Philippine Defense Today (Adroth.ph)

In Defense of the Republic of the PhilippinesA role for seaplanes in the Armed Forces of the Philippines

Saturday , 8, August 2015 AFP modernization, Philippine Air Force, Philippine Navy Leave a commentSeaplanes and flying boats are aircraft with the unique ability to travel to any marine destination, at fixed-wing-aircraft speed, and then land and take-off from water. It is a category of aircraft that is — theoretically — well suited to an archipelagic country like the Philippines.

The Philippine Navy’s 15-year development plan calls for the acquisition of eight (8) Amphibious Maritime Patrol Aircraft. More recently, the Philippine Air Forces issued a P2.6B invitation to bid for three Search and Rescue seaplanes in November 2013. Both acquisitions, however, are currently on-hold. This suggests that while the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) recognizes the value of this category of aircraft, they are not particularly high in the priority list. Which is unfortunate given the unique missions that only they can perform.

In this article, let us explore this category of aircraft, the different sub-categories within, their operational challenges, and the roles they play.

Seaplanes, flying boats, atbp.

The term “seaplane” is often used to describe all planes that take off and land on water. But this really only correctly describes one type of machine.

Seaplanes have floats beneath their aircraft upon which they land on water. The floats serve as their landing gear, and are typically permanently suspended beneath the plane. This aerodynamic penalty is the price paid for marine operation.

Flying boats, on the other-hand, have specially designed fuselages designed to operate in water. This makes for an aerodynamically clean fuselage. Some designs have additional floats on the wings to keep the plane upright in the water, while others have specially designed extensions that serve this purpose.

“Amphibians” are a sub-category of flying boat that land on water exclusively, and only use their landing gear to taxi from water on to land. On paper, this is the type of aircraft that the Philippine Navy is eyeing. Lack of clarity about the Authorized Budget for Contract that will be allocated to the project makes it difficult to predict the outcome of the project.

The Armed Forces of the Philippines has operated both seaplanes and flying boats over the years, but have since retired them.

|

|

|

| Cessna Grand Caravan seaplane. Photo c/0 Air Juan Website |

PAF HU-16 Albatross Flying boat |

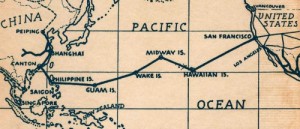

In the early 20th century, when limitations on aircraft endurance necessitated more refueling stops than there were aerodromes, flying boats like the PanAm Clippers were the only way to fly, for example, from San Francisco to Manila. This could be done by way of water landings at Honolulu, Midway, Wake, and Guam. The path they took appears in the map below, taken from the Website clipperflyingboats.com.

|

| Photo c/o clipperflyingboats.com |

Advances in aviation design have since made it possible to fly previously unimaginable distances without refueling. Today Philippine Airlines regularly flies the San Francisco to Manila route via direct 13-hour flights.

Since World War II, seaplanes and flying boats have been relegated to specialized roles, and only by a drastically reduced number of countries. Early champions of the aircraft type, the United States and the United Kingdom, have all retired their floatplanes without replacements. Japan, Russia, and Canada are the only remaining players in the military / government flying boat market. Other manufacturers, like Cessna and Dornier, are mainly aimed at the civilian market which focus on light aircraft for niche applications.

The reasons for this decline are multi-faceted and are beyond the scope of this article. But among them are the challenges inherent to this aircraft type.

Operating seaplanes

The book Corsairville: The lost domain of the flying boat by Graham Coster is a travel book that sought the story behind a British flying boat that crashed in the Belgian Congo. As part of that exploration, the author chronicled the changing attitudes towards seaplanes and flying boats. It contained numerous interesting insights into the challenges of operating seaplanes, which could be summarized as follows:

- Salt vs aluminum

- Water landings

- Foreign Object Damage concerns

Salt vs aluminum

Salt water is corrosive. This is obvious to anyone who’s been on a ship or frequents the coasts. While marine aluminum is more corrosion resistant than steel (corrosion rate of 1mm/year versus 120mm, see here), corrosion still occurs. This necessitates measures to combat this phenomena.

The following quotes from the book directly reference this issue. Note that “Seaplane” and “Pan-Am Air Bridge” were seaplane operators that the author used for his research into seaplane operations.

A floatplane did little more that dip its toes in on each landing, but at the end of everyday, Seaplane‘s Cessna had the hose turned on it for an hour and a half.

. . .

Two out of Pan-Am Air Bridge’s (aka Chalk’s Ocean Airways) 5 Mallards needed work . . . That insinuating, continuously destructive, salt again: everyday they had to run fresh water through the airframes, wash down the hull, apply all kinds of preservatives, coat rivet lines and joins with grease. ‘For every hour we fly’ . . . your going to take 3 to 4 hours of maintenance.

Philippine aircraft operators are no strangers to salt. With a significant portion or all airports and airfields being close to the sea, and salty sea spray, measures to control the build-up of this corrosive substance, ideally, ought to be common place knowledge. However, an aircraft that deliberately makes contact with salt water will require additional attention to ensure longevity.

Water landings

Whereas salt water’s effects on the seaplane’s airframe presented what amounts to an inconvenience to its maintainers and the organization that operates them, the floatplane’s operating environment presents challenges for its pilot.

The book presented insights from a former Sunderland pilot. The Sunderland is a British flying boat shown blow. This particular photo shows an Australian example of the aircraft.

|

Here are the pilot’s thoughts about the idiosyncracies of floatplane flight:

For a take-off, once you were out on the water, everything was variable. ‘It won’t just sit on the runway — it’ll roll — so the wings won’t stay level: you have to use the ailerons. Then, because of the torque of the engines, it’ll swing: you have to use the rudder to keep it straight’. Because the swing was habitually to port, you opened up the port engines first, and built up speed to 50, 60 knots until the flying boat’s 5-foot draught was out of the water and the craft was planing on its step . . .

The variability of the landing surface also requires an additional skill for pilots: “reading the water”. The following excerpt from the book illustrates this skill, c/o an interview with an Alaskan seaplane pilot.

See those black spots in the water?’ They were like scuffmarks, bruise-shadows in the indigo bay. ‘That’s where the wind is denting the water — coming down over this mountain and kind of bouncing off it’. Cat’s paws was the aviator’s nickname for them, because they also looked like a scatter of prints: the sight of them warned you that as you descended below that mountain the gusts could knock you about. Over east in the next bay . . . the water was fish-scaled silver . . . like silver-thread cloth, but said Fred, that fish-scaling was the wind whipping up the water. Try to land near that and both descent and touchdown would be a lot rougher. ‘We learn to read the water.’

The Federal Aviation Authority’s seaplane manual highlights the conditions that pilots have to “read”:

While a land plane pilot can rely on windsocks and indicators adjacent to the runway, a seaplane pilot needs to be able to read wind direction and speed from the water itself. On the other hand, the landplane pilot may be restricted to operating in a certain direction because of the orientation of the runway, while the seaplane pilot can usually choose a takeoff or landing direction directly into the wind.

