Air defense radar acquisition project – like the SAA/LIFT project, this P2.68B acquisition is part of the PAF’s systems approach to reviving the country’s ability to enforce the Philippine Air Defense Identification Zone (PADIZ). A notice of award for the project was issued in January 2016 to the Israeli company Elbit. See details here. SAA/LIFT munitions – the ordnance that SAA-LIFT aircraft will carry are being acquired via a separate acquisition project. These include Air-to-Air Missiles (312 Pieces), Air-to-Surface Missiles (125 Pieces), 20mm ammo (93,600 Pieces), and Chaffs/IR Flares. Details here. See also the following thread: Teddy Locsin: Letting the cat out of the bag re the SAA/LIFT Munitions project? |

|

|

Frigate Acquisition Program – this P18B project seeks to acquire two brand new multi-role frigates in a complicated two-stage bidding process. Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers Ltd of India was initially declared the Lowest Calculated Bidder. However they were rejected during Post Qualification due to concerns about the bidder’s financial capacity and ability to implement the order. The contract was eventually awarded to Hyundai Heavy Industries. Details here.

Anti-Submarine Helicopter Acquisition – Agustawestland was the only company that qualified to take part in the bidding in November 2015. The DND announced in January that post-qualification of the company and its offering: AW-159 Wildcat. See here. Jacinto Class Patrol Vessel Upgrade Phase 3 – this project sought to upgrade the weapons and electro-optical systems of all three ships of the class. See here. Jacinto Class Patrol Vessel Upgrade Phase 2 – this is a sought, among other things, to overhaul and improve the main propulsion system, electrical, and various auxiliary systems of BRP Artemio Ricarte (PS-37). Other members of the class had already been upgraded to this standard. See here. Marine Forces Imagery and Targeting Support Systems (MITSS) – this P684.32M project sought to acquire 6 sets of Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, 9 sets of Target Acquisition Devices, and 12 kits of Tactical Sensor Integration Subsystems. Details here. 40mm automatic grenade launcher – the DND issued a Notice To Proceed (NTP) in favor of Advanced Material Engineer / ST Kinetics, represented locally be Floro International Corp, to supply and deliver eight (8) units of 40mm automatic grenade launchers for the contract price of P19,750,672.00 on March 4, 2014. Details here. |

|

|

Shore-Based Missile System – arguably, the AFP modernization controversy of the year was the deferral of the Philippine Army’s Shore-Based Missile System (SBMS) to an as yet undisclosed “horizon” of the AFP Modernization Program. This was discussed on the DefensePH forum on the following thread. Funds for the P6.5B project — which originally became public in 2011 and — were realigned to acquire force-protection equipment instead. It was a stunning reversal of a territorial defense initiative that drew boisterous condemnation on defense social media and earned the Chief of Staff AFP, General Hernando Iriberri, the monicker “General Helmet”.

Thermal sights and cameras – on November 23, 2016, the DND issued bid documents for a P240M acquisition of thermal optical sights and thermal camera. See here. Tactical Engagement Simulation System (TESS) – on December 21, the DND issued bid documents for P80.4M acquisition of tactical simulation equipment. See here. 60mm Mortar Acquisition project – 150 mortars are being acquired. Details here. KM-450 1/4-ton truck acquisition – on October 19, 2015, the DND issued a Notice to Proceed to Kia motors for the supply of 717 trucks to the Philippine Army. See here. KM-451 ambulance acquisition – on October 19, 2015, the DND issued a Notice to Proceed to Kia motors for the supply of 60 units of Field Ambulances to the Philippine Army. See here. |

|

|

Indigenous assault rifle production – the Government Arsenal is in advanced negotiations with ST Motive of South Korea to acquire equipment for local manufacture of assault rifles based on the M-16/M-4 design. Similar arrangements with other manufacturers, such as Colt’s Manufacturing Company are also being explored, but none are as advanced at ST Motive. |

Related articles:

2015: What’s happening with the AFP modernization program

2014: What’s happening with the AFP modernization program

2013: What’s happening with the AFP modernization program

2012: What’s happening in the AFP capability upgrade program

AFP was a user of Chinese equipment long before Duterte

Monday , 19, September 2016 AFP modernization, Air Force, Army, Philippine Navy Leave a commentThe 48th anniversary of the 250th Presidential Airlift Wing, on the 13th of September, 2016, gave President Duterte’s critics yet another treasure-trove of “Duterteisms” that have since become fodder for punditry on defense social media and even generated international interest in Philippine foreign policy. In this latest episode, Duterte stated, among other controversial assertions, his openness towards equipment AFP equipment from China and Russia.

