Philippine Defense Today (Adroth.ph)

In Defense of the Republic of the PhilippinesNavy 2012 drydock cycle begins

Friday , 6, January 2012 BRP Artemio Ricarte (PS-37), BRP Magat Salamat (PS-20), BRP Pangasinan (PS-31), Philippine Navy Leave a commentThe Philippine Navy drydock cycle for 2012 started on the first week of January as the service published P49M worth of bid invitations.

| Ship | Authorized Budget for Contract | Details | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| BRP Magat Salamat (PS 20) | PHP 24,500,000.00 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| BRP Artemio Ricarte (PS 37) | PHP 9,500,000.00 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| BRP Pangasinan (PS31) | PHP 15,000,000.00 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PHP 49,000,000.00 |

BRP Artemio Ricarte (PS-37) is a Jacinto class Offshore Patrol Vessel. She and her sisterships are ex-Royal Navy boats that used to be part of the British Hong Kong squadron before the colony’s return to China. For discussions and photos of this ship, see here.

BRP Pangasinan (PS-31) and BRP Magat Salamat (PS-20) are WWII vintage, ex US Navy Patrol Craft Escorts. For photos and discussions about PS-31, see here and here for PS20.

To protect the AFP against accepting unsupportable surplus equipment, Administrative Order 169, series of 2007 stipulated the following acceptance criteria.

3.2.3. Used equipment or weapons system may be acquired, provided that:

a. The used equipment: or weapon system meets the desired operational requirements of the AFP;

b. It still has at least fifteen (15) years service life, or at ieast fifty percent (50%) of its service life remaining, or if subjected to a life extension program, is upgradeable to attain its original characteristics or capabilities;

c. Its acquisition cost is reasonable compared to the cost of new equipment; and

d. Tbe supplier should ensure the availability of after-sales maintenance support and services,

To download a copy of this Administrative Order, click here.

Updated assessments of F-16 airframe life

Thursday , 29, December 2011 Philippine Air Force Leave a commentAt the turn of the 21st Century, as the USAF found conducting combat operations over Iraq and Afghanistan with increasingly aging aircraft that were leftovers from the Cold War it took stock of its aircraft inventory and came to the following observation

http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/aircraft/f-16-life.htm

As a system’s cumulative operating time increases, the probability of its failure tends to increase, decreasing the system’s potential reliability. Reliability also decreases when the conditions under which the system was designed to operate change. Many of these aircraft are at critical points in their life cycles. For example, by 2001 many F-16s had reached 2,400 hours flying time, a significant point in an 8,000-hour service life. As these aircraft age and operating conditions changed, the reliability of systems and components decreases, and failures occur more often, which increased maintenance costs. Increased failures affect aircraft maintainability, requiring more maintenance and often increasing repair times when more hard breaks occur. In the case of the F-16, operational usage had been more severe than design usage (eight times more), resulting in the acceleration of its airframe service life at a rate that may not let it reach its expected overall service life.

Also at this point in history, the fate of its next generation stealth combat aircraft, the F-22 and F-35, hung in the balance. It, therefore, became politically expedient to highlight pessimistic projections about the future prospects of the USAF F-16 fleet.

Fast forward to the present day. The F-22 production line is complete, but with fewer aircraft than originally projected. F-35 development is moving ahead, but slowly. Faced with the prospect of reduced capability as a result of the latter aircraft’s delays, the USAF re-evaluated it fleet again, and came to the following conclusions which were published in Aviation Week magazine.

< Edited >

However, the U.S. Air Force, which operates more than 1,000 F-16s of varying blocks, has no plans to procure more F-16s. Rather, the service is exploring options to extend the life of its fleet until the F-35 is introduced into service in enough numbers to handle the suppression and destruction of enemy air defense roles.

Originally designed for 4,500 flying hours, a previous upgrade extended the lifespan to 8,000 hr. But after conducting a monitoring program on the fleet, Air Force officials have found that they are flying the aircraft 15-20% “less hard” than planned, meaning pilots are not flying the jets to their maximum limits regarding such elements as speed or g-forces. This is partly because in the decade since the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the F-16s have been used largely to support ground forces or patrol the skies in permissive airspace, missions that do not require the taxing maneuvers seen while operating in hostile environments, says Maj. Luther Cross, F-16 program element monitor for Air Combat Command.