Even relatively small waves and swell can complicate seaplane operations. Takeoffs on rough water can subject the floats to hard pounding as they strike consecutive wave crests. Operating on the surface in rough conditions exposes the seaplane to forces that can potentially cause damage or, in some cases, overturn the seaplane. When a swell is not aligned with the wind, the pilot must weigh the dangers posed by the swell against limited crosswind capability, as well as pilot experience.

While landing gears provide some level of forgiveness during hard landings, such landings for a flying boat have serious consequences, as shown in this excerpt from Corsairville:

Ken Emmott had once had to swim for it . . in Southampton Water when his BOAC captain had landed too fast, bounced their Sunderland off the water and cut away a large section of the nose before they sank to the bottom.

The Federal Aviation Authoriy’s seaplane manual affirms the plane’s sensitivity to hard landings

Because floats are mounted rigidly to the structure of the fuselage, they provide no shock absorbing function, unlike the landing gear of landplanes. While water may seem soft and yielding, damaging forces and shocks can be transmitted directly through the floats and struts to the basic structure of the airplane.

Foreign Object Damage concerns

The unique handling characteristics of seaplanes and flying boats require specialized training and flight experience. But there is one issue that no amount of flight training can completely address: debris.

The FAA seaplane manual offers the following guideline for seaplane landings:

It is usually a good practice to circle the area of intended landing and examine it thoroughly for obstructions such as pilings or floating debris, and to note the direction of movement of any boats that may be in or moving toward the intended landing site. Even if the boats themselves will remain clear of the landing area, look for wakes that could create hazardous swells if they move into the touchdown zone.

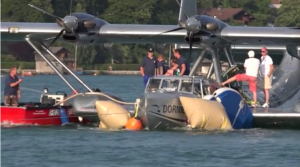

Ocular surveys from the air, however, can only go so far. As Iren Dornier and his crew demonstrated spectacularly at an Austrian airshow in Salzkammergut in July 2015.

Dornier, the pilot, is the grandson of the German Aviation Pioneer Dr. Claude Dornier and has significant investments in the Philippines to include South East Asian Airlines (SEAir) and a flying boat factory at the former Clark AFB in Pampanga, where his company manufactures the S-Ray 007 amphibian. He and his crew had been flying their refurbished World War 2-era DO 24ATT flying boat as part of a round-the-world tour to raise funds for the UNICEF, and were thus experienced flying boat operators. His floatplane credentials and lineage are impressive. That, however, did not make him or his crew them immune to floating debris.

The following photographs show what happens if a flying boat makes contact with unseen floating debris (believed to be a tree trunk) during landing. The object tore a fist-sized hole in the side of the DO 24ATT flying boat, which then took on water. The plane had to be towed to shore. None of the crew were injured.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Video of the event available below

Given the amount of debris in Philippine water ways, from flood water run-off, garbage thrown off ships, and cast-offs of various marine economic activities, the probability of similar contact is not insignificant

Bodies of water are constantly changing. Even if a seaplane were to take off and land from the same location. The condition of that landing point will never be same as it was when the plane took off from it. What was safe when the pilot left it, might not be so upon return. It is that variability that increases the uncertainty.

Seaplanes alternatives

Arguably, one contributory factor to the decline of the seaplanes and and flying boats was the rise of the helicopter. It replaced the floatplane as the preferred platform for non-aircraft-carrier-based aerial missions. Seaplanes used to perform reconnaissance, liaison, and search and rescue missions from ships large enough to accommodate them.

In World War II, some vessels could launch their planes using catapaults. However to recover them, the ship had to stop to bring the plane back onboard — a risky and time consuming maneuver. If the sea state around the recovering ship was unfavorable, landing alongside the recovery ship would be impossible.

|

|

|

| Catapault launch photo c/o Pacificaviationmuseum.org | Seaplane recovery photo c/o Pacificaviationmuseum.org |

Helicopters on the other hand could land on ships while underway, and in a broad range of sea states. They could also rescue individuals in the water, without needing to risk the aircraft in a water landing, by hovering above them and lowering a rescue winch.

Long range maritime patrol missions have also been traditional fixtures the flying boat’s offerings. The same qualities that made floatplanes the principal means of air travel across the Pacific, also made them the ideal maritime patrol aircraft for their time. Their ability to take off from water meant that they could be based closer to the intended patrol area without needing runways, and could be refueled and re-provisioned by ship.

However advances in aviation technology have given conventional land-based aircraft the range and reliability to perform such missions, all from the safety of a non-variable runway . Furthermore, land-based aircraft do not require the aerodynamic compromises imposed by water landing requirements (e.g., floats and associated struts, etc.) thus improving performance.

Air forces simply no longer needed flying boats for the bulk of their traditional missions. But . . . not all.

Flying boats, and to a large extent seaplanes, retain the advantage of speed over helicopters. Whereas a relatively slow World War II flying boat like a PBY Catalina only flies at 189 mph, the Philippine Navy’s newest multipurpose helicopter, the AgustaWestland AW109 only had a maximum cruising speed of 177 mph. That speed advantage is a key differentiator.

|

|

|

| PAF PBY Catalina photo c/o Francis Neri Albums | AW109 photo c/o Philippine Navy |

Justifying the risk

Water take off and landings compound the dangers already inherent in flying. If a helicopter or a conventional plane can do the mission better and safer, then the suitability of a floatplane for that task is debatable. However, there are specific missions that only seaplanes and flying boats are able to perform. These are unique requirements that justify their expense, both in pilot training and additional maintenance for the aircraft, as well as the risk inherent to operating from water.

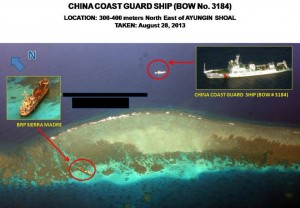

No place in the Republic of the Philippines better illustrates the potential for floatplane use better than the garrisons in the West Philippine Sea. Among them, the BRP Sierra Madre, which serves as the republic’s outpost on Ayungin reef. Because of its proximity to Panganiban Reef, known internationally as Mischief Reef, this ship is on the frontline of the EEZ conflict between the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China.

|

|

|

AFP Western Command resupplies this station by sea and by air. These missions are performed on a regular schedule, and the station itself is stocked with supplies to accommodate unexpected delays that, in the past, have doubled the tours of duty of the Marines guarding the ship.

Troop rotations are performed by boat. For Operational Security (OPSEC) reasons, exactly how resupply boats reach the station despite the Chinese blockade will not be discussed here.