While its worth noting that in a separate speech in Cebu, President Duterte also mentioned interest in sourcing equipment from Israel, indicating a policy of broadened equipment sourcing beyond traditional sources, critics — and numerous media articles — focused on the “China” aspect of the discussion.

The prospect of Chinese weapons complicating the AFP’s logistics picture with equipment that are incompatible with the existing Western-oriented support infrastructure is cause for legitimate concern. Should Sino-PH tension escalate, Chinese equipment could very well be subjected to a spare-parts embargo. Other than being part of an “unconventional warfare” operation, use of a potential opponent’s weapons also introduces operational security (OPSEC) risks because the opposing force knows as much about weapon’s capabilities as the user — if not more so.

These risks however, arguably, are not lost upon AFP planners, and the chain of command. Sourcing equipment from China is not, in fact, new and have hitherto been restricted to non-kinetic equipment. It is actually very likely that all we will see will simply be more of the same.

The following Philippine Star article from May 27, 2007 relates one instance where the PRC offered assistance to the AFP:

DND seeks more military aid from China

Updated May 29, 2007 – 12:00amThe Department of National Defense (DND) has called for sustained defense and training exchanges with China, including military aid, following a security cooperation dialogue between the two countries last week.

Defense Undersecretary Antonio Santos relayed this message to Lt. Gen. Zhang Qinsheng, deputy chief of staff of the People’s Liberation Army, who led the Chinese delegation to the 3rd Annual RP-China security cooperation conference at Camp Aguinaldo in Quezon City Friday.

. . .

On top of allowing Filipino troops to undergo military schooling in Beijing, the Chinese government donated heavy military engineering and medical equipment to the Armed Forces of the Philippines last year. – Jaime Laude

An Inquirer.net article on the same story presented the following photograph of the donation of PY165H graders and unidentified bulldozers.

|

Since then, these Chinese donated engineering equipment have been seen in the colors of all AFP services. Photographs are care of various Timawans.

|

|

|

||

| Philippine Navy | Philippine Air Force | Philippine Army |

Exactly what Chinese equipment Duterte is prepared to acquire for the AFP is unclear. What is certain, however, is that the potential equipment that can be had from China is as broad as its manufacturing base. Such equipment need not even be military in nature.

Why 5.56mm sniping rifles for the AFP?

Saturday , 10, September 2016 Army, Philippine Army, Philippine Navy Leave a commentOn August 21, 2006 the Timawa forum saw a discussion between a Philippine Marine Colonel (MBLT6) and a Singaporean Army Major (Shingen) about sniper rifles an engagement distances in the the Philippine setting. The end result was a glowing response from Shingen as follows:

This is one of the best post, or not the best post i have seen so far in this forum. Thank you so much for clarifiying things, all your examples are very clear and informative, especially no. 3. Would add this to my scrapbook and use it as material if required back camp.

This accolade elevated this discussion to a “reference thread” which moderators took special care in keeping troll free.

|

|

|

| Marine Scout Sniper Rifle (5.56mm) | Barret (12.7mm / .50 cal) |

In an effort to preserve this discussion from database crashes and similar incidents, this section the following thread has been replicated here:

First, lets define terms. The term primary sniper rifle refers to primary range. Our (Marine Corps) doctrine requires three types of sniper rifles ie., primary range (max 600m for company level) , intermediate range ( 800m max and a Bn organic) and long range (1000m and a Brigade organic). We practice combined arms concepts which means higher units may attach thier organic units to subordinates in order to tailor fit their capabilities to the environment they are operating in and the threats they are facing. secondly, the term sniper rifle does not dictate on the caliber. Its defined as a rifle with a scope accurized with high quality parts (match grade) and uses match grade ammunition. The 5.56mm round in the MSSR qualifies per our doctrines and international definition.