This has prompted the Air Force to calculate what officials call equivalent flying hours for each airframe, just as they do actual flying hours. Using the equivalent-hour metric, service officials are able to estimate the projected life, taking into account lighter use of the fleet in recent years, says Cross. This practice is also being applied to other fleets in the service.

This alone adds “several years” of life to each aircraft, he says. Still, the Air Force is considering a structural service life extension program (SLEP) to the newest Block 40/50 F-16s, with a 12,000-hr. goal per airframe.

The prospects for the availablity of suitable aircraft for the PAF’s needs, therefore, are not as bleak as the earlier GlobalSecurity.org would have pictured.

This article was also published on the following FaceBook group: F-16s for the Philippine Air Force

To discuss the article shared above, see the following Timawa.net discussion.

Government Arsenal expands product line

Saturday , 24, December 2011 Self-Reliant Defense Posture Leave a commentThe Government Arsenal announced via its Facebook account, and through Timawa.net, its plans to expand its product with the following rounds for 2012. The following photographs show the new cartridges.

|

|

|

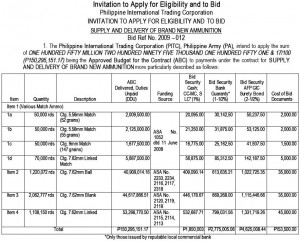

The match-grade rounds for 7.62mm and 5.56mm are of particular interest. These are to be manufactured for the Philippine Army ASEAN Armies Rifle Meet shooting team and Philippine Marine Scout Snipers respectively and would minimize, if not eliminate, future need for bid invitations like the following.

|

PG-118 and PG-390 rescue cargo vessel

Saturday , 24, December 2011 Andrada class patrol gunboats, BRP Jose Loor (PG-390), Philippine Navy, Ships, Tomas Batillo class Leave a commentTwo Philippine Navy vessels on search retrieval operations for Typhoon Sendong victims rescued a cargo ship that caught fire off Misamis Oriental. Sun Star – Zamboanga reported that the fire broke out on the M/V Foxbat at 3:15 p.m. Thursday while it was anchored northwest of Lugait Point.

BRP Emilio Liwanag (PG-118), a Tomas Batillo class gun boat, and the BRP Jose Loor (PG-390), an Andrada class patrol boat, both responded to the M/V Foxbat’s distress call. The fire, which is believed to have been caused by faulty electrical wiring, was brought under control after 3 hours.

Preparing for F-16s: “Peace Carvin” in reverse

Friday , 23, December 2011 AFP modernization, Air Force, Philippine Air Force Leave a commentThe Office of the President, Department of Foreign Affairs, and the Philippine Air Force have all publicly declared the Aquino administration’s intention to acquire 12 surplus F-16C/D aircraft from the United States. These are interesting times for the Philippine Air Force, whose prevailing skill-sets are still geared towards equipment that is decades behind the Falcons.

It’s been six years since the PAF had operational fighters in its inventory. Its last F-5A Freedom Fighters, which were day-time-only interceptors, were decommissioned in 2005. Over two decades had passed since it operated true all-weather fighters — its F-8 Crusaders. The 60’s era Crusaders proved to be a handful for the PAF (see the following Timawa discussion for details), and by the late 80s were relegated to a grass field at Clark field, where ash fall from Mt. Pinatubo eventually sealed their fate. While the handful of S211s allows the service to maintain a modicum of competency in jet-aircraft operations, the PAF Air Defense Wing is a shadow what it once was when its aircraft intercepted Soviet bombers in the South China Sea.

If we are to keep the hoped-for F-16s from becoming hangar queens, or become the latest recipient of the Philippine media’s favorite moniker for PAF aircraft: “flying coffin”, its ability to operate aircraft at this level of sophistication must be elevated without delay.

The following is a summary of a Timawa.net discussion that seeks a way to fast-track the upgrade of PAF skills . . . should the request for these aircraft be granted.

How does this exercise seek to accomplish its mission statement and objective?