Consumables and care packages, on the other hand, can be air dropped to the ship. Items are placed in sacks which are then enclosed in plastic along with bouyancy aids such as styrofoam. These are then dropped in the water beside the the outpost and the resident Philippine Marines simply bring them onboard. See inset on the photo below on the right.

|

|

||

| Logistic air drop. Photo c/o Philippine Navy | Philippine Navy islander dropping cargo. Photo c/o Philippine Air Force |

To summarize the state of logistic affairs on Ayungin, existing techniques allow for either slow transport of large quantities of personnel and provisions, or rapid delivery of modest quantities of supplies. Neither method, however, can be used for rapid extraction of men or materiel. Which also means that neither method would be suitable for Medical Evacuation (MEDEVAC) missions. If AFP personnel on these outposts ever fall seriously ill or are injured, they will be in for a long wait before they can be given proper medical care.

Heli-deck equipped vessels, such as the Del Pilar class frigates, Frank Besson LSVs, even Philippine Coast Guard Tenix boats, could presumably dispatch helicopters to recover a stricken individual from the outpost. Rotary-wing aircraft could fly over any Chinese blockading ships to reach their destinations. But the ships would still have to travel to within helicopter-flying distance to be effective. Furthermore, the medical facilities on these ships are limited — none are normally equipped for tertiary care. Once the patient is onboard, they would still have to sail at best possible speed to an alternative medical facility.

Seaplanes and flying boats would be the logical choice for the MEDEVAC role, as they are the only aircraft that can embark passengers from WPS outposts, and travel with sufficient speed back to air bases in Palawan, Metro Manila or at the very least to the medical health center on Pag-asa island.

These aircraft could also be used to satisfy the MEDEVAC needs of Philippine Navy and Philippine Coast Guard ships on patrol or remote island communities in other parts of the Philippines. While acquired primarily for a military purpose, it has windfall benefits for the general population.

This is an operational challenge that needs a solution. The defenders of the West Philippine Sea deserve nothing less than the country’s best effort in ensuring access to medical treatment within the all-important Golden Hour, during which medical intervention will yield the most benefit. Philippine Navy or Philippine Air Force floatplanes, whichever service gets them first, offer the best means for satisfying this need.

|

About this article

The base research for this article was completed in 2006, as part of back-end work for the following thread on the Timawa.net forum: Operating Seaplanes.

Promoting your blog at the expense of your sources and operational security

Saturday , 4, July 2015 Uncategorized Leave a commentThe modernization community is very very small. What you choose to reveal about a project can very well betray your source. Details that, in reality, you should not even know in the first place . . . if it were not for the trust that that person placed in your discretion. The deeper you get into modernization research, the more you encounter information that you CAN’T reveal. That’s why RESPONSIBLE people who are in-the-know, tend to just shut up about the various projects both for operational security, as well as the personal security of the people that confide in them. In your effort to promote your blog as the go-to source for defense information, you could have very well just ended a career or two, and tainted a bunch of others. EGAD

Strategic Sealift Vessels (SSV) on the way

Sunday , 7, June 2015 Philippine Navy, SSV Leave a commentThe Philippine Navy’s two Strategic Sealift Vessels are now both under construction, with the steel cutting ceremony for the second SSV taking place on the 5th of June. The first vessel had its equivalent ceremony in January and is expected to be launched in November 2015 with full completion by May the following year.

The Strategic Sealift Vessel project is the Aquino administration’s implementation of two older Arroyo administration projects:

Strategic Sealift Vessel – this was reportedly crafted by the Center for Naval Leadership and Excellence (CNLE) and originally envisioned to acquire a 2nd-hand civilian Roll-On Roll-Off (RORO) vessel from Japan. Delays in the execution of the project resulted in an aborted attempt as the Japanese vendor choose to sell the prospective vessel to another buyer.

Multi-Role Vessel (MRV) – this project sought to acquire a brand-new Makasaar class Landing Ship Dock directly from South Korea complete with an amphibious assault package and a sophisticated mobile hospital. The following image of a Philippine Navy poster displayed on Navy Day shows what this project sought to acquire as a single project.

|

| The original project that was broken up onto different components |

The current administration opted to break up the MRV project into multiple components, award the contract to South Korea’s partner in Indonesia — which incidentally had the license rights to the Makasaar class LPD — and then rename the project to the current SSV title. The latter decision initially created confusion among long-time defense enthusiasts who had been aware of both projects, but were not privy to project decisions.

|

|

|

| SSV-1 steel cutting ceremony | SSV-2 steel cutting ceremony |

As shared by an Indonesian Timawan with ties to PT PAL, the shipbuilder responsible for the construction of the two vessels, construction of the keel for SSV-1 is well underway. Credit for the following photographs of the SSV-1 keel, and translation of the Indonesian news article, go to the member who goes by the username “Gombaljaya” (or Alberth Minas on the Timawa FB extension)

|

|

As the ships themselves are progressing, so too are other components of the original Multi-Role Vessel package. The contract to supply Amphibious Assault Vehicles (AAV), which comprise part of the SSVs offensive punch, are slated to be awarded to Samsung Techwin, which will provide the South Korean version of the American AAV7 amtrack.

Discussions about the two SSVs are available on the Timawa.net forum at the following locations:

New Facebook page for Philippine Defense Today

Tuesday , 6, January 2015 About this blog Leave a commentAs part of Facebook usage adjustments for 2015, this blog’s companion FB page has moved to the following URL:

https://www.facebook.com/adrothph

Although the previous FB page remains, it will no longer be updated.

The Timawa Facebook extension experiment is at an end

Wednesday , 24, December 2014 About this blog Leave a commentNote: This is also posted on the Timawa.net forum here.

In an effort to broaden the community’s reach I experimented with the creation of Facebook extension for select Timawa topics for the following functions:

1. Focus laser-like attention on specific areas of concern, and to both promote discussion on them as well as to gather useful useful information for the mother forum.

2. Serve as a “newbie sandbox” for potential forum members, so that individuals could get a taste of Timawa-style posting discipline before actually joining in. This was tied to efforts to stem the tide of stupidity that had been inundating the forum

This experiment stared in 2011 coinciding with the creation of the Adroth.ph blog that sought to summarize, and highlight the best, discussions on the forum.

The Facebook account policy explicitly requires that individuals use their real names in their accounts, with no obfuscation

Facebook is a community where people use their authentic identities. We require people to provide the name they use in real life; that way, you always know who you’re connecting with. This helps keep our community safe.

Please refrain from adding any of these to your name: Symbols, numbers, unusual capitalization, repeating characters or punctuation.

Characters from multiple languages.

Titles of any kind (ex: professional, religious).

Words, phrases or nicknames in place of a middle name.

Offensive or suggestive words of any kind.