Why have 3 types of sniper rifles? Based on our experience in battling communist, muslim seperatist and military adventurism for 30+ years in different terrains in the Philippines. We had learned that under different sniping conditions the characteristics of a type of sniper rifle has its pros and cons.

Example 1. a sniper stalks his prey that requires moving at the least observation by the enemy the reason he has to be a master of camoflauge to avoid detection. It will be diffucult to crawl with a cal 50 barret. The MSSR will be a favorite in this conditions.

Example 2: The MSSR or primary range rifle is the king of 600m engagements simply due to lesser recoil. It accounted most of the kills in our year 2000 campaign in central mindanao. Why? against multiple targets and follow through shot in case of a miss nothing beats the 5.56mm round. the lesser recoil ensures target acquisition after recoil. We tested this with the equally accurisided M-21 7.62mm. each equally skilled sniper were required to shoot 6 poppers each and armed with the M21 and MSSR at 400m. The MSSR finished his 6th popper while the other was just starting to aim for his 3rd – FOV issues due to recoil i’m sure you know. Example 3: the cal 50 barret has the needed characteristics for longer range simply because of of its heavier 750 grain bullet which is less prone to that devil wind that all snipers fear. The MSSR cannot compete with this at longer range. But at shorter ranges below 600m the barret has distinct disadvantages. It has a louder sound report, flash and concussion (leaves/bushes moves) allowing easier detection and wow expect counter fire from the enemy. A sniper always ensures he is not detected please don’t do this in engaging the enemy with highly trained countersnipers. The barret is best in engagements at 1000m+ in a jungle environment if you can find one. the rule is more max at 400m. The MSSR has a an almost negligble flash an sound report. The 24 inch barrel has its advantages it ensures the total burning of the propellant before the bullet exits the muzzle hence lesser flash as well as higher velocity means lesser leads in moving targets – the 5.56mm round does have at least 250+ fps higher speed the the 7.62mm and cla 50 round – right?. longer barrels adds more velocity and having more range and lethality. and of course lesser concussion and sound report compared to the 7.62 and cal.50 round. the MSSR was adopted by us in 1996 and copied by the IDF and US in 2000 you are more than welcome to learn from our experiences.

I really had the same perceptions in my youth when I was a Lt 24 yrs ago. The macho 7.62mm or even the cal 30 (7.62mm x 54) M-1 garand round were superior in all aspects. But my experience change that with advancements in weapons technology as well as my combat and competition experience. I was amazed with the results of our 2000 year campaign as well as the success of the M-16 in the Service Rifle Competitions in Camp Perry,Ohio which since 1996 it had dominated the championships beating the favorites as the M-1A1 and military versions M-14 rifles. We in the Marine Corps have the only existing sniper school in the Philippines since 1967. We load our own match ammo for 5.56mm and 7.62mm in 69 grain Sierra BTHP match, 75 grain Hornady and 168 grain Sierra in 7.62mm BTHP match as well as subsonic rounds for both calibers for use in our Night Fighting Weapon System. Don’t know if there are existing sniper schools in other in southeast asian countries. And please no more lethality issues – shot placement at 600m is not an issue for the MSSR our snipers are trained to hit head shots at 600m and even a cal .22LR at shorter distances can ensure that kill. I’ve seen that – we operate in the most volatile region in Southeast Asia.

How are “special units” in the AFP different from each other?

Saturday , 10, September 2016 Army, Philippine Navy Leave a commentAt one point or another, military enthusiasts ask this question. Typically in relation to discussions that dwell on the ascendancy of one special unit versus another. “Who is more elite?” When faced with such queries, professional often point out there each special unit is trained for a specific task and require individuals suited for such tasks. That does not inherently make them better than anyone else.

To put things in perspective, the author put together the following summary to differentiate between the units that were frequently the object of the “Who is the most badass?” inquiry. Pros on the forum reviewed this summary favorably, and has since been treated as a reference thread.