Learning by example

When Singapore replaced their Hawker Hunters with F-16A/Bs in 1987, they opted to have them delivered to Luke AFB AZ instead of direct to Singapore. Thus the first incarnation of Operation: Peace Carvin began. For two years, from 1987 to 1989, the USAF trained 100 RSAF pilots and maintenance personnel to operate and maintain their new birds. Subsequent Peace Carvins trained additional personnel in F-16C/D aircraft and more recently the F-15SG.

These Singaporean operations can be broken down into the following elements:

Aircraft – the RSAF stationed as many as 12 aircraft at the air base as training platforms

Trainees – these are the 150 Singaporean personnel, including 15 pilots, are that undergo training at the base. These personnel and their families live on-base for the duration of the training cycle

Trainors – these are USAF personnel that are seconded to the RSAF and have operational control of the unit. Personnel management, however, remains with RSAF officers

Budget – Singapore was responsible for the following items:

• Salaries of all personnel involved, to include USAF personnel

• Maintenance and operations expenses

• Ordnance

This training arrangement afforded Singapore access to the full range of training facilities that the USAF established for its own pilots (e.g., bombing ranges, etc.) and maintenance crews (e.g., AFTOs, training mockups). Although the US and Singaporean governments refuse to publicly declare the annual cost of the program, it would arguably be safe to assume that it would be prohibitive.

While some overseas training will be required for the initial batch of pilots and maintenance crews for the planned F-16s, what if alternative arrangements could be made to permit training in advance of MRF delivery?

Peace Carvin in reverse

This proposal seeks to gain the benefits of Peace Carvin, but without the attendant costs.

Key elements of this proposal:

• Task force

• Use of subject matter experts

• Training opportunities

While there is no avoiding sending PAF personnel overseas for training, why not work to build-up in-country training capabilities in preparation of the arrival of aircraft? Training, therefore, can begin well in advance of the actually transfer of equipment.

The “reverse” in this proposal is that foreign training resources are brought to the Philippines, where training can be done all year, instead of sending personnel overseas for a few months at potentially great expense. It will not, however, preclude overseas training opportunities.

Task force

PAF HQ, ADW, and AETC will establish a task force to identify skills gaps related to operating aircraft at the F-16 complexity level, and develop both fast-tracked and long-term training programs to address these gaps. This task force will function as a training directorate that will have overall responsibility for the program.

The mission statement for the effort:

“Create a maintenance, operations, and logistical culture that is conducive to effective, efficient, sustainable use of 4th Generation combat aircraft”

These training programs will be conducted in the Philippines.

Use of subject matter experts

The task force will be empowered to retain the services of subject matter experts who will be responsible for administering key aspects of training programs either as a whole or in part.

These subject matter experts can be:

• Technical advisers seconded or assigned to the Philippines by a foreign country

• Private contractors

• A combination of both

Subject matter experts will be responsible for the following in their respective areas of concern:

• Familiarize PAF personnel with relevant AFTOs or their equivalent

• Impart best-practice information and techniques

• Aid in forecasting

When selecting contractors, preference will be given to entities that are willing to lease key maintenance and/or training equipment, that are relevant for their training programs, to the PAF using a BOT scheme. Contractors can include companies such as Sikorsky Aircraft Services or be entirely new companies that are setup as Public-Private Partnerships.

Whenever practical, the BOT scheme will be used to acquire support and training equipment (e.g., APUs, simulators, training mock-ups, etc.)

Training opportunities

This is the “core” of the reversal concept.

To provide practical learning opportunities for prospective PAF F-16 crews, the task force, in cooperation with the Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT) board and the DFA, will work to establish high-frequency exercises with foreign armed forces that operate F-16s.

Having operational F-16 units in-country will provide PAF personnel, who complete pre-requisite training modules designed by the task force, the opportunity to apply theoretical knowledge, and acquire practical best practices information from experienced air crews.

Small-scale, temporary, basing of foreign assets is preferable. Forward-basing for the receptive foreign country results in a training opportunity for the PAF.

The task force will have a hand in selecting personnel who will be sent to the US for training on F-16 maintenance and operations. These personnel will be selected not only for their qualifications, but also for their ability to serve as mentors / team leaders who will then form the leadership foundation for a new jet-qualified work-force.