I’ve carried the name “Adroth” for the better part of 14 years and there are in fact friends that address me as such even in real-life, especially if we started our friendship on the forum. Though not strictly following the letter of the FB guidelines, it certainly satisfied it in spirit and intent

Respect for anonymity is the foundation of the Timawa community. We leave it up to individual members to identify themselves to fellow members at the time of their own choosing. Some of us do, especially to facilitate the few rare eyeball events that are organized for select projects. Others are content to remain faceless. Anonymity – even to each other — has never been a hinderance to our ability to organize real-life projects with real-life impact. The Timawa Donation Group has been operating in this mode and has conducted numerous humanitarian and pro-defense projects since 2006. In keeping with a policy that has served the forum well since its inception in 2000 – I saw no reason to abandon that mode of operation.

Compartmentalization. I don’t want to mix pictures and post filled with either slap-on-the-forehead ignorance or vile vitriol with photos of my family. I keep politics out of my personal FB page for that reason

Efficacy is our goal, not fame. Facebook apparently doesn’t see it that way – at least as of today — and has chosen to enforce its rules.

The following are the largest of the groups. Unfortunately these won’t grow any further and will be unmoderated.

|

2014: What’s happening with the AFP modernization program

Sunday , 21, December 2014 AFP modernization 1 CommentNote: This article is also available on the Timawa.net forum on the long standing What’s happening with the AFP modernization thread that’s been documenting the progress of the up-arming effort since 2003.

—–

The year 2014 continues the dramatic increase in defense acquisition efforts that started in 2010. Many of those efforts, however, remain unrealized as of year-end. While the year was long on award notices, it was noticeably short on deliveries. For this reason, the acquisition list at the end of this article will have many notable omissions since it ONLY shows deliveries that have actually been completed. The following high-profile projects are noticeably absent from the list:

Philippine Air Force

Surface Attack Aircraft / Lead-In Fighter Trainer (SAA/LIFT) – one of the highlights of the year was the signing of the long awaited purchase contract for the South Korean FA-50 Fighting Eagle Surface Attack Aircraft / Lead-In Fighter Trainer. After an arduous 5-year process — from concept to signing — the Philippine Air Force is finally slated to return to supersonic flight after almost a decade. These will also be the first brand new high-performance aircraft that the PAF will acquire since the factory-fresh F-5A Freedom Fighters in the 60s. Subsequent fighter acquisitions had focused on excess defense articles such as thethe F-8 Crusaders which were recovered from AMARC and 2nd-hand F-5As from South Korea. Although the project won’t actually yield aircraft till 2015 (hence their exclusion from the main table below), training of the initial batch of instructor pilots in South Korea is proceeding. Payment terms for the SAA/LIFT program were finalized on February 21st with first deliveries set to begin in late 2015. Details here.

SSA/LIFT munitions – the ordnance that SAA-LIFT aircraft will carry are being acquired via a separate acquisition project. These include Air-to-Air Missiles (312 Pieces), Air-to-Surface Missiles (125 Pieces), 20mm Ammo (93,600 Pieces), and Chaffs/IR Flares. Details here.

Attack Helicopter Acquisition Project – while the decision to award the contract to supply eight Agustawestland AW109 helicopters had been made in late 2013, the first deliveries aren’t scheduled till early 2015. Training of the flight and maintenance crews are underway in Italy.

Combat Utility Helicopter acquisition project – not to be confused with the CUH project that acquired the W-3 Sokol in 2009, this project sought acquire eight additional helicopters for combat and VIP duties. This project went to Bell Helicopter which will deliver Bell 412EP aircraft by 2015. Three of these helicopters will be delivered in VIP transport configuration. See here.

Medium-Lift Aircraft acquisition project – notice of award issued to Airbus for the delivery of three C-295 aircraft on February 2014. One aircraft is scheduled for delivery in 2015, with the remaining two for delivery in 2016. Details here.

Light-Lift Aircraft acquisition project – this project reportedly went to PT Digantara of Indonesia which will be supplying two CN212 aircraft. See here.

Philippine Navy

Strategic Support Vessel (SSV) – notice of award issued to PT Pal of Indonesia for the construction of two brand-new SSVs based on the Makassar class. Details here.

Amphibious Assault Vehicle (AAV) – Samsung Techwin was declared the lowest single calculated bidder for the P2.5B AAV project. Details here.

PF-16 weapons upgrade – the often reported installation of Mk.38 25mm RCWS remains pending. These were initially slated for installation prior to the ship’s departure from South Carolina but had been delayed. Timawa discussion here.

Marine Forces Imagery and Targeting Support Systems (MITSS) – this P684.32M project sought to acquire 6 sets of Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, 9 sets of Target Acquisition Devices, and 12 kits of Tactical Sensor Integration Subsystems. Details here.

40mm automatic grenade launcher – the DND issued a Notice To Proceed (NTP) in favor of Advanced Material Engineer / ST Kinetics, represented locally be Floro International Corp, to supply and deliver eight (8) units of 40mm automatic grenade launchers for the contract price of P19,750,672.00 on March 4, 2014. Details here.

Philippine Army

Armored Personnel Carrier acquisitions – the Philippine Army acquired 142 M113A2 armored vehicles, in various configurations, from the US as Excess Defense Articles (EDA) (Timawa discussion here) and 28 ex-Belgian Army M113s with Remote Controlled Weapon Systems (RCWS) from Israel (Timawa discussion here). Neither project has been delivered.

Rocket Launcher Light Acquisition Project – Airtronic USA, Inc. was selected to supply 400 US-made RPG7 rocket launchers, and associated 40mm rockets, as part of a Foreign Military Sale (FMS) deal. Timawa discussion here.

In addition to the projects for which notices of award (NOA) have already been issued, there are a number of other projects that remain in various stages of completion short of a NOA:

Frigate Acquisition Program – this P18B project seeks to acquire two brand new multi-role frigates in a complicated two-stage bidding process. To date, the following shipbuilders have signified interest in the project: Navantia Sepi (RTR Ventures), STX Offshore & Shipbuilding, Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering Co Ltd, Hyundai Heavy Industries Inc., Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers Ltd of India, STX France SA. Details here.

Anti-Submarine Helicopter Acquisition – as of writing, Agustawestland was the only company that qualified to take part in the bidding in November. See here

Long Range Patrol Aircraft acquisition project – the DND declared a bidding failure in August due to documentation deficiencies among bid participants. see here.

Close Air Support Aircraft acquisition project – bid submission for this project was moved to January 7, 2015 by virtue of Supplemental Bid Bulletin PAF-CASA 14-12-001. See here.

Air defense radar acquisition project – like the SAA/LIFT project, this P2.68B acquisition is part of the PAF’s systems approach to reviving the country’s ability to enforce the Philippine Air Defense Identification Zone (PADIZ). This project has been the subject of much speculation, with very little official discussion. The TPS-77 and Elta ELM 2288 are touted as contenders for this project, however media reports have touted the Israeli contender as being favored. See details here.

155mm Towed Howitzer project – the Philippine Star reported that Elbit Systems, an Israeli defense company, won the bid to supply 12 units of 155mm howitzers. To date, however, a notice of award has not been posted on the DND Website. See here.