Special Forces – force multipliers; unconventional warfare experts as MikeLogics pointed out. Their job is to win over the local populace to the government’s side and to organize/lead them against the enemies of the state. This is the reason why CAFGU organization was originally their domain (and remains so to a certain extent). Their arsenal is not limited to their weapons, but include their smiles and personality. (There’s a reason why a lot of times they’re the ones manning the exhibits during Philippine Army day)

Based on the “A” in their acronym [SFRA], they have a thing about jumping out of aircraft that are working just fine.

Scout Rangers – tip of the spear. COIN is about offering the choice between the carrot and the stick. The rangers are the stick. Whereas SF and SOT teams mingle with the population, Rangers avoid contact to keep the enemy guessing about their whereabouts. (This, according to Victor Corpuz, is the reason why Ranger-only operations don’t work — you need an SF/SOT component)

Force Recon – vanguard of the MBLTs. The PMC reportedly doesn’t really consider Force Recon an elite unit. Since PMC doctrine emphasizes combined arms tactics, all units are part of a whole and just have different jobs. Force Recon’s job is harder than of other units since they’re the ones who are supposed to find / make first contact with the enemy, and consequently fire the first shots.

NAVSOG/SWAG – just add water. When you need an offensive punch from the sea, short of a full-scale amphib operation, these guys are it. (No idea if there are any doctrinal limits to how far in-land they can be used). Armed seaborne operations, such as underwater demolition and hostile-boat boarding are part of the menu.

Modernization projects don’t die. They just get re-labelled

Friday , 5, August 2016 Philippine Navy Leave a commentIn the twilight of the Arroyo administration, the AFP was poised to embark upon its most ambitious, most expensive project in AFP history. What would become the largest naval vessel ever to join the fleet the Multi-Role Vessel (MRV) project.

As per PN sources, it was supposed to have consisted of one South Korean-built LPD based on the Makasaar class coupled with a partnership agreement with a yet unselected local partner to build 5 more in the Philippines. After years of negotiation, the DND and the Republic of South Korea had agreed upon project pricing as well as a cap on project escalation costs. The initial vessel would have included the following components

|

By September 2010, P2B had already been allocated for the project — taking advantage of the then brand new budgetary instrument the DND’s arsenal: the Multi-Year Obligating Authority.

|

To the horror of the individuals intimately involved in MRV negotiations, when the Aquino administration took over power from Arroyo, all existing projects were suspended. Budgets already allocated — to include the P2B already set aside for the MRV — were earmarked for re-allocation.

The MRV project, as already negotiated, was dead.

However . . . a mere five years after that calamitous turn of events that saw career PN officers resigning their commissions having lost sight of the way ahead for the Philippine modernization program, the BRP Tarlac entered service.

|

Gone was the original in-country manufacturing deal. In its place was a boost for the Indonesian shipbuilding industry. The AAV component had been spun off into a separate project that is also slated to be awarded to South Korea. The mobile hospital component was no more.

The specific of the MRV project had morphed into the Strategic Sealift Vessel. The Philippine Navy still got its ship.

Fast-forward to 2016. Another President . . . another project.

Reports emanating from the grapevine strongly suggest that the P18B Frigate Acquisition Project is headed for a deal-cancelling delay. While Hanjin Heavy Industries’ bid cleared post qualification hurdles the continued viability of its tender in the face of deferral of actual notice of award is causing the same concerns and general consternation as the original delay of the MRV.

This really should not come as a complete surprise. With a price tag of “P18,000,000,000.00”, it is simply too large of deal to slide through to the contract-signing-state without scrutiny or any form of due diligence on the part of leaders who would then be answerable to taxpayers for the selection.

Will the FAP go the way of the MRV project? There is cause to believe that it would.

That leaves open a number of interesting questions:

Does that put an end to the Philippine Navy’s efforts to acquire Frigates?

Absolutely NOT.

Sail Plan 2020, and the plans that came before it, are products of careful study of the country’s maritime security requirements. While many aspects of the minutiae of requirements definition may post technical challenges, the broadsrtokes for the necessary capabilities are well established. If not completed within the Duterte administration . . . it will be pursued in the next.

As demonstrated by the SSV project . . . the PN will put in the work to get the ships that it needs.