Other interim training opportunities

Indonesia reportedly takes up a significant amount of Singapore’s simulator resources (see here). Could a similar arrangement be setup with our non-US allies? South Korea perhaps?

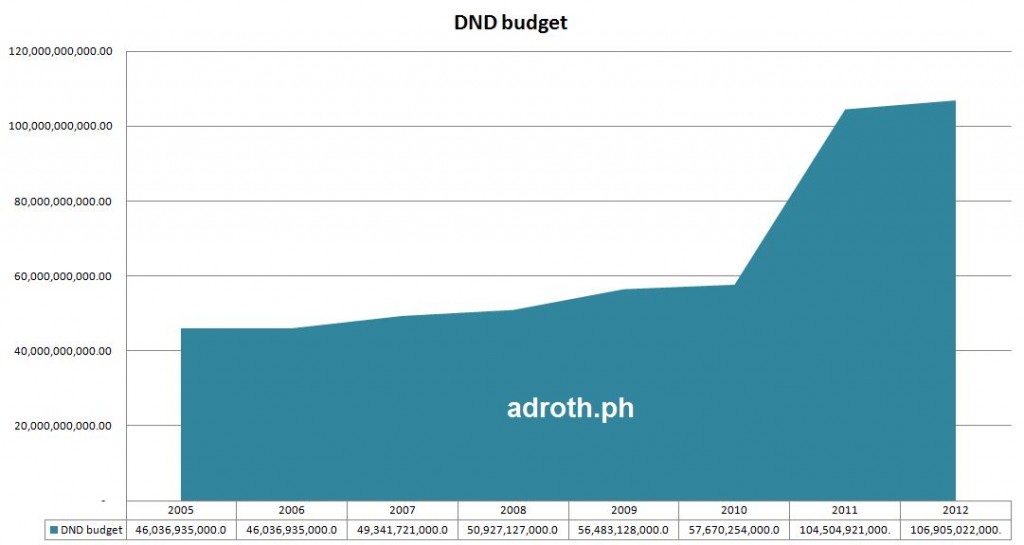

President Aquino signed the P1.816 Trillion 2012 national budget on December 15. Based on details revealed in the Manila Bulletin, the DND allocation was P108.1B. This represents a P1.35B increase from the Department of Budget and Management’s (DBM) 2012 National Expenditure Program which originally sought P106,750,022,000. This amount is P3.6B, or 3.4%, higher than the 2011 budget.

As of writing, the 2012 General Appropriations Act is not yet available on the DBM Website. For discussions about this budget, see the following Timawa.net discussion.

|

Navy Q4 2011 drydock-season

Saturday , 10, December 2011 BRP Abraham Campo (PG-396), BRP Ismael Lomibao (PG-383), BRP Lake Taal (AF-72), Drydock 2011, ex-USCG Point class, ex-USN YOG Leave a commentThe Philippine Navy has P33M worth of drydocking contracts up for grabs in the 4th quarter of 2011. The following two patrol gun boats and tanker are due for maintenance. All bids are due to close on December 20, 2011.

| Ship | Authorized Budget for Contract (ABC) | Details | ||||||||||||

| BRP Ismael Lumibao (PG-383) | P7,500,000 |

|

||||||||||||

| BRP Abraham Campo (PG-396) | P7,500,000 |

|

||||||||||||

| BRP Lake Taal (AF-72) | P18,000,000 |

|

BRP Ismael Lumibao is an Andrada Class patrol boat and was the 13th craft in this class of 22 boats. It was delivered to the Philippine Navy on February 1, 1995. For photographs and additional discussion about this boat, see the following Timawa.net thread.

BRP Abraham Campo is one of two ex-USCG 82-foot Point Class cutter and entered Philippine service on March 3, 2001. For photographs and additional discussion about this boat, see the following Timawa.net thread.

BRP Lake Taal is an ex-US Navy gasoline tanker that entered Philippine Navy service in March 5, 1980. For photographs and discussions about this ship, see the following Timawa.net thread.

Is Congress turning back the Capability Upgrade Program (CUP) clock?