Land-based Anti-Ship Missile project – this high-priority project was discussed in the press briefly but has since progressed quietly, away from the limelight. See here.

In addition to acquisitions via bidding, South Korea has committed to providing the Philippines with one surplus Pohang Class corvette, a landing craft, and several rubber boats. Two C-130T Hercules are also being acquired from the United States as EDA. These and the aforementioned Korean acquisitions have yet to be delivered and have therefore been omitted from the list below.

|

The acquisition list

The following list focuses on actual deliveries of equipment that were made in 2014.

|

Multi-Purpose Helicopter Acquisition Project |  |

The contract for the delivery of two additional AW109 helicopters was signed in February 2014, and the units were delivered to the PN in late December 2014, thus completing the order. Timawa.net discussion here. Photo c/o the Francis Neri albums shows the original units delivered in 2013. |

| Underway replenishment ship acquisition |  |

Three retired tankers from the Philippine National Oil Corporation, c/o PNOC Shipping and Transport Corp., were donated to the Philippine Navy, on March 26, 2014, to serve as replenishment ships. Timawa discussion here.

The former MT Lapu-Lapu is now PN Tanker 1, and MT Rizal is PN Tanker 2. Photo shows one of the tankers, PNOC Lapu-Lapu, while it was still in PNOC service in 2011. Shared on Flickr by fangedboy8 here |

|

| Refurbishment: Britten-Normal Islander |  |

Four BN Islanders were refurbished and returned to service in January 2014. Timawa discussion here. Photo c/o Philippine Navy Website. | |

|

Refurbished UH-1H acquisition project |  |

After numerous aborted efforts, the PAF finally awarded a contract to supply 21 UH-1H helicopters to Rice Aircraft Services. Four units arrived in June, in time for the PAF anniversary on July the 1st. Timawa discussion here |

|

Assault rifle acquisition project |  |

Remington Arms won the contract to sell the 50,629 pieces of M-4 assault rifles to the Philippines in 2013. The first deliveries for this contract arrived on July 5, with another delivery on July 31. Timawa discussion here. Incrementally, ground units will have their existing rifles replaced with these new units. The older rifles are slated for refurbishment and will be issued to reserve units, as per CSAFP Catapang. See here. Photo c/o Manila Bulletin |

| Boots, combat, lightweight |  |

The Philippine Army sought to replace its traditional leather boots with lightweight combat boots. Called the Hukbong Katihan Boots, or “Kubar” for short, that leveraged athletic shoe technology c/o a local company: Filboot. The boot was evaluated by the PA Research and Development Center in November 2013. However, after 5,000 pairs were delivered in early 2014, complaints arose over their quality. Philippine Army spokesman LTC Noel Detoyato hinted at a possible cancellation of the acquisition. Timawa discussion here | |

|

M-16A1 refurbishment program |  |

The GA Small Arms Repair and Upgrade Division(SARUD) delivered another batch of 980 refurbished 5.56mm M-16A1 rifles to the DND. SARUD and DND are in the midst of a program to refurbish 8,000 non-functional AFP rifles were were previously in LOGCOM storage. This program, however, has been halted pending acquisition of additional barrels as those remaining in inventory were found to be unacceptable. Timawa.net discussion here. |

| M1911 refurbishment program |  |

SARUD turned over seventy (70) units of refurbished M1911A1 0.45 cal pistols were turned over to the Philippine Navy. Timawa discussion here | |

| Multi-Station Machine |  |

Waterbury Farrel of Canada delivered a multi-station machine for primer insertion & crimping, depth gauging and head & mouth varnishing. Timawa discussion here |

SRDP opportunity to develop jammers for China’s GPS?

Wednesday , 12, November 2014 Self-Reliant Defense Posture Leave a commentMost modern smart munitions use a combination of GPS and Inertial Navigation Systems (INS) to achieve their phenomenal accuracy. Loss of one option, therefore, doesn’t completely negate the “smartness” of the weapon. Both, however, are needed to work as advertised.

Of the two options, the GPS component is most vulnerable to outside interference because it is susceptible to jamming, as the Russians have advertised in the past, and for which Saddam-era Iraq spent a fair amount.

From: http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/safeguarding-gps/

Indeed, it was the potential vulnerability of GPS to jamming that prompted Iraq to purchase a number of GPS jammers fromAviaconversiya Ltd., a Russian company that has been hawking GPS jammers at military hardware shows since 1999. The high-priced and high-powered GPS jammers offered by Aviaconversiya were said to be able to jam GPS signals for a radius of several miles. The Iraqi military used at least six of these high-powered GPS jammers, which cost $40,000 or more each, during the war. All six were quickly eliminated by U.S. forces over the course of two nights. Officials won¿t provide details, but considering the speed with which they tackled the problem, the Iraqi GPS jammers may initially have been somewhat effective.

|

Photo from China Defence Blog

China actually has its own GPS-equivalent known as Beidou, which was composed of nine satellites as of 2011, flying over China, the Korean peninsula, the WPS, and Australia.

Photo below from: http://www.astronautix.com/craft/beidou.htm

|

Isn’t it time for the AFP to acquire its own Beidou jammers?

Or better yet . . .

. . . develop its own as a medium-term SRDP initiative.

Concerned about North Korean use of the Chinese navigation system for its own smart munitions, South Korea is reportedly already looking into measures to jam the system. See the following paper written by researchers at Konkuk University, Seoul, South Korea.

At least some frequencies at which Beidou operates are known. The following text is from: http://gpsworld.com/signal-quality-of-galileo-beidou/

BeiDou M6. BeiDou satellites transmit navigation signals in three different frequency bands, all are located adjacent to or even inside currently employed GPS or Galileo frequency bands. The center frequencies are for the B1 band 1561.1 MHz, B3 band 1268.52 MHz, and B2 band 1207.14 MHz.

In 2012, China launched six satellites: two inclined geostationary space vehicles and four medium-Earth orbit ones, concluding in September (M5 and M6) and October 2012 (IGSO6). There have been further BeiDou launches in 2013, but these satellites’ signals are not analyzed here.

This would present an interesting opportunity to the proposed PH DARPA. This would just be the kind of competitive crowdsourcing effort that this organization could undertake, and leverage the following factors in its favor:

1. Compared to other projects (e.g., basics of air defense, ASW, etc.) this is NOT a critical, time-sensitive need. Therefore it is low-risk

2. There is a relative abundance of local engineering talent for such projects

Interested in exploring this opportunity further? Visit the following discussion at Timawa.net: http://www.timawa.net/forum/index.php?topic=38904.0

Timeline: Pag-asa Island sheltered port project (Updated October 2014)

Wednesday , 8, October 2014 #pagasaKIG Leave a commentUpdate to this article

This article has been updated to include Secretary Voltaire Gazmin’s statement about putting all national government funded improvements on Pag-asa Island in abbeyance. To date, no significant progress has been made towards construction of this port. This is stark contrast to China’s own efforts on Johnson and Gavin reefs. #pagasaKIG

| Photo of Chinese island building on Johnson reef c/o IHS Jane’s 360 |

|

About Pag-asa

The fishermen and municipal workers and families that live on Pag-asa Island comprise the most isolated civilian community in the Republic of the Philippines. The island, the largest of eight (8) Philippine occupied coral outcroppings in the Municipality of Kalayaan, is approximately 509 kilometers northwest of Puerto Princessa and 828 kilometers southwest of Metro Manila. Once a strictly a military installation, Pag-asa was opened to civilian settlement in 2002.