If the deal is indeed cancelled, does this mean that we are back at the start of the bidding process?

What Duterte ultimately decides will be known when he makes it. Predictions about what that decision will ultimately be is a function of the analyst’s faith in — or lack thereof — in the President’s capacity for reason. Setting crystal-ball-gazing exercises aside, we can at least look at the procurement framework within which the President is operating to see what he can do if he so chooses.

Short answer is NO

When the Aquino administration select the FA-50PH as LIFT, it represented the only time that it exercised the following provision in the Implementing Rules and Regulations for the government procurement law:

Negotiated procurement

Negotiated Procurement is a method of procurement of goods, infrastructure projects and consulting services, whereby the procuring entity directly negotiates a contract with a technically, legally and financially capable supplier, contractor or consultant only in the following cases:

. . .

g. Upon prior approval by the President of the Philippines, and when the procurement for use by the AFP involves major defense equipment and/or defense-related consultancy services, when the expertise or capability required is not available locally, and the Secretary of National Defense has determined that the interests of the country shall be protected by negotiating directly with an agency or instrumentality of another country with which the Philippines has entered into a defense cooperation agreement or otherwise maintains diplomatic relations: Provided, however, That the performance by the supplier of its obligations under the procurement contract shall be covered by a foreign government guarantee of the source country covering one hundred percent (100%) of the contract price;

Promulgation of the Defense System of Management (DSOM), comprehensive requirements definition and equipment selection process, within the AFP should have given the Aquino administration the doctrinal and budgetary definition for outright selection of equipment . . . WITHOUT the need for time consuming bids.

Sadly, for reasons that hopefully will come to light in time, after the FA-50 acquisition the Aquino administration refused to leverage this capability for subsequent modernization projects. As a consequence . . . the Frigate Acquisition Project is where it is now. Caught between two administration with an uncertain future.

Will the Duterte administration be gun-shy about using this authority to do away with public biddings and simply pick up where the Frigate Acquisition Project left off, and select South Korean frigates outright?

You be the judge

Contractors with lowest bid not the best for Duterte

Published August 2, 2016 9:53pm

By TRSIHA MACAS, GMA News

President Rodrigo Duterte said on Tuesday that he would not follow the government’s “lowest bid” rule in awarding contracts for government projects as it led to corruption and usually left the government with sub-standard equipment.. . .

The president explained that he did not want to purchase equipment that would not be durable.

“Pahabulan ng presyo, pababaan mo ang presyo mo. Iyong iba, 100, ipabili nito ng 20, eh ‘di ipabili mo nalang sa akin iyong made in–alam mo na. Huwag muna ngayon kasi may alitan tayo. Tapos sabihin ng mga sundalo, ‘Sir, nasira agad.’ Kagaya ng jeep ng police. Tignan mo iyong binili nila. Wala na. Sabi ko, ‘Huwag mo akong bigyan ng sh-t na iyan.’ Ako, ang pulis ko doon [Davao City], Isuzu, and it will last for about three to five years. Huwag lang ibunggo ng mga buang,” Duterte said.

“Iyong [medical] equipment ninyo, state of the art. Bahala na mahal. Ayaw ko iyong gagamitin, nasisira,” he emphasized.

Duterte said that to get the best, he would ask experts to guide him on which had the best value.

< Edited >

– See more at: http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/576085/news/nation/contractors-with-lowest-bid-not-the-best-for-duterte#sthash.KNNgElAr.dpuf

This article is also available on the Timawa.net forum here.

What is the FA-50PH really for?

Saturday , 16, July 2016 FA-50, Philippine Air Force Leave a commentThe Korean Aerospace Industries FA-50PH is the single most sophisticated aircraft in the Philippine Air Force inventory. The arrival of the first two aircraft on November 28, 2015 heralded the formal start of the service’s efforts to rebuild it’s air defense operations capability. These two “Fighting Eagles”, as South Korea calls them, were the first of what will ultimately be 12 aircraft. According to multiple PAF sources, two more aircraft are due in the final quarter of 2016, while the remainder will be delivered in 2017 at a rate of one a month.