Thursday , 8, December 2011 AFP modernization, DND-AFP budget Leave a commentThe Capability Upgrade Program is a priority component of the Philippine Defense Reform (PDR) that sought to re-prioritize the AFP modernization program . It consists of three six-year phases designed to bring the AFP to a condition where it could be modernized, before it actually pours funds into modernization.

| Phase 1: Back to basics | This phase sought to apply the sum of P5 billion per year, for a total of P30 billion, to upgrade the AFP’s Internal Security Operations (ISO) capabilities in the following key areas:

Understandably, ground troops benefited the most from this phase, thus giving the lion’s share of funding to the Philippine Army and Philippine Marines. The Philippine Air Force and Philippine Navy also received funding, but primarily for acquisitions that improved their ability to support land forces. |

|

| Phase 2: Transition from basic capabilities to first-level modernization | This phase sought to invest P10 billion a year, for a total of P60 billion over six years, to begin meeting basic requirements for external security threats. This phase would have focused on the needs of the Philippine Air Force and the Philippine Navy. | |

| Phase 3: Beginning of real modernization | This final six-year phase sought to apply P20B per year to complete the AFP’s goals for its 18-year capability planning horizon. |

According to the AFP Modernization report of 2008, Phase 1 started in 2005. Among the highlights of the phase were:

- Mobility

- 1/4 ton KM-450 trucks

- KM-250 trucks (6×6)

- ACV-300 and ARV armored vehicles

- Refurbishment of F-27 transport aircraft

- UH-1 light transport helicopters

- SF-260 trainer aircraft

- Multi-Purpose Assault Craft (MPAC)

- Firepower

- Squad Automatic Weapons: M249 (Belgium) and K-3 (South Korea)

- Night-fighting systems (PA, PMC)

- Jacinto Class Patrol vessel upgrades (Phases 1, 2, & 3)

- PKM patrol gun boat acquisition and upgrade (South Korea)

- Communication

- Harris digital radios

- Base communications network

- GPS units for infantry units

- Force protection

- PASGT-type Kevlar helmets

- Level 3 body armor

- Combat life support for individual units

- Medical equipment for AFP hospitals

A more comprehensive list is available on the Timawa.net forum here.

The primacy that ground forces enjoyed is readily apparent. While the Philippine Navy and Air Force also received their share of funds, the projects prioritized were assets that supported ground forces. The Navy’s acquisitions since enactment of the Modernization Law consisted of logistical support vessels and patrol craft optimized for littoral operations. The Philippine Air Force became, for the most part, a transport helicopter force, as air defense considerations were set aside with the retirement of its last F-5A fighters in 2005.

While some critics labelled the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) the weakest military force in Asia. Other, more astute defense observers, called it “the most COIN-specialized force in Asia”.

By the turn of the second decade of the 21st century, things were looking up. By 2011, the programmed end of the ISO phase, all CUP Phase 1 acquisitions were complete. Thus the AFP was poised to begin the transition to Phase 2, and develop capabilities that could be applied to external defense concerns such as the Kalayaan Island Group. The Philippine Navy and Philippine Air Force were to get their due.

The legislature, however, appears to be oblivious to the the progress already made since 2005. The two most comprehensive AFP Modernization bills currently pending in Congress, the Enrile (SB 2093) and Lacson (SB 2938) bills, are both adamant that ISO remain the principal focus of the AFP Modernization program. The Lacson bill even seeks to return the program to how it was in Phase 1 of the CUP, by requiring that:

“. . . the first five (5) years of the implementation of the program shall be substantially focused and directed initially towards addressing the internal security threats of the country . . .”

The Enrile bill inserted the following into the law’s objectives:

“To develop its capability to detect, prevent, neutralize and repel internal threats against the Filipino people, the government and its institutions.”

Do our political leaders really want to put off preparations for external defense for another half-decade . . . or more?

To comment on this essay, see the following Timawa forum discussion.

Philippine Defense Today is now on Google+

Thursday , 8, December 2011 About this blog Leave a commentPhilippine Defense Today (adroth.ph) is now on Google+. Visit: https://plus.google.com/112582633443812220718/posts