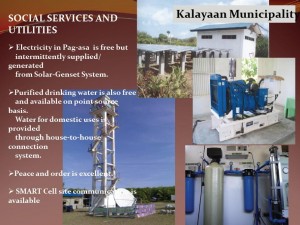

|

Since the creation of the settlement, the Municipal government of Kalayaan has established a range of facilities that provide vital public services that are expected of a functional community. Pag-asa has a power station consisting of a solar panel farm, charging a bank of 48 batteries, as well a conventional fossil-fueled generator to provide for the island’s electrical needs. The island’s reverse osmosis plant converts seawater into potable drinking water that residents collect from the plant. Water for domestic use is piped into individual homes.

|

Smart Telecommunications established a cell site, connected to its main network via VSAT (Very Small Aperture Terminal), on the island in 2005 making normal GSM-based cellphone communication with the island possible. The first call on the system took place on June 12 at 5:18 PM between the mayor of the municipality at the time and a Smart Telecom executive. The company completed a maintenance visit to the cell site in 2011, thus ensuring continued operation of the facility.

|

In 2012, the municipal government entered into a Memorandum of Agreement with the Department of Education to establish the Pag-asa Elementary School. There are currently 24 children that call Pag-asa, Kalayaan home. Fourteen are from fishing families, while the other 10 are children of municipal workers. Children of the latter go to school in Palawan. As of last year, 8 of the 14 enrolled in the Pag-asa Elementary School. Five were still too young to go to school and were candidates for the next school year. One child was un-enrolled. By mid-school year, the teaching staff at the school had expanded to two teachers. The school started with municipality’s multi-purpose hall which residents converted for its current purpose. Two buildings will be added this year. One funded by the Ayala Foundation is currently under construction. Another is being funded by the Provincial Governor of Palawan.

| First classroom | First graduation |

|

|

Continued development of the island and the rest of the municipality hinges on the availability of reliable and regular transportation to the rest of the country, especially the province of Palawan. This would facilitate the transport of goods and materials to the islands, and promote socio-economic activity — whose development has thus far been painfully slow.

Pag-asa Island is one of only two islands in the Spratly Islands with a functional airstrip. The Armed Forces of the Philippines constructed the Pag-asa airfield in the early 70’s and named if after the visionary PAF Commanding General that ordered its construction: Jose Rancudo. To date, however, there are no scheduled commercial flights to the municipal seat of power, save for periodic flights by AFP aircraft (the runway can accommodate the C-130 Hercules cargo planes and host of smaller aircraft). Charter flights have reached the island in the recent past. But with costs of reportedly P100K per charter, this would be too cost-prohibitive for local residents.

The primary means by which settlers travel to and from the closest Philippine landmass — Palawan — is by sea. Up until recently, passage to the island primarily by way of Philippine Navy ships. Civilians would be taken aboard as passengers on navy warships which re-supplied the various garrisons on Philippine-held islands. The Municipality expanded the community’s transportation options by acquiring its own vessel: the 40-meter M/V Queen Seagull.

Ship-to-shore transfers however are difficult because of the absence of port facilities. During the monsoon season, vessels have to drop anchor approximately 5 kilometers to the east to a submerged reef that provides comparatively better shelter than the waters around Pag-asa itself. This deficiency also means that the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) and Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) are unable to station patrol craft in the area to enforce environmental protection and similar laws. As had been reported on numerous occasions in the Philippine press, poachers are able to wreck havoc on the coral reefs within sight of Pag-asa authorities who were powerless to take appropriate action. The Philippine Navy is similarly unable to pre-position vessels for sovereignty patrols. The nearest naval station with a functional pier is in Ulungan Bay in Palawan which is over 500 kilometers to the east of the island.

For this reason, the Municipality of Kalayaan proposed the the Kalayaan Sheltered Port project. The Municipal government used the following graphic in one of their presentations to various national government agencies. It shows the location of the proposed port as well as the rehabilitated runway.

|

The timeline

The following table chronicles the twists and turns that this project has taken. Efforts to create a port have been initiated in the past. However this article will focus on the most recent project. Updates will be posted as new information becomes available . . . both current and historical.

| Date | Description | Relevant documents | ||

| June 22, 2011 | Upon advice of the Philippine Ports Authority, the Office of the Municipal Mayor brought its appeal for funds to build port facilities on Pag-asa to the Office of the President. The letter suggested tapping into Malampaya proceeds for the project. |   |

||

| July 5, 2011 | Office of the President referred the matter of the port facilities to Secretary of the Department of Agriculture (DA) for appropriate action. Note the inclusion of a patrol craft in the request, which was not mentioned in the initial correspondence in June.The rationale for why the request was routed to the DA instead of the Department of Transportation and Communication (DOTC), which has oversight over the Philippine Ports Authority, is unclear. |  |

||

| July 19, 2011 | Department of Agriculture acknowledged receipt of correspondence from Office of the President and indicates that the matter has been referred to Director of the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) |  |

||

| August 4, 2011 | Office of the Municipal Mayor sends a letter to the Department of Transportation and Communications appealing for assistance to build port facilities on Pag-asa Island. This line-of-communication is separate from the one that eventually went to the Department of Agriculture. |  |

||

| August 10, 2011 | The BFAR asks the Municipality of Kalayaan to submit a formal project proposal that includes designs and drawings of the proposed port as well as technical specifications for the requested patrol craft. |  |

||

| August 19, 2011 | DOTC informs Kalayaan Municipal government that the Kalayaan Shelter Port has been included in the DOTC infrastructure program for Calendar Year 2012. The letter, however, notes that continued action on the request hinged on Congressional deliberation and availability of funds.The Kalayaan port is included in the National Expenditure Program (NEP) for 2012. See here. An excerpt of the relevant section of the document appears to the right of the aforementioned letter. |   |

||

| December 15, 2011 | Office of the President signs Republic Act 10155, General Appropriations Act of 2012, into law. This budget allocated the sum of P5M to the development of two ports on Palawan, to include the port in Pag-asa, in accordance with the DOTC proposal for the NEP. See page 3 of this Department of Budget and Management (DBM) document. Relevant excerpt appears on the right.As per DBM guidance, funds allocated in this budget are only available until December 31, 2013. See here. |  |