The aircraft in question appears below. Photographs c/o Lester Tongco, reposted with permission.

|

|

The FA-50 represents many firsts for the PAF, to include the following:

- First brand-new fixed-wing combat aircraft acquired since the F-5A Freedom Fighters that were acquired in the early 60s.

- First aircraft with fly-by-wire technology

- First combat aircraft capable of integrating with network-centric warfare environments

- First supersonic aircraft since the retirement of the last F-5A in 2005.

On February 19, 2016, these two aircraft conducted an air interception exercise involving a Philippine Air Lines Airbus carrying President Aquino who was returning from a US-ASEAN summit in the United States. This was reportedly the first intercept exercise of its type attempted by the Philippine Air Force since 1998 using its now retired F-5As. This exercise not only benefited the pilots of the aircraft, but also practiced coordination between air traffic controllers of the Civil Aviation Administration of the Philippines (CAAP) and the PAF’s Air Defense Wing. CAAP and PAF controllers were responsible for tracking the President’s aircraft and guiding the FA-50s to a point where they could use their own radars to find the airliner.

During the PAF’s heyday, in the US-bases funded 60s, such intercepts were part of normal operations for enforcing the Philippine Air Defense Identification Zone (PADIZ). During this period PAF fighters would intercept all manner of aircraft, from Soviet bombers transiting the South China Sea enroute to Cam Ranh Bay in Vietnam, to Air Force One on a visit to the Philippines as shown below.

|

| Photograph c/o Francis Neri Albums |

These aircraft, however, appear to have a questionable future under the administration of President Rudrigo Duterte, who raised a firestorm in defense social media circles when he called the FA-50 “useless” at an economic consultation forum in Davao City on the 21st of June

The President had the following to say about the crown jewel of the PAF’s jet-aircraft fleet. Relevant excerpt begins at Time index 36:07:

| Video | Excerpt: | |

| DUTERTE: “You only have . . . what . . . two F-50s? Bakit mo binili yan?

Kayong mga taga Air Force, do not misconstrue my . . . I am a Filipino, I’m a citizen of this country and I have every right to say what I want to say. Sayang ang pera doon. You cannot use it for anti-insurgency which is really the problem of the moment. You can only use it for ceremonial fly-bys. What do I care about <fade out>. Kung binili mo ng choppers na may night vision, you when the kidnapping . . . you could have a catch up those guys There’s only one purpose for buying it. To match the airpower . . . at least 1-on-1 sa China. Pero, beyond that Scarborough Shoal, anak ng hueteng there are 300 Migs there. They can reach Manila in 6 minutes” |

Duterte’s objections to the aircraft are predicated upon three assumptions:

- The FA-50s were acquired to counter Chinese air power in the West Philippine Sea

- FA-50s cannot be used for the anti-insurgency campaign

- The AFP prioritized the FA-50s in lieu of helicopters with night-fighting capability

This article seeks to fact-check these assumptions.

Assumption 1: The FA-50s were acquired to counter Chinese air power

The short response to this would be: “No it is not”.

A detailed answer will require an understanding of what the FA-50 can and cannot do, and a high-level review of the AFP modernization program as a whole. To draw attention to the misconceptions surrounding this aircraft, both among its critics and even some of its well-meaning supporters, this article will begin with what the aircraft can’t do.

Had the Philippine Air Force sought an effective counter to Chinese fighters, the FA-50 would have been a poor choice. In South Korean Air Force service, the Fighting Eagle is a replacement for aging F-5E and F-4 fighters. Both are second-string combat aircraft relegated to supporting roles for Korea’s principal fighters, namely the F-15K air superiority fighter and the relatively smaller — but still formidable — F-16K multi-role fighter.

The FA-50s range is limited. Airforce-technology.com cites a range of 1,851 km for the pure trainer version of this aircraft: the T-50 . While the Fighting Eagle’s actual range is classified, the fact that it’s external dimensions are virtually identical to the T-50, it stands to reason that it’s range would be no better, and could only be worse given the range-sapping external weapons pylons and the weight of additional equipment of the FA-50. In contrast, the smaller of the multi-role fighters cited above — the F-16 — has range of 3,221 km.