||

| February 2, 2012 | Municipal government sends message to BFAR, amending original request to exclude patrol craft and focus instead on port facilities.Photographs and graphic representations of the proposed facilities, as well as a photo what the Vietnamese had done on Pugad Island, were included |   |

||

| March 28, 2012 | Kalayaan Municipal government responds, via email, to an urgent request from the DOTC for information about the scope of work, and specifications of the port.The response mentions a conference between the Philippine Ports Authority and the Flag-Officer-In-Command (FOIC) of the Philippine Navy on March 21, 2012 where both parties agreed to pool their resources to construct the port. Both agencies put forth their respective proposals. The Municipal government expressed preference for the Philippine Navy proposal.The Municipal office, admitting to a lack of expertise, referred the DOTC to the aforementioned agencies for the technical details. |  |

||

| March 30, 2012 | DOTC requests that the Kalayaan Municipal government present a thorough feasibility study of the project, that included justification for the project (e.g., technical, social, financial, and economic aspects), as well as details designs of the proposed port.The email indicates that this information is part of budget planning for 2013. However, the Pag-asa port project is not included in the DOTC section of the National Expenditure Program for 2013 (see here). Funds allocated in the 2012 budget, however, remain valid till the end of 2013. |  |

||

| August 30, 2012 | DOTC requested the Municipality of Kalayaan for information about previous studies conducted by the PPA/DA or the AFP about the feasibility of constructing a port. This data will reportedly be use for the drafting of a Term of Reference (TOR) for hiring of consultants for the drafting of a Master Plan for the project. |  |

||

| July 17, 2013 | In response to an update request from the Municipality of Kalayaan, the regional DOTC office relates that an un-named Under Secretary sought information about the purpose of the port — seemingly oblivious to the discussions between the municipality and various national government entities over the past three years |  |

||

| July 17, 2013 | Office of the Municipal Mayor of Kalayaan sent the following exasperated response to the latest information request from the DOTC |   |

||

| December 8, 2013 | Office of the Municipal Mayor of Kalayaan sought the assistance of Congressman Teddy Brawner Baguilat (Lone district of Ifugao), one of the members of a congressional delegation that visited Pag-asa island in 2011, to push for the realization of the port project. |  |

||

| March 12, 2014 | Representatives Rufus B. Rodriguez and Maximo B. Rodriguez Jr introduced House Bill 4167, which states the following:”The amount of One Billion Pesos (P1,000,000,000) is hereby appropriated to be exclusively used for the fortification and improvement of current structures present in the Kalayaan Group of Islands. Further, the same amount shall also be used to build new structures in the island like harbors, berthing facilities and other structures necessary to promote tourism in the islands and increase the defensive capabilities of the Philippines to strengthen the Philippines’ claim over it” |   |

||

| May 5, 2014 | As per the House of Representatives legislative database, House Bill 4167 was referred to the Committee on Appropriations | |||

| October 3, 2014 | Inquirer.net quoted Secretary of National Defense as follows:

The municipality has yet to issue an official statement in light of this policy declaration. |

Other references

RP’s remotest town freed from isolation, Manila Bulletin, June 15, 2005; copy retrieved from Timawa.net June 16, 2013

The promise of Pag-asa, Manila Standard, August 22, 2005; copy retrieved from Timawa.net June 16, 2013

Smart maintains GSM service on Pag-asa Is., Philippine Star, July 30, 2011; retrieved from Timawa.net on June 16, 2013

Chinese fishing fleet closes in on Pag-asa Island, Philippine Daily Inquirer, July 26, 2012; retrieved June 16, 2013

China reclamation projects a blatant disregard of DOC, ABS-CBN news, June 6, 2014; retrieved October 8, 2014

China advances Johnson Reef construction, IHS Jane’s 360, September 19, 2014; retrieved October 8, 2014

Licensed manufacture: The key to survival for SRDP companies?

Sunday , 13, July 2014 Self-Reliant Defense Posture Leave a commentIn the wake of efforts by the Senate Committee on National Defense to amend Section 53 of the Government Procurement Reform Act to give the President the power to negotiate modernization-related acquisitions (see here), supporters of local defense industry players sought to campaign the Office of the President to use that power to instruct the DND to buy from local defense manufacturers.

But with only two years remaining in the Aquino administration, such a move would be the kiss-of-death for the object of such a blatant act of patronage. Any such selection would, in essence, be a political decision thus firmly associating that company with the outgoing administration. This in turn gives the succeeding administration a very strong incentive to overturn the decision — if only to show the country that Malacanang was under new management.

Given the state of the local defense industry, virtually all players are vulnerable to the following two excuses for reversing the “anointment” of a preferred supplier:

- Qualification for suppliers. Normal bid invitations include a protection against fly-by-night suppliers that stipulate that “bidders should have completed, within five (5) years from the date of submission of bids, a contract similar to the project. With all Philippine defense companies still in an embryonic state, this virtually disqualifies all local players

- Commoditized products. Unless the preferred company were manufacturing the world’s only light saber — it really wouldn’t take much for spin doctors to question the selection. Regardless of the technical merits of company’s design, there are virtually no locally produced defense articles that are sufficiently unique to merit being singled out for a negotiated purchase, in lieu of other potentially cheaper imported alternatives

Even if a new administration upholds the previous President’s decision, these violations would still give SIGNIFICANT fodder for any political operator who wants to stir controversy. The company that benefited from presidential selection could then be in the unenviable position of becoming a tool for political leverage, or worse . . . impeachment.

Dealing with SRDP barriers

To deal with these omnipresent barriers to SRDP, defense companies could lobby for a change in the rules-of-the-game. The industry could ask Congress to amend procurement rules and make them more favorable to local production. This, however, is a time consuming approach with an uncertain outcome. Furthermore, such amendments have the potential for unintentionally weakening the protections that the current law was meant to implement in other procurement areas (e.g., routine purchases for schools, hospitals, etc.)

This is NOT the only option for the defense industry.

Despite the challenges presented in both the previous (RA 7898) and current (RA 10349) AFP modernization law cited earlier in this article, both actually contain substantial pro-SRDP provisions namely the following:

Sec. 10. Self-Reliant Defense Posture Program. — (a) In implementing the modernization program, the AFP shall, as far as practicable, give preference to Filipino contractors and suppliers or to foreign contractors or suppliers willing and able to locate a substantial portion of, if not the entire, production process of the term(s) involved, within the Philippines.

(b) In order to reduce foreign exchange outflow, generate local employment opportunities and enhance technology transfer to the Philippines, the Secretary of National Defense shall, as far as feasible, incorporate in each contract/agreement special foreign exchange reduction schemes such as countertrade, in country manufacture, co-production , or other innovative arrangements or combinations thereof.

(c) The AFP likewise ensure that in negotiating all applicable contracts or agreements, provisions are incorporated respecting the transfer to the AFP of the principal technology involved as well as the training of AFP personnel to operate and maintain such equipment or technology.

The spirit of the law is clearly in favor of SRDP. But the AFP modernization law does not actually direct the AFP to buy locally. It merely encourages it to do so, and with a very ambiguous caveat: “as far as practicable”. Given the state of the manufacturing industry, there is a significant disconnect between the intent of that section and practical implementation. The law does not lay out a plan for how to develop local defense industries to the point where it would be practical to source equipment from them. Prototypes should not be mistakenly equated with a production-ready design, or production capacity.

These two mandates: “buy local” and “buy only mature products” appear totally contradictory. After all, how can the AFP buy mature products from an immature local defense industry? A potential answer: license-production of existing weapon systems in the Philippines.

What is licensed manufacture?

The following is an excerpt of a document prepared by an organization that monitors the growth of the international arms industry.

Licensed production is where a company’s product is manufactured under contract by a company in another country. At its simplest, parts purchased from the vendor are assembled in the buyer country; at its most advanced, a weapon’s design, along with the expertise of engineers, is purchased and the equipment built in its entirety in the buyer country.

The document above cites India as an example of a country that insists on licensed production of weapons as a pre-condition for acquiring them from foreign vendors. Russia, Israel, France, and the United Kingdom have all complied with India’s demands to secure that regional power’s business. It is worth noting that India’s procurement policy is the same model espoused by Section 10 of the AFP modernization law. Other countries have adopted a similar approach.

Tim Huxley described in his book Defending the Lion City how Singapore uses a point-system for selecting weapon systems, with contracts awarded to options garnering the highest score. Special additional points are awarded to prospective suppliers that include locally-produced content thus ensuring success for companies that enter into partnerships with Singaporean companies. This strategy has resulted in in-country production of components for Singaporean F-16 multi-role fighters and CH-47 Chinook heavy lift helicopters.

The South Korean aerospace industry benefited greatly from licensed production of 120 KF-16 multi-role fighters. The US Department of Defense notified Congress of the South Korean request for local production in 1991, and a mere ten years later, the first South Korean supersonic aircraft, the T-50 Golden Eagle, took to the air. It was arguably no accident that the Golden Eagle was developed in partnership with Lockheed Martin, the manufacturer of the F-16 from which South Korea obtained the production license.

Incentive to license

The existing legislative framework offers local defense companies a host of under-utilized tools. In addition to Section 10 of the AFP Modernization Law shared above, prospective SRDP entrants also have Republic Act 5183 working in their favor. This law prohibits the Philippine government from sourcing items from companies that aren’t majority Filipino owned. This means that any foreign vendor seeking to sell its wares to the AFP needs to establish arrangements with Philippine business entities, which will then be responsible for representing the vendor in public biddings and similar engagements.

The following partnerships have been outcomes of this representation requirement

| Philippine company | Foreign companies represented | Acquisition project | ||

| Aeromart Commercial & Industrial Corp | Marsh Aviation (USA) | Service Life Extension Program (SLEP) for OV-10 Bronco aircraft | ||

| Aerotech Industries Philippines | Alenia (Italy) | Supply SF-260 training aircraft for the Philippine Air Force | ||

| Firepower Defense Contractors | Rheinmetal Denel Munition Pty Ltd (Germany) Denell Pty Ltd (South Africa) Companhia Brasilera de Cartuchos (Brazil) |

Supply of various small arms munitions for the Philippine Army and general purpose bombs for the Philippine Air Force | ||

| Urban Industrial Corporation | Arcus Co. (Bulgaria) Kompanija Sloboda A.D. (Serbia) |

Supply of 40mm grenade launcher ammunition and artillery rounds for the Philippine Army |

This law virtually ensures that a Filipino company will be involved in any acquisition — with the exception of government-to-government deals. While the companies that have thus far emerged have been mere middle-men that lacked manufacturing capacity, Philippine defense companies could potentially use this law as a catalyst for licensing talks, thus forging an enduring production partnership instead of just a representation relationship.

Arguably, this law was meant to entice manufacturing investments to the Philippines. Having defense industry players leveraging the law for licensed production would use the law the way it was intended.

This approach has the following advantages:

1. Existing laws can be used without any changes. This means that this course of action is available today

2. There would be no need to curry political patronage since this simply requires the law to work as written and intended. Although ensuring DND buy-in of the concept would still be necessary, as would an SRDP roadmap.

3. The two-countries rule AND the minimum requirement for deal sizes are both satisfied since the Philippine company would leverage those characteristics of their foreign partner

Once this joint venture is established, and wins bids for AFP contracts, the Philippine company would then be completely justified in claiming to have had experience with sizeable government contracts, thus satisfying the minimum deal-size requirement. A status that it could not have achieved on its own. Furthermore, the company could leverage its status as a licensed manufacturer of an established company to sell its own products both domestically and overseas.

Plan of action

How could this all play out? Ultimately that would depend on the nature of the equipment that will be manufactured, the capacity of the Philippine company (which would determine the capital expenditure required), the requirements of the foreign entity, and the export controls of the foreign company’s country of origin.

Philippine companies may also have to come to grips with the fact that they can’t advance on their own and may need to form a consortium of companies with complementary capabilities. This would potentially cut down on capital expenditures, since the consortium would take advantage of the investments already made in equipment and production space, and enhance the resulting entity’s competitiveness as well as credibility as manufacturing partner.

The following simplistic plan of action should, at a high-level, should cover the process in broad strokes:

1. Select a foreign manufacturer whose products are already in use by at least two foreign countries — or at least the country of origin. This would satisfy the requirements of the AFP Modernization Law

2. Enter into a representation agreement with this manufacturer in accordance with RA 5183

3. Enter into a licensing agreement with this manufacturer to have THEIR products manufactured at the Philippine company / consortium’s manufacturing facilities

4. Take part in a bid invitation, and submit a bid that reflects the savings made possible by local manufacture

Conclusion

Instead of leveraging their design portfolios, local defense companies should consider to looking to their manufacturing prowess instead, and enter into licensing arrangements with existing players. This approach would not only allow it to tap into the admittedly small Philippine defense market, it could also launch it into the world stage, where the bulk of the defense dollars are to be sourced anyway.

———-

Author’s note: This article is based on the opening message of what eventually became a productive, well-received, email conversation with the founder of a prominent player in the Philippine defense industry. Details of that discussion are being kept private as per request. But the substance of the proposal is shared here.

This post was also posted on the Timawa.net forum here.

ERRATA: The following bullet point was removed from the main article because the IRR of the AFP Modernization law actually exempts local companies from this rule: Section 1 of the revised AFP Modernization Law re-affirmed Section 4 sub-paragraph b of the original modernization law, RA 7898, that explicitly stipulated that “no major equipment and weapon system shall be purchased if the same are not being used by the armed forces in the country of origin or used by the armed forces of at least two countries”. This is pretty much a deal breaker for patronage-based SRDP. Any administration looking to establish its anti-corruption credentials could very easily resort to reversing the “hand-out” for a quick win.